A recent paper published in The Bulletin of Insectology claiming that neonicotinoids are the sole cause of CCD has been circulating in the media. The author, Chensheng Lu, has a history of doing research that makes spurious claims about the relationship between CCD and a specific group of pesticides. In this post, I am going to discuss Lu’s research, and use it as a stepping stone to discuss the role that pesticides play in honeybee health.

Why are honeybees exposed to pesticides?

Bees are insects which are raised as livestock, and kept around farms in order to pollinate crops. In order to combat mites which damage adults and spread diseases, beekeepeers use a variety of pesticides. The two most widely used are a pyrethroid called Fluvalinate and an organophosphate called Coumaphos. It is easy to forget that we treat these mites with insecticides, and many popular media reports neglect to mention this completely and instead focus on the agricultural pesticide angle. However, Fluvalinate and Coumaphos are found in virtually all pollen and wax samples. They are frequently found with chlorotalonil, which will synergize the activity of pyrethroids. Coumaphos is the only pesticide found more frequently in non-CCD afflicted colonies. These pesticides are an important part of the honeybee health story.

In 2010, a team lead by Christopher Mullin did a broad survey of agrochemicals found in American beehives that is (to my knowledge) the only wide-scale survey of agrochemicals found in American beehives. The dataset they generated is so immense that it is impossible to properly discuss in a single blog post, so I will need to relegate myself to a very narrow discussion. In general, pesticide levels were well below the lethal limit (Mullin et. al, 2010). It’s important to note that there were occasional exceptions where some insecticides, namely a variety of pyrethroids, organophosphates and the neonicotinoid imidacloprid, did approach lethal limits (Mullin et. al, 2010). Because Lu’s paper focuses on neonicotinoids I will focus the majority of my discussion on this group of pesticides. I will, however, return to discuss the broader implications of Mullin’s work.

How do neonicotinoids affect bees?

Honeybees are in a unique position in the world of insects which are important to agriculture. They’re social insects who must leave their home, find food by recognizing specific plants, return to a specific area, and communicate to their nestmates the location of food. In addition to this, there is a division of labor within the nest. Newly hatched bees will care for young, and perform pest control. As they age, they gradually move into a forager type position and guard the nest. This sort of lifestyle takes a lot of brainpower. Thus there is a concern about neurotoxins which affect the behavior of bees.

The question of how toxic a pesticide can be is figured by determining which dose kills 50% of bees in a test group, a dose called the LD50. This dose is figured using individual bees, which is all well and good, but bees are a superorganism and this might not capture effects that effect colony health at lower than lethal levels. You need the superorganism LD50, which isn’t nearly as straightforward due to space limitations and variation between colonies.

Because bees rely on a complex set of behaviors, levels of pesticides that disrupt these behaviors represent a particular concern. This is actually pretty intuitive, and we can draw parallels with alcohol. A lot of important human activities, like driving and social interaction, also depend on complicated behaviors which can be disrupted by neurotoxins well below lethal levels. I like to draw parallels with alcohol, because it’s something everyone will understand. The NSFW website Texts From Last Night compiles textbook humorous examples of human social behavior which have been disrupted by the neurotoxin alcohol. It could be said that bees can potentially become drunk on neonicotinoids.

Neonicotinoids are neurotoxic pesticides which incorporate themselves into plants, and can be found in the pollen and nectar of treated plants. Neonics can be coated on the seed (known as seed treatment) or simply dumped in the soil around the plants (known as drench treatment), or injected right into the plant (usually reserved for ornamental crops). The Xerces Society has a good review on Neonicotinoid concentrations in plant tissues. Concentrations in pollen can vary widely and depends on the crop they’re used on, the application rate, and how the pesticides are applied. Seed treatments, which represent most neonicotinoid use, likely present few problems because these application rates are very low and result in pollen neonic levels of 1-2 ppb. Soil drenches may present problems, because neonic levels can exceed 50 ppb in pollen in some cases. The real problems with neonics lie with ornamental crops because these can have application rates 10 times those used in agriculture, and neonic levels in pollen can reach fatal levels.

