This is the first in a new series called “Better Know a Scientist”. The goal of these interviews will be for scientists to share their research, for us readers to gain more knowledge in a field we may not be familiar with, and to learn a bit about the individuals doing the research as well. I’m going to be interviewing my friend, Erfan Vafaie (@sixleggedaggie), who blogs at sixleggedaggie.com. Over the past few years, we’ve sent each other papers that we’ve found interesting, and I’ve asked him about bugs and GMOs to get his insights and perspectives. Like me, he is also an Iranian-Canadian, but lives in Texas.

Here we go! Continue reading “Better Know a Scientist: Entomologist Erfan Vafaie”

Tag: Bt

A new meta-analysis on the farm-level impacts of GMOs

Written by Jonas Kathage

Despite the fact that the global area of GM crops has grown rapidly over the past decade and now encompasses more than 170 million hectares it is still questioned whether current applications of genetic engineering in agriculture are beneficial to farmers or not. While several reviews and meta-analyses on the impact of GM crops exist, the evidence is still not regarded as conclusive by many. A new meta-analysis of the agronomic and economic impacts of GMOs has appeared in the journal PLOS ONE. It summarizes the findings of 147 original studies published until March 2014. Besides being the most up to date, this meta-analysis has two other features that make it an important addition to the existing body of meta-analyses and review articles: First, it includes not only studies from peer-reviewed journals but also those that are not (grey literature), thus providing a broader perspective. Second, the authors investigated the reasons why different studies found different results, providing several interesting insights. Continue reading “A new meta-analysis on the farm-level impacts of GMOs”

Sex and death in the cornfields, Part II- Why rootworms?

Written by Stephanie Gorski

Hi, I started this series to explain a little more background behind the news and opinion articles you may have seen about Bt-resistant corn rootworms, with scary titles like Voracious worm evolves to eat biotech corn engineered to kill it and Evolution one-ups genetic modification. I started out talking about the system as it was originally developed for moths, but I wanted to come back to talk about why rootworms are so good at developing resistance to Bt crops. Part I of this article talked about refuges and how they are used to slow insect resistance, so I’m assuming you know how a refuge works. If you don’t, check out Sex and death in the cornfields: What is a refuge?

There are several different pestiferous species of rootworms, but they are often lumped together because their larvae are difficult to tell apart. The Western corn rootworm (Diabrotica virgifera virgifera) is the most damaging and most studied.

As you may recall, transgenic Bt-expressing corn targeting rootworms has only been around since 2003, and there are already reports of resistance. Resistance has been confirmed in Iowa. Reduced susceptibility has been reported in Colorado, Minnesota, Nebraska, and South Dakota. (Reduced susceptibility is basically the same idea as resistance, but is defined more loosely; there is a lower standard of evidence to meet.) So it looks like there will be more resistance occurring in the near future.

It looks like we haven’t been as effective in slowing resistance development with rootworm-active transgenics as with moth-active transgenics. Why? There are lots of things about the rootworm system that make it less simple and less elegant than the moth system. Continue reading “Sex and death in the cornfields, Part II- Why rootworms?”

Sex and death in the cornfields: What is a refuge?

Written by Stephanie Gorski

A lot of people have sent me news articles about the spread of Bt-resistant corn rootworm because they know I am interested in transgenic Bt. These articles have alarming titles like Voracious worm evolves to eat biotech corn engineered to kill it and Evolution one-ups genetic modification. Yes, unfotunately, corn rootworm that are resistant to transgenic Bt corn are real (Cullen 2013, EPA 2014a). But the story is more complex than you’d think from these headlines. To explain, I’d like to talk about IRM (insect resistance management), specifically, the IRM for Bt corn targeting pest caterpillars (Lepidoptera). Please note that corn rootworms are not Lepidopterans, but Lepidopterans are a good model for understanding how IRM works. Continue reading “Sex and death in the cornfields: What is a refuge?”

How does the BT protein work?

Life, at its most basic level, is really just a series of chemical reactions. Biochemists and molecular biologists, such as myself, look at how life works at the very most basic level. Unfortunately, this stuff is all very complicated and there are few resources online to explain how this work.

Anastasia has a wonderful post about how Bt corn works in transformed plants, titled simply ‘Bt‘. In the post, she focuses on how the protein works from the angle of a plant biologist. In this post, I will discuss the protein from the angle of an entomologist. Specifically, I will answer this question: What happens when a caterpillar eats the Bt protein?

