I’m excited to announce today that our first Citizen Science experiment, the “GMO Corn Experiment” is entering its final stage. It has been a long time coming, and I know each and every one of our participants have been waiting to hear the news about our results. I have a lot of things to tell you about in this update, and I’m happy to say that while we encountered some issues with analyzing all the voluminous data that our citizen scientists contributed, we have our results and are preparing them for publication. Along with this update, we want to make sure that every one of our citizen scientists gets a chance to get credit in the final paper.

I’m going to tell you a story spanning the beginning of the experiment right up to today. So to make sure everyone hears the news and gets the takeaways, here is where we are. The analysis of the data from the GMO Corn Experiment is complete, and we are preparing our study for publication. We encountered many difficulties when it came to analyzing all the data submitted to the experiment, but we worked through them and have some clear results that we presented at a scientific conference to get feedback from fellow scientists. We have verified the genetic identity of the ears of corn used in the experiment, and confirmed that they are equivalent in composition. We are sending out a survey to our Citizen Scientists so we can credit them in the paper, and when the paper is submitted we will hold a live broadcast announcement and release some of the results and award prizes to some of our participants who have completed our survey by August 25. Want to know all the details? Read on!

On data and difficulties

Several years ago, when I initially envisioned this project, I thought it would be nice to have 30, 50, or maybe even 100 experiments. That would give us some good numbers to get a satisfying conclusion. As we prepared to announce the project in late 2015, we were going with that plan. Long before the public announcement of the experiment, I requested ears of corn from Monsanto that we could use to test the claim that wild animals would avoid genetically engineered corn, and they agreed to grow two plots of corn in Hawaii and ship the ears to us. As we prepared for that public announcement, I got an email from Monsanto saying that they harvested 3,000 ears from each plot, and wanted to know how many I wanted. Hmm, how about all of them? 100 experiments turned into 2,000 potential experiments in 1,000 kits, thanks to our enormously successful fundraiser. If some data is good, more is better, right?

A year later, we had hundreds of completed experiments, and about 2,000 observations for us to go through. (Well, for me to go through!) As exciting as it was, this was a daunting task. When planning the experiment, we considered all kinds of ways that our citizen scientists could enter their data, and decided that sending photos would be the best way since we could always refer back to them if there was any confusion.

But analyzing images presented its own problems: how do we make sure that the numbers would be reliable and repeatable? The first thing we tried was to analyze the images based on color. The yellow maize kernels have a specific color, and the images can be analyzed to count up the pixels showing how much of the corn is left on either side of the image. By converting the images into false colors it would be just a matter of adding up pixels. Not only would it be repeatable but it would be done entirely without human judgements and whatever biases might be there. Reliable.

We knew that not all of the images would fit this kind of analysis. Some were blurry or taken at a distance, but if enough experiments made the cut we could use those to make our conclusions. It failed. There was simply too much variation in angles, distances, camera types and more to get good data out of this, as Kevin explained in an update he included in his podcast, Talking Biotech. It would be an easy thing to do if this experiment was done in a lab with a solid black background and a precisely positioned camera, but out in the wild as it were, we needed to find a better way.

Settling the score

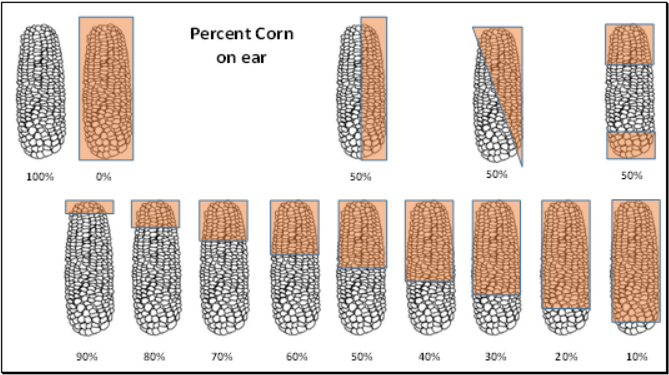

As plant scientists, we went back to our roots with phenotyping. Plant biologists walk through fields rating plant phenotypes on number scales, so we applied that approach to the images. Anastasia Bodnar created a scale, and Kevin Folta gathered a group of volunteers to train and “score” the ears from 0% to 100% with that scale.

There was no need to have them score images that showed no consumption – or even complete consumption of the corn, so I sorted every experiment into one of three bins as to whether no corn was consumed, some of one or both of the ears were consumed, or both of the ears were fully consumed. Since a lot of time elapsed during the first analysis, we scooped up any more experiments completed on the website after our July deadline. By February they were all sorted, annotated, and ready for Kevin’s scoring team. They hammered through all the images and Kevin scanned their hard-copy data sheets so we could enter them into our spreadsheet.

