I’m excited to announce today that our first Citizen Science experiment, the “GMO Corn Experiment” is entering its final stage. It has been a long time coming, and I know each and every one of our participants have been waiting to hear the news about our results. I have a lot of things to tell you about in this update, and I’m happy to say that while we encountered some issues with analyzing all the voluminous data that our citizen scientists contributed, we have our results and are preparing them for publication. Along with this update, we want to make sure that every one of our citizen scientists gets a chance to get credit in the final paper.

I’m going to tell you a story spanning the beginning of the experiment right up to today. So to make sure everyone hears the news and gets the takeaways, here is where we are. The analysis of the data from the GMO Corn Experiment is complete, and we are preparing our study for publication. We encountered many difficulties when it came to analyzing all the data submitted to the experiment, but we worked through them and have some clear results that we presented at a scientific conference to get feedback from fellow scientists. We have verified the genetic identity of the ears of corn used in the experiment, and confirmed that they are equivalent in composition. We are sending out a survey to our Citizen Scientists so we can credit them in the paper, and when the paper is submitted we will hold a live broadcast announcement and release some of the results and award prizes to some of our participants who have completed our survey by August 25. Want to know all the details? Read on!

On data and difficulties

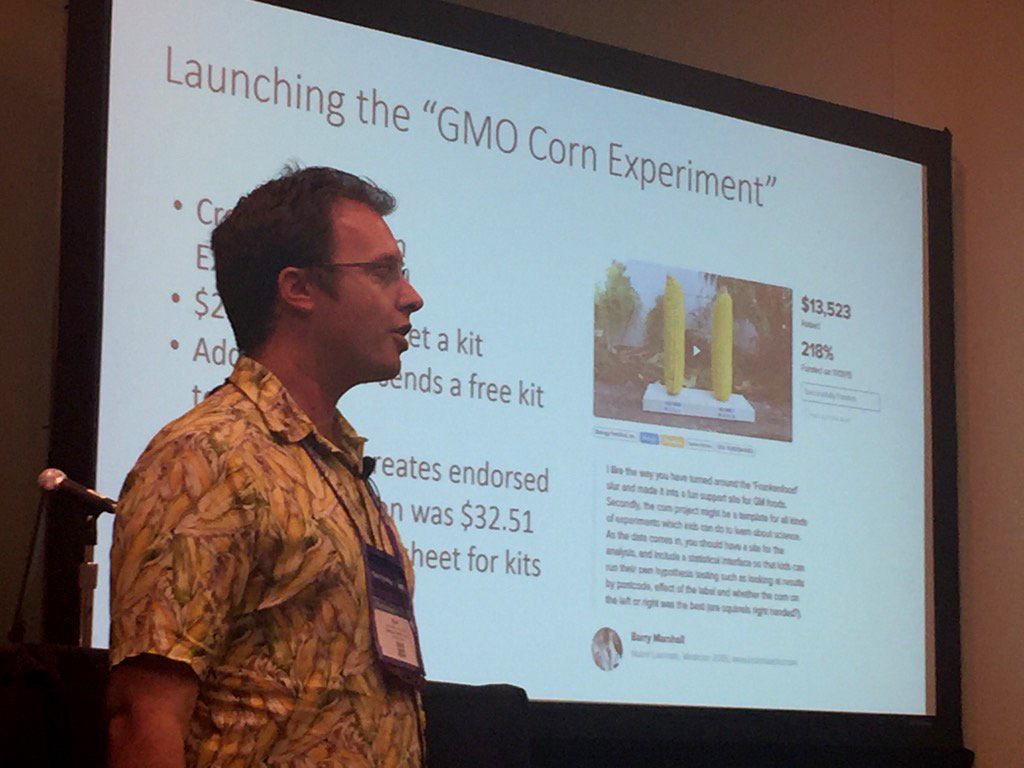

Several years ago, when I initially envisioned this project, I thought it would be nice to have 30, 50, or maybe even 100 experiments. That would give us some good numbers to get a satisfying conclusion. As we prepared to announce the project in late 2015, we were going with that plan. Long before the public announcement of the experiment, I requested ears of corn from Monsanto that we could use to test the claim that wild animals would avoid genetically engineered corn, and they agreed to grow two plots of corn in Hawaii and ship the ears to us. As we prepared for that public announcement, I got an email from Monsanto saying that they harvested 3,000 ears from each plot, and wanted to know how many I wanted. Hmm, how about all of them? 100 experiments turned into 2,000 potential experiments in 1,000 kits, thanks to our enormously successful fundraiser. If some data is good, more is better, right?

A year later, we had hundreds of completed experiments, and about 2,000 observations for us to go through. (Well, for me to go through!) As exciting as it was, this was a daunting task. When planning the experiment, we considered all kinds of ways that our citizen scientists could enter their data, and decided that sending photos would be the best way since we could always refer back to them if there was any confusion.

But analyzing images presented its own problems: how do we make sure that the numbers would be reliable and repeatable? The first thing we tried was to analyze the images based on color. The yellow maize kernels have a specific color, and the images can be analyzed to count up the pixels showing how much of the corn is left on either side of the image. By converting the images into false colors it would be just a matter of adding up pixels. Not only would it be repeatable but it would be done entirely without human judgements and whatever biases might be there. Reliable.

We knew that not all of the images would fit this kind of analysis. Some were blurry or taken at a distance, but if enough experiments made the cut we could use those to make our conclusions. It failed. There was simply too much variation in angles, distances, camera types and more to get good data out of this, as Kevin explained in an update he included in his podcast, Talking Biotech. It would be an easy thing to do if this experiment was done in a lab with a solid black background and a precisely positioned camera, but out in the wild as it were, we needed to find a better way.

Settling the score

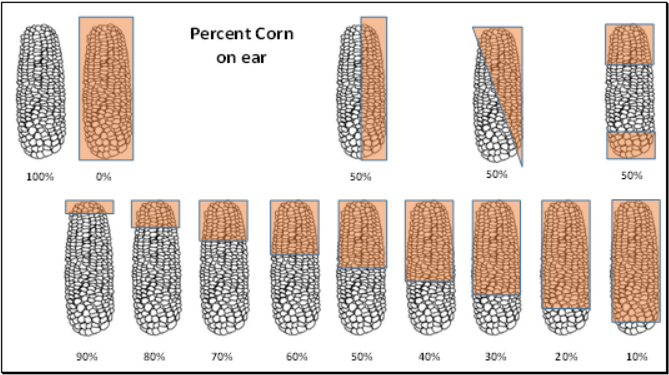

As plant scientists, we went back to our roots with phenotyping. Plant biologists walk through fields rating plant phenotypes on number scales, so we applied that approach to the images. Anastasia Bodnar created a scale, and Kevin Folta gathered a group of volunteers to train and “score” the ears from 0% to 100% with that scale.

There was no need to have them score images that showed no consumption – or even complete consumption of the corn, so I sorted every experiment into one of three bins as to whether no corn was consumed, some of one or both of the ears were consumed, or both of the ears were fully consumed. Since a lot of time elapsed during the first analysis, we scooped up any more experiments completed on the website after our July deadline. By February they were all sorted, annotated, and ready for Kevin’s scoring team. They hammered through all the images and Kevin scanned their hard-copy data sheets so we could enter them into our spreadsheet.

Next came the careful process of checking the handwriting to make sure no 4s looked like 9s, and that the team followed the directions. I searched for individual bias (e.g. did person #3 tend to rate ears as higher or lower than the average?) and the variation was really low between each person. The fantastic thing about this data was that if the ear actually had 75% of the corn remaining, about half of the team put down 70%, and the other half, 80%, giving us an average that would be very close to the real value. Take one or two team members out and the data hardly changed at all.

Repeatable. But was it reliable? How could I tell that no one in the review team was fudging their numbers to prefer one result over another? They were all blinded. They had no idea which ears were GMO and which were non-GMO.

