Written by Brittany Anderton

Biotechnology is poised to become one of the most valuable scientific revolutions of the 21st century. Because the field is developing so quickly, the gap between expert and non-expert knowledge is increasing at a time when societal decisions about it are becoming more and more important. So how do we promote biotechnology literacy in the classroom? What should non-experts know about genetic technologies in order to make informed decisions? I conducted a study to answer these questions, and here is what I found.

Even though scientific knowledge is an important part of science literacy, how people feel about a technology – their general positive or negative attitudes – also plays a role in their decision-making. In fact, there’s evidence that attitudes play a greater role than knowledge in determining students’ behavior toward biotechnology. I set out to understand what issues undergraduate students draw upon when they reason about genetic technologies. I also wanted to know whether classroom dialogue about biotechnology influences their attitudes and understanding. This information can provide a window into the conceptual frameworks that students use to make decisions about genetic technologies, and can help educators and communicators develop specific strategies for connecting with their audiences.

Students discuss biotechnology

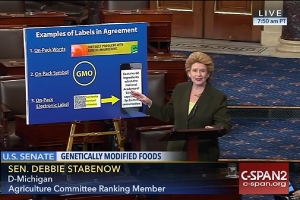

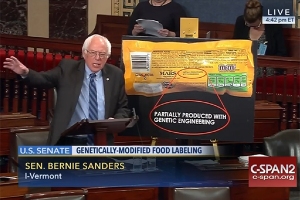

Twenty years ago, my postdoctoral mentor Pamela Ronald launched an innovative course designed for non-science majors at UC Davis. Genetics and Society engages students in the science, politics, social issues, ethics, and economics surrounding biotechnology. It remains popular today. Recognizing the importance of dialogue around this complex topic, Pam introduced “discussion sections” into the course. During the discussion sections, students engage in rational discourse about a biotechnology issue – for example, whether or not all food containing genetically engineered (GE) ingredients should be labeled as “GMO”. The discussion sections provide an opportunity for students to share their thoughts and consider the many facets involved in decision-making about biotechnology. Scientific arguments used in the class are required to be evidence-based, and students are graded on the credibility of their sources. While students in Genetics and Society generally enjoy these peer-to-peer discussions, no one had looked closely at how they influence their understanding and attitudes about genetic technologies.

At the beginning of the course, I asked the students to state their attitudes on seven different biotechnology applications. Three topics related to food: whether or not we should label GMOs, whether GE of plants should be prohibited, and whether GE of animals should be prohibited. I also asked the students to justify their attitude for each topic. At the end of each weekly discussion section, during which a group of students presented on an individual application/topic, I collected this information a second time from the students in the audience. These pre-post attitudes with corresponding reasoning provided the data for my study.

I started by looking for significant changes in students’ attitudes following the discussion sections. I found significant changes for three topics: GMO labeling, GE of animals, and the FDA ban on 23andme’s health reports* (Figure 1). Because the students did not appear to have familiarity with the 23andme ban at the beginning of the course, I didn’t select that topic for further analysis. In the end, I selected GMO labeling and GE of animals, as well as two topics for which I didn’t observe significant attitude changes (DNA fingerprinting and human embryo editing research) for further analysis. Pam and I reasoned that it was important to take a close look at student reasoning in the presence and absence of attitude changes, because learning can happen even if a person doesn’t change their mind.

Analyzing the themes

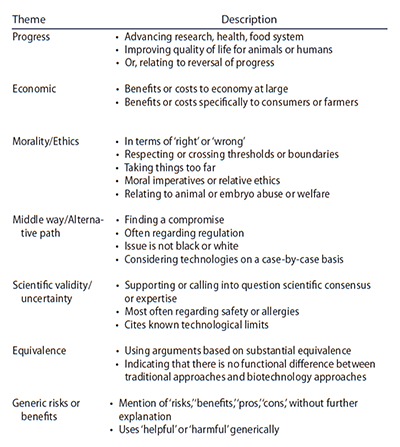

Using the justifications given by the students for their attitudes on the four topics selected above – GMO labeling, GE of animals, DNA fingerprinting and human embryo editing – I performed an approach called thematic analysis, in which I looked for overarching patterns or themes that were prevalent in students’ reasoning about biotechnology. Through an iterative process, I identified seven major themes that students drew upon in their justifications (Figure 2). I also tallied the number of times I detected a change in the use of a theme following a given discussion section (i.e., whenever a student adopted new reasoning or abandoned prior reasoning following a discussion section).

Our preliminary evidence suggests that the discussion sections – and perhaps classroom discourse in particular – provide students with a more nuanced understanding of biotechnology. For example, students generally increased their use of “Middle Way” reasoning following the discussion sections. This suggests that they developed a greater appreciation of regulations that consider biotechnology applications on a case-by-case basis. We also observed increased use of the Economic theme following the two discussion sections for which students had significant attitude changes. It is possible that the economic considerations of genetic technologies can sway people’s attitudes, but this remains to be proven.

Scientific decision-making involves more than just facts. By better understanding the complex processes that take place when students learn and make decisions about genetic technologies – like we did in this study – educators can connect with their audiences and promote biotechnology literacy. A more informed and nuanced discussion will help our society determine the best ways to use biotechnology and to direct our focus as it continues to evolve.

To access the full version of the manuscript, Hybrid thematic analysis reveals themes for assessing student understanding of biotechnology, please go to: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2017.1338599.

Please address any questions or comments to Brittany Anderton at bnanderton@udavis.edu.

*The FDA banned 23andme genetic health reports in November 2013, citing concerns about the accuracy and usefulness of such information to consumers. In October 2015 the ban was lifted, and 23andme resumed offering carrier-status testing, though no longer offers testing for health conditions such as cancer and heart disease.

Written by Guest Expert

Brittany Anderton seeks to improve the intersection of science and society by educating the next generation of responsible scientists and citizens. She has a PhD in cancer biology, studied the teaching and communication of biotechnology as a postdoctoral fellow at UC Davis, and is now the Associate Director of Research Talks at iBiology and Lecturer at CSU Sacramento.