Next came the careful process of checking the handwriting to make sure no 4s looked like 9s, and that the team followed the directions. I searched for individual bias (e.g. did person #3 tend to rate ears as higher or lower than the average?) and the variation was really low between each person. The fantastic thing about this data was that if the ear actually had 75% of the corn remaining, about half of the team put down 70%, and the other half, 80%, giving us an average that would be very close to the real value. Take one or two team members out and the data hardly changed at all.

Repeatable. But was it reliable? How could I tell that no one in the review team was fudging their numbers to prefer one result over another? They were all blinded. They had no idea which ears were GMO and which were non-GMO.

The blinded leading the blinded

Meanwhile, I sent of random samples of the GMO and non-GMO maize kernels that were collected at the start of the project to be analyzed for purity and composition. We needed to make sure that there wasn’t significant cross-pollination between the two plots that could erode our ability to draw conclusions from this experiment. Moreover, we needed to verify, independently, that all of the genetically engineered traits were present in the GMO variety as promised.

There were supposed to be six different Bt traits and two herbicide-tolerance traits to consider, and if it is true that just one of them made wild animals skittish they all needed to be there. We also needed to make sure that Monsanto sent us comparable varieties of corn. If one had less protein or more starch than the other, that could confound our experiment. The tests came back and showed us that there was no evidence of cross-pollination between the plots, all of the traits were where they needed to be, and the compositions of each variety were the same. When the composition samples were sent off, they were assigned random numbers so the testing lab would not know which was which.

The next step, this spring, was to hand off the data to our statistician, Bill Price, who also joined the project. Bill developed some statistical models to analyze the data that came from Kevin’s team. I assigned new numbers to the genotypes in our data (based on the same random numbers I used for the composition analyses) so that Bill could focus on the data and not think about which one was which. He knew from his experience that even “A” and “B” carried meaning so he wanted random numbers. He got “253297” and “442392”. Can you tell which was which? (At the time of writing even I have to go check the spreadsheet to know.)

Why all the layers of “blinding?” Science is the search for empirical truth – knowledge that can be tested and verified through experimentation. Nature does not care what we believe – it operates the way it will – and our task as scientists is to determine the facts as carefully as we can. Human minds are tricky things, though, and we introduce subtle biases – sometimes without knowing it. Good scientists are committed to determining the truth no matter what their prior beliefs are. Doing experiments blinded ensures that subtle biases cannot creep into the experiment based on how we think the experiment should turn out. We also blinded our participants for the same reason. These details make the results more trustworthy for everyone involved – more reliable – and this is a standard that we hope will be adopted by more scientists on all sides of the biotechnology issue.