The blinded leading the blinded

Meanwhile, I sent of random samples of the GMO and non-GMO maize kernels that were collected at the start of the project to be analyzed for purity and composition. We needed to make sure that there wasn’t significant cross-pollination between the two plots that could erode our ability to draw conclusions from this experiment. Moreover, we needed to verify, independently, that all of the genetically engineered traits were present in the GMO variety as promised.

There were supposed to be six different Bt traits and two herbicide-tolerance traits to consider, and if it is true that just one of them made wild animals skittish they all needed to be there. We also needed to make sure that Monsanto sent us comparable varieties of corn. If one had less protein or more starch than the other, that could confound our experiment. The tests came back and showed us that there was no evidence of cross-pollination between the plots, all of the traits were where they needed to be, and the compositions of each variety were the same. When the composition samples were sent off, they were assigned random numbers so the testing lab would not know which was which.

The next step, this spring, was to hand off the data to our statistician, Bill Price, who also joined the project. Bill developed some statistical models to analyze the data that came from Kevin’s team. I assigned new numbers to the genotypes in our data (based on the same random numbers I used for the composition analyses) so that Bill could focus on the data and not think about which one was which. He knew from his experience that even “A” and “B” carried meaning so he wanted random numbers. He got “253297” and “442392”. Can you tell which was which? (At the time of writing even I have to go check the spreadsheet to know.)

Why all the layers of “blinding?” Science is the search for empirical truth – knowledge that can be tested and verified through experimentation. Nature does not care what we believe – it operates the way it will – and our task as scientists is to determine the facts as carefully as we can. Human minds are tricky things, though, and we introduce subtle biases – sometimes without knowing it. Good scientists are committed to determining the truth no matter what their prior beliefs are. Doing experiments blinded ensures that subtle biases cannot creep into the experiment based on how we think the experiment should turn out. We also blinded our participants for the same reason. These details make the results more trustworthy for everyone involved – more reliable – and this is a standard that we hope will be adopted by more scientists on all sides of the biotechnology issue.

Presenting to peers

In June, we had our first opportunity to present our results to the scientific community. I gave a talk at the Plant Biology 2017 conference organized by the American Society of Plant Biologists. The conference was held in Honolulu, and brought scientists from around the country and from across the Pacific to learn about and discuss each others research with talks, poster presentations, and social events. I also organized a science communication workshop at the beginning of the conference. Presenting new research at conferences is an important step on the path to publication because it allows your fellow scientists an opportunity to ask questions, propose analyses you haven’t thought of, and generate a little buzz in the community as well.

It can also be a bit of fun. I’ve presented on my thesis research at a maize genetics conference before – the hardest, most nerve-wracking presentation I’ve ever given in my life. But standing in a room of experts, once you realize that you’re the expert on your own research it gets a lot easier. Now add the fact that we’ve got a fun story involving public questions and controversy, Nobel Laureates, funny wild animals, excited kids, and the biggest acknowledgements slide that you’ve probably ever seen. It was a blast! I filmed the talk, so don’t worry – you’ll get to see it. If you were paying attention to our Twitter feeds you may have seen some shots of a slide I prepared for the inevitable news leaks coming out of the conference. I saw cell phone cameras focusing during our big data slides, so I was ready with our social-media-friendly slide right after that. Are you ready?

Boom. Controversial, I know. The scientists in attendance were in good humor with this, so I proceeded to my next, and most important slide. I wasn’t just there to share our research – I had another agenda: to convince my colleagues that research can also be outreach. Afterward, several people told me that this was the most interesting part. We tend to think of research as discovering knowledge, and outreach as communicating knowledge. I think differently. I think that good research can also be designed as outreach, to both discover and communicate knowledge at the same time. And I believe that we can take this model and apply it to even bigger questions about food, biotechnology, and agriculture. Together, we can change the way that science is done and create a better informed society.

Paper the town

We’re getting down to the last phase of our project. With our results in-hand, and our conference presentation and discussions behind us, we’re busy preparing our paper to submit it to a peer-reviewed journal. For those who are not familiar with this step, we’re carefully writing up the methods, formatting the data, and making decisions on how to best present our results so that everyone can understand them, and so that other scientists could replicate them. There’s more data than what I presented in my talk, including validating our methodology, and so our challenge now is fitting it all together as a cohesive article. There are so many ways to present the data, so we’re choosing what tables, charts, and graphics communicate the most information.

The ears of corn we used for the experiment were donated by Monsanto, and we signed a Material Transfer Agreement with them, which allowed us to conduct our experiments with their corn, and laid out everyone’s rights. As part of that agreement, we will be sharing our results and our draft of the paper with them prior to submitting it to a peer-reviewed journal.

This is a very standard practice when scientists are studying patented material owned by someone else, and it ensures that we can publish our results – whatever we find – and they get a heads-up on it before we go to publication. Their scientists may even make suggestions such as how to describe their maize varieties or suggest analyses, but we alone have the power to do anything based on those suggestions. To show everyone how this process works, when all is said and done we will show you what we sent them, what they sent back, and any changes we made based on that information.

Then, the paper goes off to a scientific journal to undergo peer review, where anonymous scientists will pick it apart, rate the quality, novelty, newsworthiness, etc. They may recommend publication, revision, or rejection. We might have to make changes and send it back, and we’ll keep you updated on the process when it happens. When we get it published later this year, we’ll have so many stories to tell about this project. It will make a splash!

Credit where credit is due

We can’t take all the credit – because so much of the success of this experiment is due to the work of our Citizen Scientists, donors, and supporters. That’s why we’re taking special care to make sure that everyone involved, from donors to participants, get credit for their contributions.

That’s right, if you were a part of this project, YOU WILL GET YOUR NAME IN OUR PAPER! Although our list is huge, online publishing has no practical size limits so you will get to see your name preserved permanently as part of the scientific record in a supplemental acknowledgements section. To make sure that each and every one of you get credited the way you want, we are sending out a survey over the next couple days to our study participants. Look for it, and please fill it out right away! If you do not receive it by Monday, please contact us and we will make sure that you get it.

Remember when you signed up for the experiment, we agreed to keep your personal information private. So in order to credit you we need your permission – and the great part of this is if you want to highlight the contributions of your K-12 research team, you can choose how to credit them. If you want to remain anonymous, you can choose that option as well. (Experiment.com donors who did not participate in the experiment do not need to fill out this survey as their contribution is already public and will be included in our acknowledgements.) As an extra incentive for finishing our survey, we’re going to award some prizes for participation.

Did you say awards? Prizes?

Yes I did! Remember how I said that I read through over 2,000 observations? How I sifted through hundreds of experiments, and all the images they contained? I could see all the work you put into these experiments. I could sense the enthusiasm, the creativity, the frustration, and the satisfaction. I remember one citizen science team that kept repeating their experiment over and over again, taking notes saying that no animals touched the corn. Diligently, for two weeks, taking photos, resetting the experiment, and gathering weather data. Then came the day that they finally attracted the attention of wild animals, corn was getting eaten and exclamation points were everywhere. I half jumped out of my seat! That kind of dedication deserves recognition.

More teams impressed me with their detail-oriented approach – taking careful and comprehensive observations. Others took incredible and sometimes hilarious photos. There was some good humor involved in some of the experimental data – “kids” in the list of wild animals active in the area, signs posted in the background of their experiments, and prosaic observations. I could see some future scientists in there. We need an award ceremony.

When you get the survey, fill it out and you are entered to win one of several awards for your participation, including several randomly-selected prizes. Fill it out by August 25th!

When we submit our paper we will hold a live streamed broadcast to announce the submission, release some of our results to the public, and celebrate everyone’s contributions and announce the awards. Stay tuned, because the most exciting part is yet to come.

Great Job Karl and Team! Giant value in this experiment and even more so in the set up and how to carry out the blinding. I love this experiment and had great fun explaining it in class. It’s an excellent out reach tool.

LikeLike

Nice comment in your survey response, too! I did a double-take. I do believe that will come up at some point.

LikeLike

I filled out my survey this morning! Can’t wait to see the data.