Any response to Lu’s study shouldn’t shy away from discussing potential problems with neonicotinoids, however, in various interviews Lu makes it very apparent he thinks neonic seed-treatments are the cause of CCD. He frequently singles out corn pollen in his interviews, and claims (but never demonstrates) that the corn syrup beekeepers use is contaminated with the insecticides. He also frequently claims in these interviews that the levels he exposes bees to are lower than field rates.

Before long, I’ll demonstrate that Lu’s claims are false. But first things first…

How did Lu conduct his experiment?

Lu’s experimental design was a bit complicated. Lu began with 18 colonies, and split them into two groups of nine. One group of colonies was fed sucrose syrup; the other, High Fructose Corn Syrup (HFCS). These groups were subdivided into groups of three, and fed with one of two neonicotinoid pesticides (Imidacloprid or Clothiandin); another was fed only syrup. In essence, he had 3 pairs of triads fed either different syrup or different pesticides. One representative from each pair of triads was shuttled to one of three apiary locations.

Lu’s experimental design was a bit complicated. Lu began with 18 colonies, and split them into two groups of nine. One group of colonies was fed sucrose syrup; the other, High Fructose Corn Syrup (HFCS). These groups were subdivided into groups of three, and fed with one of two neonicotinoid pesticides (Imidacloprid or Clothiandin); another was fed only syrup. In essence, he had 3 pairs of triads fed either different syrup or different pesticides. One representative from each pair of triads was shuttled to one of three apiary locations.

He divided three of these groups among three sites, let them forage for the summer and began to feed the treatment groups pesticides once they were ready to overwinter. He treated the colonies at .74 ng/bee/day for the pesticide treated groups. Treatment time was 13 weeks during the overwintering stage.

If we take Lu’s interpretations at face value, he believes that he managed to replicate CCD because his neonicotinoid treated hives shrunk during the winter, without dead bees accumulating at the bottom of the hive. According to Lu’s analysis of his team’s results:

One of the defining symptomatic observations of CCD colonies is the emptiness of hives in which the amount of dead bees found inside the hives do not account for the total numbers of bees present prior to winter when they were alive. On the contrary, when hives die in the winter due to pathogen infection, like the only control colony that died in the present study, tens of thousands of dead bees are typically found inside the hives. The absence of dead bees in the neonicotinoid-treated colonies is remarkable and consistent with CCD symptoms.

Did Lu manage to replicate CCD using neonicotinoid treatments?

Unfortunately there’s a lot of areas where Lu went wrong, both in his methods and in his interpretation of his results. His main finding is that he believes that he replicated CCD, and this has been widely reported in the media. So let’s tackle his take-home message first, before moving onto the nitty-gritty details.

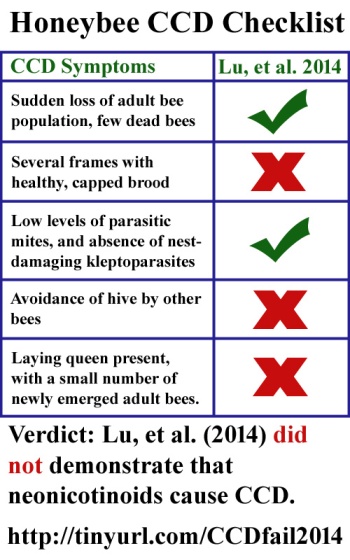

Remember that Colony Collapse Disorder is a very specific set of symptoms, and that dead and abandoned hives aren’t neccessarily afflicted with CCD. In general, beekeepers lose about 1/3rd of their hives to things like parasites, pathogens, pesticide poisoning, and CCD. CCD accounts of about 1/3rd of the lost hives, or about 1/9 of the total colonies. This is how the USDA defines CCD:

- Sudden loss of the adult bee populations with very few bees found near the dead colonies.

- Several frames with healthy, capped brood

- Low levels of parasitic mites, and absence of nest-damaging kleptoparasites (e.g. wax moths, hive beetles).

- Avoidance of hive by other bees

- Laying queen present, with a small number of newly emerged adult bees.

So…did Lu recreate CCD as he claimed?

No.

At best, Lu’s results in both his 2012 and 2014 papers can be interpreted to demonstrate that honeybees can have trouble overwintering if fed high amounts of neonicotinoids. This point is well taken, but his claim of demonstrating that neonicotinoids are the cause of CCD is a giant overstep in interpretation.