Contrary to what a lot of people think, Bt is not unique because it’s from an insect pathogen or even because it’s inserted into a plant. Insect pathogens, namely viruses, fungi, bacteria and nematodes, have all been used in pest control operations. Insects which bore into plants are frequently controlled by pesticides which incorporate themselves into plants, like neonicotinoids which are applied as a seed treatment that gets transferred to the plant as it grows. This method isn’t unique to ‘conventional farming’ either, because organic growers will inject Bt into plants to control stem boring caterpillars. Besides, plants have their own insecticides which we consume whenever we eat food. Instead, Bt is unique because the toxins that we use from the bacteria are often only active against very specific groups of insects.

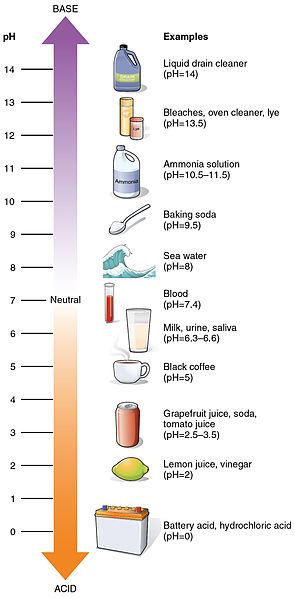

Some Bt proteins work on caterpillars, others work on beetles. All, however work on the gut of the insect. Although I’m not focusing on humans in this post, I would like to compare and contrast the environments of the gut pH between insect and human guts. In humans, the Bt protein is very quickly digested in vitro, and this is due in part to the fact that human and insect stomachs are very different.

Proteins are sensitive to environment, and one very important factor is the pH the protein is in. The pH of human stomach acid is about 2 while the pH of the insect gut is about 10. To give you an idea of how different these environments are, remember that prolonged contact with a highly acidic (pH 2) or a highly basic (pH 10) substance will damage human tissue, which is a pH of about 7. The tissue damage occurs because the local pH is really important for their function. If the pH isn’t within the proper range, the proteins unfold and won’t work. When this happens to human tissue, the result is a chemical burn. Most proteins have a relatively narrow pH window in which they’ll work, and Bt is no different.

Bt toxin requires a high (basic) pH to be active, and must be activated by specific protein-cutting-proteins in the insect gut. The Bt toxin is comprised of a bunch of smaller proteins that work together by teaming up to form holes in the membranes of the cells that form the gut. The holes that are formed are small, and allow salts and other small solutes to get in. When the salts rush in, water follows. When the water flows in, the cells burst. When enough cells burst, the midgut becomes full of large holes. At this point the gut contents spill into the body cavity of the insect, resulting in the death of the insect.

Earlier, I mentioned a wonderful post by Anastasia about the differences between the bacterial proteins and the ones put into corn. However, I do not view the protein encoded by transgenic crops as the toxin. Instead, I view the protein described by Anastasia as part of the toxin. Remember that this gene encodes a protein, and in the gut there are multiple identical copies (subunits) of this protein that hook together to create the pore that kills the caterpillar. This might seem like a pedantic distinction, but it’s very important to understanding how this protein works.

There are two main differences between the proteins found in bacteria and the proteins found in corn. The first is that in the bacterial proteins, there is an extra subunit that has been removed in the genes used in transgenic crops. The second is that one bacteria may produce multiple Bt protein subunits, whereas the corn only produces one subunit*. This is important because those different subunits may interact in different combinations with various potential effects on toxicity and specificity.

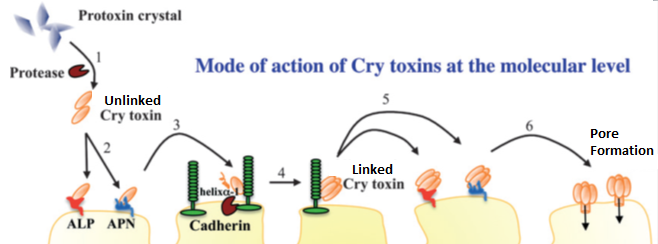

So far in this story, the caterpillar has somehow consumed the toxin and if we’re talking about a bacteria derived toxin, the Bt toxin has been activated by the caterpillar’s proteases by cutting off a very specific part from the ‘back’ or, C-terminus of the protein. What we’ve got now is a protein floating in the gut of the caterpillar. In the gut, the protein isn’t going to do a whole lot of damage. To do it’s damage, it has to get down to the cell membrane and latch onto some other proteins and get close to that membrane. Here, we introduce another cast of players:

- Alkaline Phosphatases. Many proteins are turned on and off by the addition of phosphate groups. Under the basic conditions found in the insect midgut, phosphate groups are removed from molecules by alkaline phosphatase. In mammals, the stomach lining is protected by a thick layer of mucus and the pH of this mucus is regulated in part by alkaline phosphatase. In addition, alkaline phosphatase in mammalian intestines have secondary functions which range from regulating the absorption of fat to regulating immune reactions during bacterial food poisoning to regulating interactions between our immune system and beneficial bacteria. Alkaline phosphatases have a lot of functions, many of which aren’t related to digestion.

- Aminopeptidases. Insects consume a variety of proteins in their diets, so digestion involves a lot of proteins that break down other proteins. A lot of these are floating around in the liquid of the guts, but others are attached to the intestinal cells. Some proteins simply cut proteins in random** fashion to speed up digestion by increasing surface area. Aminopeptidases degrade proteins from one end, the ‘front’ or N-terminus, of the protein.

- Cadherins. In mammals, these proteins, along with integrins, play a major role in holding cells together. In insects, they probably play a similar role.

Aminopeptidases, alkaline phosphatases, and cadherins are very common on the gut wall. While the Bt protein is floating in the gut, it eventually runs into aminopeptidases and alkaline phosphatases. Very briefly and very loosely, it binds to these molecules. This binding likely serves to hold the protein to the gut membrane until they run into a cadherin molecule. While the interactions are weak and temporary, eliminating the ability of Bt to bind to these proteins greatly decreases the toxicity of these proteins. The Bt protein eventually finds and binds tightly to a cadherin protein.

While bound to the cadherin protein, the shape of the protein changes in such a way that allows proteases in the gut to cut the protein in a very specific manner. The way this protein gets cut exposes hydrophobic amino acids on the protein. This more or less creates a sticky patch that allows the Bt protein to link up with other Bt protein subunits. After these subunits hook together, they loose their ability to bind to cadherin and then gain the ability to bind very strongly to gut-bound aminopeptidases and alkaline phosphatases. After binding to the aminopeptidases and the alkaline phosphatases, this group of Bt proteins then inserts itself into the cell membrane and forms a pore.

There are still a lot of unknowns about how Bt proteins work, and we’d really like to understand these proteins more so we can engineer new versions. We don’t quite understand what happens between the time the protein leaves the aminopeptidases and alkaline phosphatases and creates a pore in the cell membrane. There’s also some debate on how many subunits form one protein. These might seem like minor things, but even small advances in our understanding of exactly how this protein works goes a really long way in our ability to use these proteins. For example, B. thuringiensis can encode proteins of differing subunits that are toxic by themselves, but when combined together (Cry1Aa and Cry1Ac for gypsy moth larvae) will synergize each other and become more toxic than either protein alone. Eliminating certain parts of the protein may also change toxicity. If we could figure out how to do this in a predictable fashion, we could increase the number of proteins created by transgenic plants while simultaneously minimizing the number of genes we need to insert into the plant. It would also be possible to predict how insects will become resistant to Bt, and which modifications of the protein would allow us to overcome this resistance. This, in turn, would likely make the evolution of Bt pesticide resistance far more difficult for crop pests.

So there you have it…this is how Bt works. It’s a very complicated process, but when you understand some of the biochemical details it’s actually a lot less complicated than it would initially seem. We don’t know everything about how the protein works, but we do know enough to be able to use it. As we find out more about the protein, and figure out new ways to manipulate it, we can hone and sharpen this tool so that it will be useful for years to come.

*Stacked corn produces two different subunits which don’t bind together.

**Not exactly random – cuts are made after specific amino acids. This just serves to break the proteins into smaller chunks to increase the rate of digestion. So, for our intents and purposes it’s all random. It’s not really, but these are pedantic differences that don’t matter for this discussion.