LikeLike

Fun experiment. I worked on corn genetic engineering for many years. I look forward to seeing the results. It would be nice to have more information on the growing conditions and soil assays for the field(s) the corn was grown in. The exact same corn variety with and without the added traits, might be influenced more by the soil types, micro climates, and biotic and abiotic stresses, than any potential influence of the added traits. Ideally, the corn lines would have been grown in multiple blocks, with in one soil type, with the same agronomic practices, to try to average out the environmental effects on the lines.

LikeLike

We will have more information about the growing conditions and field locations in our paper, as well as the sprays and other treatments that were applied to the crops. We just had two big blocks of the similar varieties, sufficiently close to be very similar conditions, but sufficiently far to not cross-pollinate with each other. It would make a better experiment to do additional blocks, however, at the time the corn was planted we were not thinking it would become so big of an experiment!

Next time we’ll think bigger.

LikeLike

What is your hypothesis regarding how the variables that you mention would affect whether or not animals would eat the corn and/or how much they would eat? Animals eat every kind of corn everywhere it’s grown.

LikeLike

Lisa, i have conducted experiments looking at the influence of soil and weather on the nutrient content of crops. Soil variation and weather and microclimate differences can result in changes in nutrient quality of the plant or grain. This could influence animal feeding choice.

LikeLike

Not without knowing what kind of hunger the animals are experiencing and what other foods they have access to. Plus, how would you control in order to learn the effect?

LikeLike

Also, supposedly GMOs are evaluated pre-deregulation to ensure that they are nutritionally comparable to the corn from which they’re developed. So if they’re grown in similar conditions (as Karl has told us that Monsanto said they were) then there should be no nutritional differences.

The hypothesis you’re wanting to test is: do wild animals prefer different varieties of corn based on the corn’s nutritional profile? for which we’d have to evaluate the composition of the corn, not the soil it’s grown in. You can’t assume that growing corn in different conditions will cause a significant difference in nutritional content, although it’s a good guess that it will.

LikeLike

Lisa, there are no nutritional differences, but that is not what this experiment is about anyway. What is your point?

LikeLike

Ag, you can’t say there are no nutritional differences without doing tests on the corn. We can make an educated guess that they’re similar because they start out as the same kind of corn and were grown in similar conditions. But some engineering changes the nutritional profile. There’s just no way to know, and, as you say, that’s not what this experiment is about. My point is the same as yours. If you read Williams comments, hopefully mine will make more sense to you.

LikeLike

Agscienceliterate and Lisa Makarchuk, Soil fertility and weather can make substantial differences in the nutritional quality of plants. For examples, while working for Monsanto, we had GMO corn grown at two locations. The protein levels of the gene of interest were orders of magnitude different depending on where the crops were grown. I used to conduct choice tests on insects to understand insect plant choice in greenhouse settings. Chemical clues are used and can be influenced by slight environmental differences on the plant. One of the most startling examples that ruined one of my experiments in 2015 was a fertilizer trial in alfalfa. This was a university run replicated trial looking at plots of several different types of fertilizers and no fertilizer control plots. White tail deer had a trail worn through non-fertilized border areas of the alfalfa field, straight into our trial blocks and there was extensive feeding damage done to the plots with fertilizer. There was no feeding damage to the no fertilizer plots. In talking to the collaborator in the study, he mentioned that he has observed wildlife preference for fertilized plots over non-fertilized plots in the past. I would have to look up the literature on it to confirm, but from an evolutionary point of view, it makes sense to me that animals will seek out and choose foods that are more nutritious versus less nutritious. Seeing as this study design is a side-by-side choice test, if one does not control for environmental influences on the corn, such as variation in soil fertility, slope of the fields etc. there could be variations in nutrient status of the plants/grain, and that could influence the study. One might draw the wrong conclusion about GMO versus non-GMO versions if the plants were not grown in a controlled experimental design.

LikeLike

I thought it was understood that the corns were grown in Hawaii under conditions as similar as possible with regard to environment. The experiment is set up to test animals’ preference for the GE traits vs no GE traits. It would be impossible to add the variable of nutritional differences and still test for the GE trait alone. And if the GE were to cause a change in nutrition, then it is still the GE trait that’s being tested for – since it was the cause of the change in nutrition.

Can you please educate me on what this means: “protein levels of the gene of interest were orders of magnitude different depending on where the crops were grown” TY

LikeLike

The author Karl responded to me that they did not sufficiently control for variable environmental influence. See comments above. As for variability in protein expression, we had a gmo corn line expressing a protein. When the corn line was grown in California, we had one level of protein expression and the exact same corn line grown in Washington State had a significantly different level of protein expression for the gene of interest. Ask any dairy farmer about variation in nutrient quality in feed crops. I spent the morning analyzing alfalfa plant analysis assays. All the same genetics, but varies by fertilizer treatments. There was variation in protein, fiber, most minerals.

LikeLike

TY – I do understand that there are nutritional differences that occur as a result of environmental influences, and that gene expression is influenced likewise. I thought that the corns were grown in similar conditions, including soil, but perhaps I am remembering that wrong.

If this experiment were meant to find if it’s the trait alone and nothing else that makes any difference to the animals, then the dissimilarity in growing environments does throw a monkey wrench in the works, because without controlling for compositional differences caused by different environments, we don’t know whether the animals are choosing based on the trait or on some other difference. (which is what you said from the beginning)

The “experiment” is meant to debunk (or prove :)) the myth that wild animals won’t eat GMO corn. So, as long as some animals eat some GMO corn and some non-GMO, the stated goal of the experiment is achieved. If one corn or the other is rejected, your point is that we can’t say it’s because of the GMO trait without knowing whether there was some other difference between the corns.

Good point.

LikeLike

William, also – my original comment to you was about not being able to control animals’ access to other foods elsewhere, which might possibly influence their choice to eat or not eat any the food provided by the experiment.

LikeLike

Yes, That insufficient control over the growing conditions could lead to compositional dissimilarities in the two corn lines. This is in addition to the plus/minus gmo trait. If animals eat both lines equally, then that is fine. If animals show a preference, then we cannot know why they showed a preference because it could be due to nutritional differences of the grain, the gmo trait, or both.

LikeLike

Lisa, if a raccoon or a squirrel is very hungry, and it has a choice between GE and non-GE corn, which are 6 inches apart, then it doesn’t matter how hungry they are. Because they can still choose which to eat. That is the purpose of the study. Just like if you are really really hungry, and you have a choice between one type of hamburger and another type of hamburger. You still choose which to eat. I’m not sure you understand with the study was about…

LikeLike

If a raccoon is very hungry, and it has a choice between GE and non-GE corn, I predict it will eat whichever one is closer 🙂 LOL – sorry but you seem to be reading my comment out of the context of the discussion it was a part of! William was speculating that nutritional content would influence the animal’s choice. I was pointing out that it would be impossible to learn that in this experiment, regardless of how the corns were grown.

LikeLike

And that is all it is: a prediction. It means nothing until the results are in. I took part in the study (did you?), and I can predict from now until Sunday, but that mean squat until we see what the results are. The speculation, and note that it is only speculation, that an animal will somehow choose food that is more “nutritious” is not part of the study. Maybe, like people, they will merely go after what tastes better. Choosing the donut over the kale, for example. Interesting, but totally irrelevant to the purpose of this study, which I will not re-state yet again.

LikeLike

ARRRGGG! I did not say anything about nutrition except in reply to your or others comments!

LikeLike

I missed knowing about this when you were recruiting, but I’m going to keep my eyes peeled in future in case you run other studies like this. It’d be awesome to take part.

LikeLike

My son and I so enjoyed participating in this experiment. He’s almost 8 now and I can’t wait to see the results and share them with him!

LikeLike

Great study, and I am looking forward to hearing about the results! Thank you, Karl and research team, and volunteers.