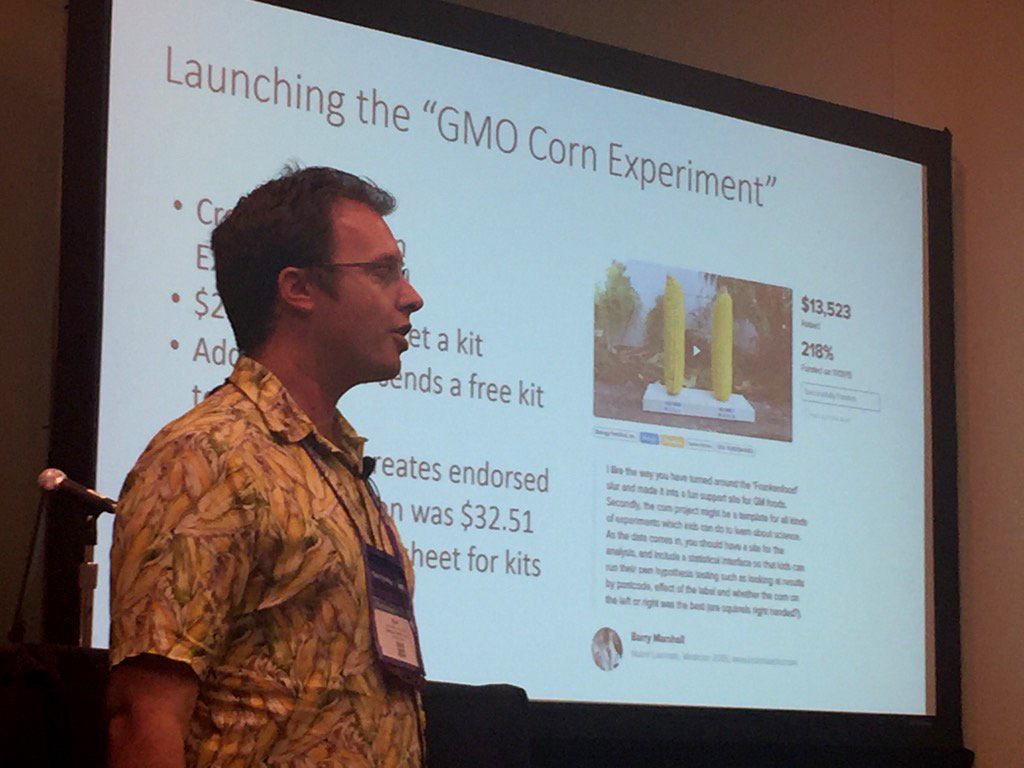

Presenting to peers

In June, we had our first opportunity to present our results to the scientific community. I gave a talk at the Plant Biology 2017 conference organized by the American Society of Plant Biologists. The conference was held in Honolulu, and brought scientists from around the country and from across the Pacific to learn about and discuss each others research with talks, poster presentations, and social events. I also organized a science communication workshop at the beginning of the conference. Presenting new research at conferences is an important step on the path to publication because it allows your fellow scientists an opportunity to ask questions, propose analyses you haven’t thought of, and generate a little buzz in the community as well.

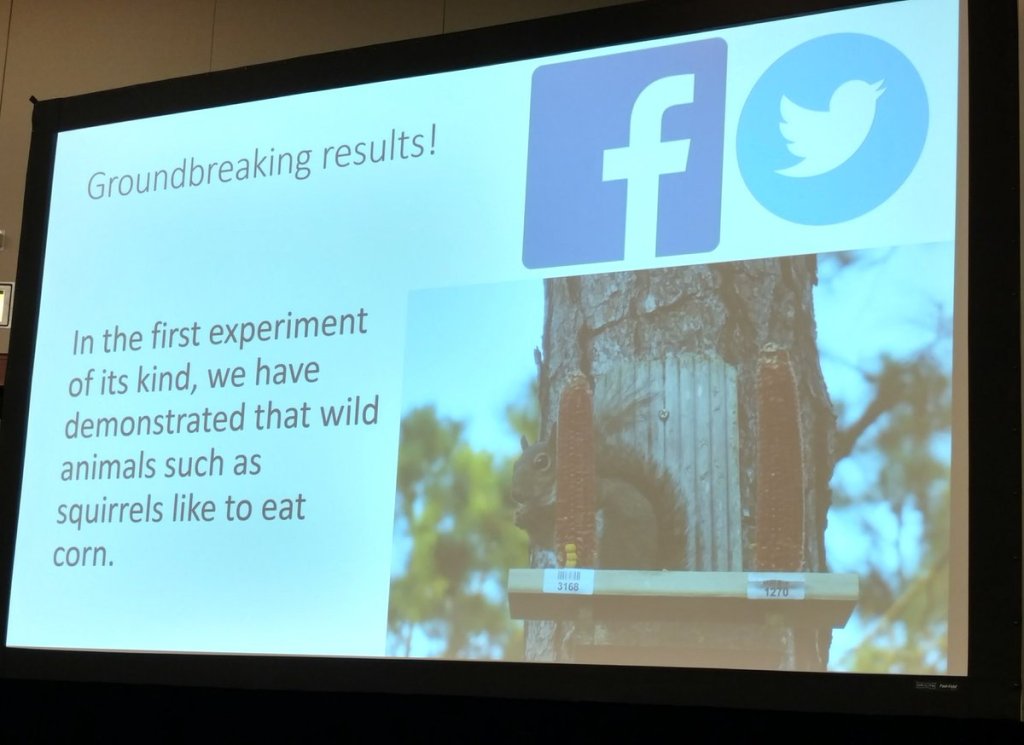

It can also be a bit of fun. I’ve presented on my thesis research at a maize genetics conference before – the hardest, most nerve-wracking presentation I’ve ever given in my life. But standing in a room of experts, once you realize that you’re the expert on your own research it gets a lot easier. Now add the fact that we’ve got a fun story involving public questions and controversy, Nobel Laureates, funny wild animals, excited kids, and the biggest acknowledgements slide that you’ve probably ever seen. It was a blast! I filmed the talk, so don’t worry – you’ll get to see it. If you were paying attention to our Twitter feeds you may have seen some shots of a slide I prepared for the inevitable news leaks coming out of the conference. I saw cell phone cameras focusing during our big data slides, so I was ready with our social-media-friendly slide right after that. Are you ready?