Works Cited

- Harris T.J.C. & Tepass U. (2010). Adherens junctions: from molecules to morphogenesis, Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 11 (7) 502-514. DOI: 10.1038/nrm2927

- Lallès J.P. (2010). Intestinal alkaline phosphatase: multiple biological roles in maintenance of intestinal homeostasis and modulation by diet, Nutrition Reviews, 68 (6) 323-332. DOI: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00292.x

- Pardo-López L., Soberón M. & Bravo A. (2013). Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal three-domain Cry toxins: mode of action, insect resistance and consequences for crop protection, FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 37 (1) 3-22. DOI: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00341.x

Pest resistance to Bt crops

Written by Jonas Kathage

The issue of pest resistance to insect resistant Bt crops receives regular media attention, partly because anti-biotechnology lobbies use it as an argument to vilify GM crops. The German NGO testbiotech, in a recently published report commissioned by Member of the European Parliament Martin Häuslingof the Green Party, argues that because of potential resistance development, GM crops should not be allowed for cultivation in the EU:

There must be no large-scale, commercial cultivation of GE herbicide-tolerant or insecticide-producing crops. Such crop cultivation is unsustainable and will lead to a ‘race’ to step up their cultivation.

The idea that a particular technology should be banned if it cannot be used forever is dangerously misguided. Continue reading “Pest resistance to Bt crops”

Bt

There’s a lot of interesting and sometimes conflicting things about Bt out there. Most people know that the Bt gene originally came from Bacillus thuringiensis bacteria, which are common in soil, but there’s a lot more to know! Here, I’ll discuss the differences and similarities between Bt from bacteria and Bt which is found in genetically engineered crops, as well as the way these similarities and differences are considered for purposes of toxicology testing.

A field is a complex place, even without consideration of the different types of Bt. Before we get too far into the “weeds”, let’s look at Life in a standard and in Bt maize field, a video produced for the European MOBITAG project. Discussion of Bt begins at 16:40.

[kad_youtube url=”https://youtu.be/oU3X3OLOlBw?t=16m40s” ]

Continue reading “Bt”

The Frustrating Lot Of The American Sweet Corn Grower

Written by Steve Savage

We Americans love sweet corn – our uniquely national vegetable. We consume ~9 lbs of sweet corn per person per year (see how that compares to other vegetables in the graph above). The farmers that grow this crop for us do so on a much more local basis than for most fruit or vegetable crops. There are significant sweet corn acres in 24 states and a total of >260,000 acres nation-wide for the fresh market and >300,000 for canned and frozen corn (see graph below). Sweet corn can be difficult to grow for many reasons, and is often sprayed with insecticides. A biotech solution to this problem exists, but it is under-utilized, in part, due to campaigns by anti-GMO activists. In the end, the people most hurt by this are the American sweet corn growers. Continue reading “The Frustrating Lot Of The American Sweet Corn Grower”

Lit search failures and hazards

On Twitter yesterday, @seekblunttruth shared a link with @franknfoode that I thought deserved greater scrutiny. The link is to an ISIS post* titled Bt Crops Failures & Hazards.

Others may spend some time criticizing ISIS itself, and that criticism may be worthy, but here I’d like to focus on the post. I’ll let you check out the post content yourself, but I want to focus on the works cited list.

There are 29 citations. We find 11 sources that are by ISIS authors. It’s ok to refer to your previous work, we do it on Biofortified all the time, but having almost 40% of the citations be self-citations feels like an attempt to pad the citations list. Many of the rest of the sources are either by biased organizations or have been previously debunked either in the literature or in the blogosphere. Continue reading “Lit search failures and hazards”

Bt FAQ

Bt, short for Bacillus thuringiensis, is a bacteria that produces a protein that kills certain types of insects. Different types of the gene that produces thais protein have been engineered into crops to make them resistant to those insects. The approach has been quite successful but the details can be confusing.

If you’re looking for science-based information on Bt crops, check out the Bacillus thuringiensis info page that was developed by Karen Chien of the University of California, San Diego, with the assistance of Raffi Aroian. The material is a little dated, but it’s still a great resource. I especially enjoy the cartoons! 🙂

The Aroian lab studies the ways that “target pests develop resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis crystal proteins in order to protect this valuable natural resource.” They’re also studying how Bt could be used to treat parasites in animals and people, as in their recent article in PLoS: Bacillus thuringiensis Cry5B protein is highly efficacious as a single-dose therapy against an intestinal roundworm infection in mice (full text).

Thanks to Mica Veihman (@Mica_MON on Twitter) for reminding me about this great resource.