LikeLike

Which results? Because if you don’t know that animals have no preference between GMO and non-GMO, then you are NOT (as your moniker claims) “agscienceliterate”

LikeLike

Lisa Makarchuk said, and then deleted, the following snarky comment to me: “Which results? Because if you don’t know that animals have no preference between GMO and non-GMO, then you are NOT (as your moniker claims) “agscienceliterate.” ”

My reply to her, and to anyone else who is interested, is the following: Lisa, my eyeball observation was not scientific, nor was it meant to be. The fact that it was a double-blind study is what makes it scientific. The way the authors are going to determine whether critters avoided GE corn or not is by literally counting the kernels left on each cob. That is scientific. I was merely a participant, not on the teams that assesses whether animals avoid GE or not. By my own observation, it seemed that they did not. But the folks who did this experiment will verify that one way or the other. Got it?

Oh, it seems that Lisa posted a snarky comment and then deleted it. I will leave my comment up here in case she comes back to read it.

LikeLike

Sorry agscienceliterate. I made several comments, and then decided that the one I’d made to you was just mean and unnecessary, so I deleted it.

You said:

“… I am looking forward to hearing about the results!”

I said:

“Which results? Because if you don’t know that animals have no preference between GMO and non-GMO, then you are NOT (as your moniker claims) “agscienceliterate.”

So, as you said – my comment was snarky. That’s why I deleted it. Not sure why you chose to post it after I deleted it. Just to prove that I can be snarky? Congratulations! You proved it!

We all say things we regret. There was no need for me to get personal. Hopefully I will consider my temperament before I post anything like that again.

The results of the study will show whether or not animals like squirrels (for example) show any preference for non-GMO or GMO corn. But there’s no basis for a claim that they might have a preference when there’s so much evidence that they don’t. Many different kinds of animals, including wild animals, have been eating GMO corn for years in the same fashion by which they ate non-GMO corn. People familiar with agricultural science know that. And that’s the reason that those who brought this “research” into existence did so – to “scientifically” prove something that’s already known. There was never a chance that pro-Monsanto scientists were going to risk “proving” that squirrels would rather eat non-GMO corn!

Thanks for the chance to apologize.

LikeLike

Apology accepted. Not sure of your meaning in your response, though – are you implying that Monsanto somehow influenced or biased this study? You note that there is no basis for a claim that animals will prefer one to the other. That is precisely what does study is to show, to those many people who insist that livestock refuse to eat GE corn. I myself will not to predict the results of this study, until I read about the results. Although I presume that animals don’t care, and do not to choose one over the other. I do not know that to be so. Hopefully this study will get us farther along in getting the answer to that question.

LikeLike

Thanks. OK – it turns out you are just a really nice strait forward person.

No, I absolutely am sure that Monsanto was NOT involved in this study in any way except to provide the corn and information about its growing.

I understand that there are people who insist that livestock refuse to eat GE corn. I just think this kind of so-called research in inappropriately used in the classroom to influence young people’s impressions of GMO crops under the guise of “teaching science”. The educationally valuable part of this experiment is the methodology. But because the context isn’t carefully considered, many kids will learn: “GMOs and non-GMOs are the same” I know that’s not what we’re TRYING to teach them, but that’s what they’ll learn unless there is careful and thorough teaching on what the differences actually are (as I tried to describe in my earlier comment)

LikeLike

Sigh – you have leapt to the conclusion that the purpose of the study is to “influence” students about the sameness of GE and non-GE corn. That is NOT what this is experiment is about. No one has ever said that they are the “same.”Read it again. It is only about one thing: do animals prefer GE or non-GE corn? No presumption of “sameness” here. The presumption you arrive at is entirely based on your own speculation. That is not the purpose of the study. Again, read the study and the limits of what it attempted to discern. And wait for the results before you jump to conclusions. (Sigh…)

LikeLike

more than 90% of the corn growing in the US is GMO. Wild animals are eating it. If anything, I’d expect a preference for GMO if the trait has any influence on flavor or other appeal – since the animals have adapted to and are now conditioned to eat GMO corn.

LikeLike

Again, your expectations and presumptions are based solely on speculation.

Wait for the study results before jumping to conclusions.

LikeLike

Ag, deer, raccoons, crows, squirrels, etc. all eat corn in the field.

LikeLike

Well, science has shown us that they are not different in any meaningful ways from a consumption standpoint.

LikeLike

You mean because animals eat them?

LikeLike

No. I mean because decades of testing has not found any substantial difference to the consumer.

LikeLike

I don’t want to get into a discussion with you that’s going to create a link war. I’ve had that discussion on this very site more than once. What you’re saying is meaningless. “decades of testing” is a broad sweeping generalization that I can’t respond to without extensive writing, and doesn’t apply to any particular consumer goods. And substantial is a subjective word. Sorry Jason – that discussion is off-topic and too involved. I’ll give the last word to you.

LikeLike

It’s not really to involved. Literally every single governmental science, regulatory & food safety authority on the planet that has reviewed this has reached the same conclusion. They are equivalent.

LikeLike

Again, you’re making broad sweeping generalizations. There’s a continuing debate on the term “substantial equivalence”. I think you’re putting forth the industry’s meme “they are equivalent” – but scientifically they’re not. So – it just depends what you want kids to learn.

Squirrels eat both: kids (inadvertently?) learn they’re equivalent (industry stance)

One kills bug: kids learn they’re not equivalent (scientific fact)

Analysis will not show the corns to be the same. And various tests would have to be done to show the extent of their differences and then to determine the significance of those differences.

You have to be careful how you present things to a child – they often learn things you never meant to teach them.

LikeLike

No…not at all. I’m saying, specifically, that GM crops currently on the market are equivalent from a consumption standpoint. That is not a generalization at all.

Wrong again. I’m putting forth the consensus opinion of every major scientific organization on the planet. So, scientifically, yes…. they are.

Also the stance of the National Academies of Science, along with every other major scientific organization.

That’d be important to teach kids who want to be farmers but an irrelevant fact for any that don’t.

Actually, analyisis has shown exactly the opposite. Bummer, huh?

Well, we finally agree. That’s why it’s best to stick to the science rather than the nonsense you’re pushing.

LikeLike

You’re using your terms very loosely and making broad claims. I’m just saying kids ought to be taught science without commercial product placement, unless that placement is within a critical context.

“That’d be important to teach kids who want to be farmers but an irrelevant fact for any that don’t.”

Who are you to decide what’s irrelevant in kids’ science education? Science is science is science. It’s not different for different kids.

LikeLike

Finally we agree. Science is science and the scientific consensus on gmo crops is that they carry no unique risk compared to other crop breeding methods and they have been show to be nutritionally equivalent.

So I guess that’s what we should be teaching kids. Don’t you agree?

LikeLike

We should teach kids science. GMO corn and non-GMO corn aren’t the same. Teaching kids that they’re the same isn’t science. If you want to make comparisons as to how the corns might be similar, you do that within a discussion of similarities and differences.

LikeLike

But corn that has wide leaves isn’t the same as corn that has narrow leaves. Yet we teach people that that both plants produce corn.

Corn that resists gray leaf spot disease is different than corn that doesn’t. Yet we teach that they both produce corn.

Corn with a high starch content is different from corn that has a lower starch content. But we teach that they both just produce corn… standard #2 yellow dent corn. Just like GM corn plants do.

Production traits aren’t the same as consumption traits and I’m quite confident “science” agrees. Sounds to me that you don’t understand what is and isn’t science.

LikeLike

All the corns you’ve listed are corn, but they’re not the same. You seem to be suggesting that we should categorize the different corns in a way that allows us to teach kids they’re the same without being inaccurate. What is the purpose of doing that?

LikeLike

You’re right. We should start educating kids on every minuscule production difference in every commodity crop that is produced regardless on its impact to the final product. What was I thinking?

LikeLike

I don’t think we should educate kids on every minuscule difference between commodity crops. I said we shouldn’t teach them that a GMO and non-GMO corn are the same because it’s not a scientific fact.

The final products are very different. That’s their value. Is it a minuscule difference that a GMO corn can kill a bug that eats it and withstand applications of various herbicides? Why would you want to teach kids that GMO and non-GMO corns are the same?