Boom. Controversial, I know. The scientists in attendance were in good humor with this, so I proceeded to my next, and most important slide. I wasn’t just there to share our research – I had another agenda: to convince my colleagues that research can also be outreach. Afterward, several people told me that this was the most interesting part. We tend to think of research as discovering knowledge, and outreach as communicating knowledge. I think differently. I think that good research can also be designed as outreach, to both discover and communicate knowledge at the same time. And I believe that we can take this model and apply it to even bigger questions about food, biotechnology, and agriculture. Together, we can change the way that science is done and create a better informed society.

Paper the town

We’re getting down to the last phase of our project. With our results in-hand, and our conference presentation and discussions behind us, we’re busy preparing our paper to submit it to a peer-reviewed journal. For those who are not familiar with this step, we’re carefully writing up the methods, formatting the data, and making decisions on how to best present our results so that everyone can understand them, and so that other scientists could replicate them. There’s more data than what I presented in my talk, including validating our methodology, and so our challenge now is fitting it all together as a cohesive article. There are so many ways to present the data, so we’re choosing what tables, charts, and graphics communicate the most information.

The ears of corn we used for the experiment were donated by Monsanto, and we signed a Material Transfer Agreement with them, which allowed us to conduct our experiments with their corn, and laid out everyone’s rights. As part of that agreement, we will be sharing our results and our draft of the paper with them prior to submitting it to a peer-reviewed journal.

This is a very standard practice when scientists are studying patented material owned by someone else, and it ensures that we can publish our results – whatever we find – and they get a heads-up on it before we go to publication. Their scientists may even make suggestions such as how to describe their maize varieties or suggest analyses, but we alone have the power to do anything based on those suggestions. To show everyone how this process works, when all is said and done we will show you what we sent them, what they sent back, and any changes we made based on that information.

Then, the paper goes off to a scientific journal to undergo peer review, where anonymous scientists will pick it apart, rate the quality, novelty, newsworthiness, etc. They may recommend publication, revision, or rejection. We might have to make changes and send it back, and we’ll keep you updated on the process when it happens. When we get it published later this year, we’ll have so many stories to tell about this project. It will make a splash!

Credit where credit is due

We can’t take all the credit – because so much of the success of this experiment is due to the work of our Citizen Scientists, donors, and supporters. That’s why we’re taking special care to make sure that everyone involved, from donors to participants, get credit for their contributions.

That’s right, if you were a part of this project, YOU WILL GET YOUR NAME IN OUR PAPER! Although our list is huge, online publishing has no practical size limits so you will get to see your name preserved permanently as part of the scientific record in a supplemental acknowledgements section. To make sure that each and every one of you get credited the way you want, we are sending out a survey over the next couple days to our study participants. Look for it, and please fill it out right away! If you do not receive it by Monday, please contact us and we will make sure that you get it.

Remember when you signed up for the experiment, we agreed to keep your personal information private. So in order to credit you we need your permission – and the great part of this is if you want to highlight the contributions of your K-12 research team, you can choose how to credit them. If you want to remain anonymous, you can choose that option as well. (Experiment.com donors who did not participate in the experiment do not need to fill out this survey as their contribution is already public and will be included in our acknowledgements.) As an extra incentive for finishing our survey, we’re going to award some prizes for participation.

Did you say awards? Prizes?

Yes I did! Remember how I said that I read through over 2,000 observations? How I sifted through hundreds of experiments, and all the images they contained? I could see all the work you put into these experiments. I could sense the enthusiasm, the creativity, the frustration, and the satisfaction. I remember one citizen science team that kept repeating their experiment over and over again, taking notes saying that no animals touched the corn. Diligently, for two weeks, taking photos, resetting the experiment, and gathering weather data. Then came the day that they finally attracted the attention of wild animals, corn was getting eaten and exclamation points were everywhere. I half jumped out of my seat! That kind of dedication deserves recognition.

More teams impressed me with their detail-oriented approach – taking careful and comprehensive observations. Others took incredible and sometimes hilarious photos. There was some good humor involved in some of the experimental data – “kids” in the list of wild animals active in the area, signs posted in the background of their experiments, and prosaic observations. I could see some future scientists in there. We need an award ceremony.

When you get the survey, fill it out and you are entered to win one of several awards for your participation, including several randomly-selected prizes. Fill it out by August 25th!

When we submit our paper we will hold a live streamed broadcast to announce the submission, release some of our results to the public, and celebrate everyone’s contributions and announce the awards. Stay tuned, because the most exciting part is yet to come.