LikeLike

Again…according to every analysis ever, the final products are not “very different”. In fact they are substantially equivalent. Obviously, the final product has nothing to do with killing bugs or weeds. The final product is food, brainiac.

LikeLike

Farmers buy the GE corn for its unique ability to withstand herbicides and kill certain pests. The final product is the corn, regardless of whether it’s used for fuel. feed, or whatever. The issue isn’t substantial equivalence, which is another topic and doesn’t mean that the two corns are “the same”.

No need to be rude.

LikeLike

See! You’re talking about production traits, not consumption. My point all along!

Glad we could finally agree.

And maybe you should look up what equivalence means?

LikeLike

“you’re talking about production traits, not consumption”

The corns are molecularly and compositionally different, and they have different traits because of that fact.

One carries traits like herbicide-tolerance and insect-resistance.

Both corns are corn.

They are similar and can both be fed to animals as feed.

You and a few other people on this page are suggesting that children who participate in this experiment shouldn’t be taught that the two corns are different.

But without that fact – the experiment is meaningless!

We are comparing two different corns.

Why would we do that if they’re the same corn?

THEY ARE NOT THE SAME CORN.

Why don’t you see if you can confer with Karl if he’s willing?

I feel confident that he’ll tell us that participants aren’t meant to conclude that the two corns are the same.

I’m curious. Why do you think we’re doing this experiment?

LikeLike

All corns, whether GMO or not are molecularly and copositionally different. So the question is whether or not they fall into the “normal” range.

GMO corns do, so they are considered substantially equivalent.

I’m sorry. It doesn’t matter how many times you you repeat this claim. You’re wrong. The entire scientific community disagrees with you on this and I’m pretty sure they know more about it.

LikeLike

Jason, what is the purpose of the experiment?

LikeLike

The experiment is being conducted to test the common activist claim that animals will choose non-gmo corn whenever given the choice. Simple as that.

LikeLike

We’re putting out two corns for the wild animals to choose between. Are those two corns the same?

LikeLike

As same as any other two ears of corn from different hybrids. Same enough to be included in #2 yellow dent corn. (As all other corn is)

LikeLike

No science teacher or academic scientist would ever agree with you that the two corns are the same for purposes of this experiment or for education purposes – or scientifically for that matter. If the only way you’re willing to compare the corns to each other is by saying they’re both corn and animals eat both of them, then no one can disagree with you.

Since there’s been so much repetition in our comments, I’m beginning to sense that it’s important to you to have the last word. So I hereby grant that to you.

Enjoy your evening!

LikeLike

Why do you insist on constantly being wrong?

LikeLike

you edited your comment after I replied. Not a big deal as far as the content – but not cool netiquette. 😦

LikeLike

Sorry, dear. But I did no such thing. I saved my response and then edited it immediately. If you saw otherwise that was unintentional.

LikeLike

It’s ok honey.

LikeLike

I buy GE corn for its unique ability to withstand less toxic and more effective herbicides. All corn withstands certain herbicides.

I went from using more persistent and more harmful herbicides when I switched to GE corn. I raised both types until 2016.

I also raise potatoes and alfalfa. I look forward to the day when I can plant a GE potato that is inherently resistant to late blight. Now, I must spray a fungicide each week through July and August to keep late blight from killing the crop.

There is a new low-lignin trait released for alfalfa. When I am able to use it, I will have more nutrition per acre using the same inputs… a win for the environment.

LikeLike

I wish you well. Let us know how it goes.

LikeLike

J. R. Stewart, I had read on the GM potato a couple of years ago. If you’re referring to the John Innes Centre’s potato – It is still a ways off. I think some of the Sarpo ones are too, and

I don’t know what scale you’re growing potatoes, but you might be interested in this:

http://sarpo.co.uk/sarpo-potatoes/

http://www.potatobusiness.com/storage/control/2064-solynta-develops-late-blight-resistant-potato-varieties

again, wish you well

LikeLike

Are your kids bugs, specifically grubs? If not there is no difference to the kids.

LikeLike

You just said we ought to educate kids about the difference between the corns! That they should have more education and learn about AG!

LikeLike

Why shouldn’t we educate children the difference between corns? more education is better. Kids today have no idea about AG and this should change.

LikeLike

Exactly. That’s what I’m saying.

LikeLike

I think what Jason is saying is that there is many different types of corn, but they all look like corn. Can you tell the difference between flint corn and dent corn, or sweet corn and MBR corn ?

LikeLike

that’s the point of the experiment. The corns look alike to us, but they’re actually different. Will a squirrel want to eat both? If so – what does that mean? To a child of a certain age, the conclusion drawn from animals eating both is: the corns are the same. But we know that they’re different. We want the kids to understand what’s going on and why we’re doing the experiment. What would be the point of doing the experiment if, as you say, the two corns are the same? And why would you want kids to learn something that isn’t true. There are reasons for corns be different from each other, and they’re still all corn. Don’t we want to teach kids facts and critical thinking? How the experiment is presented, and what conclusions are drawn will be as important as methodology and results. Thank you.

LikeLike

There are more differences between two different varieties of conventional corn than there is between a variety of corn without a GE trait, and the same variety of corn with the GE trait.

I agree that GE technology should be taught–it would certainly help stamp out this ridiculous ignorance that seems to be prevalent among a certain sub-set of our population.

LikeLike

There are qualitative and quantitative differences in each case. The significance of those differences can’t be elucidated in a straightforward way. This is ongoing research. But I understand what you’re saying.

I made a comment about unwitting lessons kids might learn from the corn experiment, and it seems there are several people who want to debate the substantial equivalence of GMO and non-GMO corn. I’m not willing to do that in the context of this discussion. I’m just suggesting that we need to be careful what we imply when we’re presenting this kind of study to kids of a certain age.

We agree that GE technology should be taught.

LikeLike

Yes there is a difference between a phillips 1″, Binding Head 8-32 SS-316 machine screw and an starhead Binding Head 8-32 SS-316 machine screw. But both perform exactly the same and the same functions and can be used interchangeably.

LikeLike

What’s your point?

LikeLike

The point is that though there is a technical difference, they both hold together the car they are in equally well.

LikeLike

So what? What does that have to do with this discussion? Should automotive students be taught that all these screws are the same? Should science students me taught that GMO and non-GMO corn are the same? If both corns are the same, what’s the point of feeding both to squirrels to see which they eat?

LikeLike

The hypothesis, made by the anti-gmo crowd, was animals, such as squirrels, would favor corn whose genes were changed without a priori knowledge as to which would be changed and to what, to wit, without GE techniques.

This study tested that hypothesis and shown it to be false.

The car is analogous to the corn. The screws are analogous to proteins. The phillips head could be considered the non-gmo version of the resultant protein. The starhead the gmo version. The starhead makes it easier to assemble the car with fewer stripped heads and more precise torquing of the screw. In the end, though, the car is the same as far as the driver is concerned, analogous to the consumer of the corn.

In other GMO’s such as golden rice, this would not hold. Beta-carotine in rice would be a definite difference to its consumer, in almost all cases, for the better.

LikeLike

The reason that the starhead makes it easier to assemble the car with fewer stripped heads and more precise torquing of the screw IS BECAUSE IT’S NOT THE SAME AS THE PHILLIPS HEAD.

Consumer is equivalent to driver.

Automotive student is NOT equivalent to driver.

driver is NOT equivalent to science student.

The experiment was to do the research you described, but it was also billed as educational. And although it’s educational, it’s also mis-educational UNLESS the difference between the corns is made clear to kids of an age to learn false lessons like “both corns are eaten by squirrels, therefore they are the same”

That’s the extent of what I’m saying.

You, like others who seem to want to argue with me, are putting forth something that has nothing to do with what I’m saying. You’re saying that kids are consumers and the differences between the corns aren’t important to teach because they’re not relevant to consumers.

If kids are doing this experiment, they’re learning. They’re students. We’re supposed to be teaching them why and how to do science experiments. If the corns are the same there’s no point to the experiment. If the corns are the same, then the answer to the anti-GMO myth would simply be: the corns are the same, so YOU have to scientifically prove that animals differentiate, because there’s no reason for them to do so. The myth says that animals differentiate BECAUSE one corn is GMO. It doesn’t say animals differentiate because the corns are the same. Putting out two corns that are the same and expecting animals to differentiate is stupid.

THEY ARE NOT THE SAME CORN AND THAT IS THE BASIS FOR THE ANTI-GMO CLAIM AND THAT IS THE REASON FOR THE CORN EXPERIMENT.

Please, if you want to engage or argue with me, respond to what I’m saying, not to some idea you’ve got that it’s important to say the corns are the same. They’re not the same they’re not the same they’re not the same infinity.

LikeLike

It’s BMR, hz. Brown mid-rib. A low lignin corn where the corn stalk and leaves are more digestible than the typical corn plant. This corn is grown exclusively for silage–to raise it for grain corn would be a foolish waste of money! 🙂 Seed is big $$$. (It is also a conventionally-bred trait).

LikeLike

I know.. I make the same spelling mistake all the time…

From now on, I will just claim that MBR is Canadian for BMR corn.

LikeLike

I knew it was a typo…therefore the smiley face. Just saying hi again. Glad to see you still around.

LikeLike

Just because it is scientific consensus doesn’t mean that it follows that it is true. Several of the reasons pointed out by the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead, according to my poorly framed way of put it, are: 1. all science is limited by its premises; 2. scientific observation is mediated by its means of observation: whether it is through eye or instruments, what we are seeing is not the real thing itself; 3. facts select one set of relationships from infinite ones that any object is involved in (I think that we call this establishing controls); 4. higher levels of organization above organism, such as ecosystem and the ecosphere can’t be explained, understood or predicted in terms of lower ones (this was a principle from James Feibleman). For the first two reasons Whitehead says that science can only approach truth. The latter two mean that one can’t assume that observations that hold true in one level are to hold true in other circumstances at levels of organization beyond the organism. GMOs, and even hybridization, are significant because though they are introduced to deal with single problems which, like other technologies, have broad impacts at ecosystem and ecospheric levels. How can these be anticipated or accounted for? And when there is so much investment and powerful political interest involved in expanding their use, how can we protect ourselves from unanticipated results? Whitehead consequently would say we should be teaching kids that what we don’t know is most significant and, particularly as we introduce changes that are increasingly powerful and having ever broader impact, we should be extremely cautious and be ready to back off when things don’t work.

LikeLike

In the continued absence of evidence that it is untrue, it becomes less & less likely that it is so.

LikeLike

Hi Lisa,

I’m a farmer who also runs a dairy. We raise corn for our own animals. I farm 75% non-GMO.

We collect data continually–measuring how much feed is offered, then we push out the remaining feed and weigh it. We also collect data on each cow. Each cow is measured each day for the amount of milk she gives. Cows are also periodically weighed, and judged on body condition. We track feed carefully, and we have noticed differences in feed that would be practically impossible to measure without careful collection of data.

For example: We found a difference in feed on how FAR away from the feed mixer that the pen is. Yes–the pens further away showed a difference. We figured out that the difference was because the person who feeds was leaving the mixer running while he was driving to the pen–therefore, the pens further away had feed that was chopped up and mixed more than the pens that were close.

In another instance, we found that the fields that were on the north side of the road had a difference from the fields that were on the south side of the road. What was it? Our prevailing wind is from the south, and dust that was otherwise unnoticeable was detected in how the cows responded to the feed.

What about GMO? We’ve never seen an iota of difference in the animals preference or performance. Different varieties? Yes! Cattle will perform and eat differently with different varieties of corn (and other crops as well).

What about the same variety, but one with a GE trait? No difference.

However, I would expect if that GE difference were a “feed value” difference–such as increased starch, or decreased lignin, then there would be a detectable difference. However, there is no detectable difference when using either the RR trait or the Bt trait.

LikeLike

Hi!

Thanks for writing about your interesting experiences. Certainly animals can distinguish some differences between different feeds – taste, smell, texture. But we know that other farmers share your experience that animals don’t differentiate between GMO and non-GMO feed based on those traits alone.

That is, there’s no reason to believe that squirrels and other wild animals will prefer non-GMO over GMO corn. My contention was that, regardless of whether or not any animals distinguish a difference, it’s not correct to imply that the corns are the same (especially in a classroom setting).

I’m sure you’ve chosen to grow GMO corn for some reason other than that your cows can’t tell the difference. Thanks again. 🙂

LikeLike

I am assuming there will be a book release and concurrent press embargo upon publishing?

LikeLike

This experiment was a missed opportunity to teach kids about GMOs. Regardless of the good experience they may gain in conducting research, the unwitting lesson for kids is: GMO corn is the same as non-GMO corn. (something that is scientifically false)

It’s important to be cognizant of the real lesson kids are learning in such “outreach” from the biotech industry.

LikeLike

Lisa, that is most certainly not what this experiment intended to show. It intended to show one thing and one thing only: do critters to eat corn, such as squirrels and raccoons and birds, intrinsically prefer one type of corn, GE or non-GE, to the other? You are confabulating a lot of presumptions that are not part of the study in question. This is an excellent learning opportunity for children, to learn about double-blind studies. I hope you are not a teacher.

LikeLike

If I were the teacher administering this “experiment” – I would make sure that the kids knew that there was a difference between the corns that animals have not been shown to have any ability to discern. And that just because a squirrel eats both corns doesn’t mean that they’re the same.

Please note: I said UNWITTING lesson. That means: the lesson you never designed to teach. A good teacher knows that kids don’t always learn the lesson you’re trying to teach, but may instead learn a lesson about the context in which you teach it. If the lesson is about gender roles and how they’re unscientifically constructed, but the teacher only calls on boys to answer questions – there is an unwitting lesson that girls answers aren’t as valuable.

So, in the case of the Corn Experiment, we are indeed teaching a process – but we are also UNWITTINGLY teaching that GMO corn is the same as non-GMO corn because animals eat both. The teacher will have to take special care to make sure that the kids don’t make invalid conclusions based on the results.

A better experiment to teach about GMOs:

Teach kids that some corn is engineered to withstand herbicide that ordinarily kills corn. Let them figure out how to test which of two corns is glyphosate-tolerant. (Grow glyphosate-tolerant corn and non-glyphosate-tolerant corn. Spray the two with glyphosate and observe the results). Kids are mesmerized by seeing that two things that appear to be identical are actually not. Such an experiment would be a great way to introduce genetics and genetic engineering to kids.

A similar experiment could be done with bt trait.

LikeLike

So you have already concluded, before Carl has even done the analysis, the animals will not make any distinction between the corn? Curious. Did you even take part in the experiment yourself? How is it that you have come to this conclusion that Carl hasn’t even come to? And your proposal for an entirely different story, albeit interesting, does not get out what Carlos trying to discover. It is an entirely different study that you are proposing. Perhaps you may want to try to get funding for it. But that is not the study that is being discussed year, which is solely about animal preference for GE or non-GE corn.

LikeLike

I was just trying to point out that tying the experiment to education for young people is a mistake unless the teacher who administers it is capable of clarifying the scientific facts involved.

LikeLike

Well, obviously. If a teacher misinterpreted this as a study about the “sameness” or equivalency of GE and non-GE corn, that would be a misinterpretation of the study, of course. The study is ONLY about wild animal preference. Period. I would expect any grade school teacher to understand that simple concept if they read the study. Pretty hard to misinterpret it.

LikeLike

It’s not about what the teacher interprets, it’s about what the kids learn. In order to avoid false conclusions on the part of the kids, the teacher will have to step outside the experiment and teach the science on genetic engineering. For younger kids, this will be hard to grasp. Young kids will learn from what they see: the two corn look the same, the animals eat both corns the same – therefore, in the mind of a child – they are the same. This is why, if we want to teach the science on GMOs to young people, it would be better to illustrate that two corn that look the same are different, and NOT as they appear to be.

It’s not that it’s WRONG to do this experiment. Perhaps I should say that so that it’s understood that I’m not making a criticism of the methodology or reasoning.

It’s that it’s WRONG to fail to teach the scientific facts that set the context of the experiment. There needs to be a discussion about the corn being different, and HOW they are different. Kids have to understand that although the corn look the same and get eaten the same, one will not die when herbicide is applied. And certain bugs will die when they eat one and will not die when they eat the other. Without these discussions, the lesson is: animals eat both the same. Yes I know that’s not the purpose of the experiment, but that is the result when using it to teach kids.

Without the science, this research becomes a lesson in equivalence. And while for the very narrow purpose of disproving an urban myth, that is perfectly valid – in the context of classroom education, it’s backwards. We want to teach kids how to find out if two things that appear to be the same really are indeed the same. THAT is scientific research.

Besides, the whole experiment is invalid if the animals have been eating GMO and regular corn in their environment prior to their encounter with the set-up.

LikeLike

Your off-subject reasoning is beyond my capacity for response. I think you should complain to Karl. I’m just shaking my head.

(And hoping you are not a teacher.)

LikeLike

I think you’re trying to hurt my feelings.

LikeLike

Well, actually, what they should understand is that all corn will die when sprayed with some herbicides yet not with others. For example, Roundup Ready corn will die when sprayed with Imidazolinone. Clearfield crops will not. Clearfield crops will die when sprayed with glufosinate, Liberty Link crops will not. Liberty Link crops will die when sprayed with glyphosate. Roundup Ready crops will not. All will die when sprayed with Clethodim but none will die when sprayed with dicamba.

All of these corn are different from a production standpoint, but not really different at all from a consumption standpoint. Shouldn’t that be what we teach kids?

LikeLike

Jason, with kids of a certain age it would be too confusing to try to teach them about all the different pesticide-resistant traits and the pesticides themselves. If we want to teach kids about GMOs we can do it with interesting experiments that show what GE can do.

It does seem that you agree that one aspect of the lesson kids might learn from the Corn Experiment is that from an “attractive food” viewpoint, the two corns are the same. But that isn’t a lesson that anyone is claiming this experiment is meant to teach. And that is because the two corns are different and it would not be factual to teach that they are the same.

LikeLike

My point was that we should teach that many different corn hybrids or varieties have many different traits. Yet they all produce corn that is not substantially different.

And I said nothing about “attractive food”. What I said was that “from a consumption standpoint”. Please don’t change my words.

That means to those that are intended to consume them, they are no different. Compositionally, nutritionally, etc.

LikeLike

I think kids know that corn is corn. The Corn Experiment is not designed to teach kids about GMOs or corn. It’s designed to teach them about methodology and it’s designed to determine whether or not wild animals prefer GMO or non-GMO corn when presented a choice.

It will inadvertently teach some kids that GMO corn and non-GMO corn are the same (because animals eat both) The inadvertent lesson is a false lesson. The corns aren’t the same. You seem to be suggesting that teaching kids that the corns are the same is a good teaching goal.

“That means to those that are intended to consume them, they are no different. Compositionally, nutritionally, etc.”

It’s soylent green! LOL But no, the corns aren’t compositionally the same. That’s the whole point of engineering them. And there’s no way to know whether or not they’re nutritionally the same without doing analysis.

LikeLike

Actually, this gmo corn experiment wasn’t meant to teach kids anything at all.

But to this point…

Actually, two decades worth of science has shown us they are. And THAT was the whole point of engineering them…. to engineer crops that are easier to produce without any real impact to the end product.

And of course there’s no way to know if they’re nutritionally the same without analysis. That’s why analysis is required and done.

LikeLike

Like I said – off topic. And the claim has been made that this experiment helps teach kids “the science”. It does teach them some science. And it also unwittingly teaches some kids some non-science.

LikeLike

I’m not sure it counts if you’re the only one who’s made that claim. And teaching consumers of any age that corn with no appreciable consumer differences aren’t different is about as pro-science as you can get.

Now, if you want to teach kids about crop production techniques, sure… you’re going to want to point out a lot of production differences.

LikeLike

I’m not the one that made the claim. If you go back and read the posts about the experiment then we can talk about that if you want to.

Students aren’t supposed to be advertised to as consumers. That’s my criticism. They’re supposed to be taught critical thinking. This experiment does that, but also does the other. Your statement that “teaching consumers of any age that corn with no appreciable consumer differences aren’t different is about as pro-science as you can get” is not supportable as anything other than an opinion – one held by many Monsanto advocates.

LikeLike

Well, you’re the only one I’ve seen make it…and make it over and over and over…

You’re right. It is just an opinion. It just happens that the opinion is held by every major scientific organization on earth. So….yah….there’s that, I guess.

LikeLike

No scientific organization is saying that teaching consumers that GMO and non-GMO corn aren’t different is pro-science.

LikeLike

Well, actually….yes they are. Virtually all have said the that there is no scientific basis for separating these crops via labeling because the crops are equal from a health & safety standpoint. (a consumption standpoint)

Sounds a bit like they don’t see a need to differentiate them to the consumer….right?

LikeLike

Give me a quote that shows that a scientific organization says that teaching consumers that GMO and non-GMO corn aren’t different is pro-science.

You’re stretching and twisting and trying to make advertising into science.

LikeLike

No… I’m not. How about the AMA,

“There is no scientific justification for special labeling of bioengineered foods, as a class,…..”

Sounds like they see no need to differentiate to the consumer. Wouldn’t you agree?

LikeLike

Can you please link me to the document? Thank you.

But still, no – the quote doesn’t say that it’s scientific to teach consumers that GMO and non-GMO corn aren’t different. It says that foods that contain ingredients from GMOs don’t need to be labelled for any scientific reason. I agree with that at this point in time.

LikeLike

and what does that have to do with the subject at hand? Debating whether kids should be educated to be uncritical consumers of various commercial goods is another topic.

LikeLike

Dear Lisa,

The fundamental result of this experiment is that animals can’t tell the difference between GM corn and non-GM corn. That is because of one or two genes and the proteins these produce, the corn are indistinguishable from each other. Certainly in terms of food safety GMO corn is the same as non-GMO corn.

One of the claims that has been heavily promoted by the likes of Jeffrey Smith of the Maharishi movement and Ronnie Cummins of Organic Consumer Association is that animals can detect the difference between GM and non GM crops and avoid the former. This research completely debunks that claim.

LikeLike

The corn is not indistinguishable – but that doesn’t mean that squirrels won’t eat it. I understand debunking the myth, but I don’t understand teaching kids that the corn is indistinguishable because squirrels can’t tell the difference. That’s not scientific.

LikeLike

The fundamental result of this experiment is that animals can’t tell the difference between GM corn and non-GM corn.

That is what the outcome was.

The reason for this outcome is that “apart from one or two genes and the proteins these produce, the corn are indistinguishable from each other.”

LikeLike

The outcome isn’t available yet. But perhaps you, like myself, speak confidently about what the results will be, based on your own empirical evidence.

I think that you and others here have no problem letting the possible results of this experiment teach a lesson that the creators say they’re not trying to teach. That is: the corns are the same because animals eat both.

I’m not comfortable with unwritten, unspoken messages being given to children in the guise of science education. I’m not making any claim that there’s a nefarious purpose here – but I pointed to this fault early on, and it was ignored.

So now I’m stating my opinion that the experiment was a wasted opportunity to teach about GMOs. Debunking a myth is good, but the lesson needs to be carefully presented to avoid teaching kids a scientific falsity. There’s no part of the experiment that teaches the difference that you mention.

LikeLike

Hi Lisa,

Do you have any suggestions for how this project could have been improved?

a) from the perspective of teaching kids how scientific research is done, and

b) from the perspective of learning about differences between foods made using different methods

Regarding “unwritten and unspoken messages”, is there an important message that that was missing? Note that the study was about dietary preferences of squirrels, not human food safety, nutrition, or dietary preferences. The latter three factors would have been much harder to study in a school experiment, or even in a professional lab.

My slight reservation about the study is that it was not a question that most experimental scientists would find interesting enough to be worth answering — but maybe a discussion of the most relevant question may also have taken place within the classrooms. Nevertheless, I’m still looking forward to seeing the final paper when it’s published!

Hats off to Karl and his colleagues for organizing this project!

Finally, in my opinion, we already have far too many squirrels, and leaving corn outside tends to attract other vermin, such as as rats, mice and deer. ;~)

LikeLike

Hi Peter,

I think this experiment can offer a good lesson in how scientific research is done. My criticism is that without a comprehensive context, there’s an unwitting lesson that the GMO and non-GMO corns are the same. For young kids especially, if two corns look the same and are both eaten by wild animals, the conclusion will be that the corns are the same. We don’t want kids to learn that erroneous lesson. We just want to teach them how to do scientific experiments and draw scientific conclusions.

The reason we’re putting out two dissimilar corns is to learn whether or not wild animals differentiate. Why would we expect animals to differentiate if the corns are the same? We want to stress that the corns aren’t the same in order to help explain why we’re doing the experiment. We also should note that squirrels have been known to eat corn, and that’s why we’re putting out both non-GMO and GMO corns. Really, we could just put out GMO corn and see if it gets eaten, but we’re trying to be scientific. We just have to be careful to make sure that we have a discussion about what the experiment does and doesn’t do.

Wild animals’ preference or lack of preference provides no basis for any conclusions about either corn. And that is something that should be discussed after the results are tallied in order to avoid having kids draw their own possibly erroneous conclusions.

Young children need to understand that wild animals don’t have any special ability to discern any particular properties that might protect them or guide them to always eat healthy nutritious food only, and avoid harmful or non-nutritious food.

Science teachers have lesson plans available to them on many different topics. This experiment could be incorporated into a lesson on research methods, and tied to lessons that illustrate how genetic engineering is used to modify crops.

I didn’t make any suggestion that the experiment should be about food safety, nutrition, etc. In fact, I think what I’ve tried to say is that it should be made clear that no conclusions about food safety or nutrition can be drawn from this experiment.

I agree it’s a mistake to feed squirrels and deer, etc. Especially corn, which as you probably know, can harbor toxic mold that can kill squirrels. And feeding deer corn in winter can kill them (enterotoxemia) So those might be important things to discuss with kids too. We don’t want to encourage them to put inappropriate foods out in their backyards.

“we already have far too many squirrels,”

Or too many humans that don’t eat squirrels? 🙂

LikeLike

Hi Peter – I replied to you last night but today my comment does not appear. I know sometimes funky things happen, so I’m waiting to see if it reappears. I don’t know how to contact the moderator and I don’t want to re-post until I find out what’s wrong. Thanks!

Moderator: ok to delete this comment if earlier reply shows up. Thank you!

LikeLike

Hi Peter,

I think this experiment can offer a good lesson in how scientific research is done. My criticism is that without a comprehensive context, there’s an unwitting lesson that the GMO and non-GMO corns are the same. For young kids especially, if two corns look the same and are both eaten by wild animals, the conclusion will be that the corns are the same. We don’t want kids to learn that erroneous lesson. We just want to teach them how to do scientific experiments and draw scientific conclusions.

The reason we’re putting out two dissimilar corns is to learn whether or not wild animals differentiate. Why would we expect animals to differentiate if the corns are the same? We want to stress that the corns aren’t the same in order to help explain why we’re doing the experiment. We should also note that squirrels have been known to eat corn, and that’s why we’re putting out both non-GMO and GMO corns. Really, we could just put out GMO corn and see if it gets eaten, but we want to make a scientific comparison.

Wild animals’ preference or lack of preference provides no basis for any conclusions about either corn. And that is something that should be discussed after the results are tallied in order to avoid having kids draw their own possibly erroneous conclusions.

Young children need to understand that wild animals don’t have any special ability to discern any particular properties that might protect them or guide them to always eat more nutritious food, or avoid harmful non-nutritious food.

Science teachers have lesson plans available to them on many different topics. This experiment could be incorporated into a lesson on research methods, and tied to lessons that illustrate how genetic engineering is used to modify crops. Discussions should include what the experiment does and doesn’t accomplish.

I didn’t make any suggestion that the experiment should be about food safety, nutrition, etc. In fact, I think what I’ve tried to say is that it should be made clear that no conclusions about food safety or nutrition can be drawn from this experiment.

I agree it’s a mistake to feed squirrels and deer, etc. Especially corn, which can harbor toxic mold that can kill squirrels. And feeding corn to deer in winter can kill them (enterotoxemia). So those might be important things to discuss with kids too. We don’t want to encourage them to put inappropriate foods out in their backyards.

“we already have far too many squirrels,”

Or too many humans that don’t eat squirrels? 🙂

LikeLike

Enough of the information has been presented to suggest there is no large difference. Indeed there is no a priori reason why there should be a difference.

If this was the only data available about the composition of GM corn, you would have a point. However, there is oodles (that is a scientific term often used in my lab) of other data out there showing that apart from the small number of genes added and their proteins, there is no difference between the two corn lines.

If you were ever involved in scientific outreach to children you would know that it doesn’t work like this. Children are often far more interested in the process than the results of an experiment. They have nothing vested in the results, so usually don’t care which way they go.

I am guessing here that the main audience for messages about GMOs here were not children. The main messages for children are that science can be fun and interactive. Also messages about running fair tests.

So what would you come up with as an excellent opportunity to teach children about GMOs?

LikeLike

“…there is no a priori reason why there should be a difference.”

exactly

“…apart from the small number of genes added and their proteins, there is no difference between the two corn lines.”

The corns aren’t the same. The degree to which they’re different and the evidence we have to support that is a separate topic. The main difference is that the GMO corn is engineered to carry traits that strongly differentiate it from the non-GMO corn. (pest-resistance, pesticide-tolerance) The whole purpose of engineering is to create something different from its parent. To educate kids that GMO corn and non-GMO corn are the same would be wrong, so we have to be careful that we don’t do that by leaving any important information out of this lesson.

Based on my reading of the experiment, there are no intentional messages about GMOs for anyone who’s taking part – except perhaps that wild animals will eat them. But the unintentional message may be that GMO and non-GMO corn is the same.

The fun and educational part of this experiment is the process: set-up. observation and recording, blinding, etc. Kids will learn how to conduct such an experiment, and a teacher could challenge them to think up other kinds of experiments following the protocol they used in the Corn Experiment. But the results and conclusions will also determine what the kids learn. What conclusions can be drawn from each possible result? We need to discuss with kids what the experiment does and doesn’t do.

There are too many variables with wild animals in an open environment. That discussion should be included, along with one about the real differences between the two corns and why animals might show a preference, or no preference; and what that might imply. Kids need to be taught that the preferences of wild animals says nothing about the corn. The corn might appeal to wild animals for any number of reasons, and might be unappealing to them for just as many. Wild animals don’t have some magic wisdom when it comes to choosing what food they eat. For example, squirrels like corn, but can be sickened by mycotoxins. Also, feeding corn to deer in winter can kill them. Animals will even eat poisoned food if it appeals to their smell and taste.

The couching of conclusions will determine whether or not this experiment helps the kids learn science, or instead encourages them to accept unexamined, unwitting lessons.

And my criticism may be pre-mature, since the research hasn’t been written up. Perhaps Karl will discuss these various shortcomings in his paper.

LikeLike

Hi Chris – I replied to you last night but today my comment does not appear. I know sometimes funky things happen, so I’m waiting to see if it reappears. I don’t know how to contact the moderator and I don’t want to re-post until I find out what’s wrong. Thanks!

Moderator: ok to delete this comment if earlier reply shows up. Thank you!

LikeLike

Chris,

“…there is no a priori reason why there should be a difference.”

exactly

“…apart from the small number of genes added and their proteins, there is no difference between the two corn lines.”