At best, Lu’s results in both his 2012 and 2014 papers can be interpreted to demonstrate that honeybees can have trouble overwintering if fed high amounts of neonicotinoids. This point is well taken, but his claim of demonstrating that neonicotinoids are the cause of CCD is a giant overstep in interpretation.

Lu did report declines in levels of bees which seem to indicate that insecticides made a difference in adult survival during overwintering. However, Lu also reported that of the honeybee hives which survived the insecticide treatment, all had either no queen or no brood. Hives afflicted with CCD must have both queens and brood. He did, to his credit, report low levels of mites and didn’t mention the kleptoparasites so he’s got that working in his favor. However, the symptoms he reported did not match the case definition CCD. The biggest problem with Lu’s interpretation of his data is that he conflates hive abandonment with CCD.

To understand this result, you need to know a little bit about social insect biology. While hive abandonment is a part of CCD, hive abandonment is not unique to CCD. Hive abandonment in social insects is, in essence, suicidal quarantine. They leave the hive in order to prevent spread of disease to nestmates. Hive abandonment can be triggered by pathogens (e.g. Malpighamoeba mellificae), sublethal doses of toxic chemicals other than neonicotinoids (e.g. pyrethroids), even CO2 narcosis (Evans & Schwarz, 2011, vanDame et. al, 2009, Cox & William, 1987, Rueppell et. al, 2010). Hive abandonment is a generalized response to sickness in social insects, and by itself does not indicate CCD.

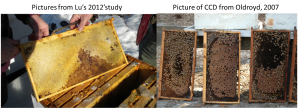

The picture in the next paragraph allows a side-by-side comparison between Lu’s hives and a hive which has CCD. Suffice to say, Lu’s pictures are very different from those which have been affected by CCD. There are very important differences between the colonies Lu poisoned with insecticide and those which have been affected by CCD. Despite these differences, Lu claims he has replicated CCD. However, his data demonstrates that he did not replicate CCD.

What did Lu do wrong?

Lu’s tests were not precisely performed, and suffered from a small sample size of 18 hives. In essence, he had six treatment regimes but treated them as three by merging the two different types of separately prepared syrup for his analysis. While this might not have had a huge effect, it probably still introduced some variability. Many other variables were completely unaccounted for. For example, it wasn’t discussed if the dead colonies were spread evenly through the sites, or if they were found in the same site. Instead of measuring the temperature at his colonies, he instead looked at NOAA measurements taken at the local airport. I could discuss these problems in detail, but I think the problem which is most worthy of discussion is the fact that Lu is claiming that this experiment demonstrates that neonicotinoids are responsible for wide-scale problems with honeybee health.

Lu’s experiment was a no-choice feeding test, which is kind of similar to a cell-culture test. The tests occur in an environment which may not match real-world scenarios. Basically, he dosed the bees with neonicotinoids by pumping them straight into the colony in corn syrup which they’ll consume because it’s the closest food source.

No-choice tests don’t take into account the fact that bees will feed preferentially from different sources in real-world situations. So while levels of neonicotinoids in pollen from seed-treated crops will vary from 1 ppb to more than 10 ppb, the levels they actually eat are very different for a number of reasons. At a certain level of contamination (~20 ppb in corn syrup), it’s likely they’ll avoid pesticide contaminated pollen (Blacquiere et. al, 2012). They’ll also gather pollen from uncontaminated crops, and mix it in with the contaminated pollen. So neonicotinoid residues in pollen don’t necessarily reflect what they are in bee colonies.

Doses in honey aren’t nearly as straightforward because there’s scarce data for the United States. However, they appear to be in the neighborhood of 1 ppb in other countries (Blacquiere et. al, 2012). Based on levels found in actual bee colonies a field-realistic dose of neonicotinoid in pollen is probably 1-3 ppb, although significantly higher levels can occur (Mullin et. al, 2010, Blacquiere et. al 2012). However, the neonicotinoids are not found ubiquitously in bee pollen. Mullin et. al 2010, for example, found imidacloprid in less than 3% of pollen samples taken from colonies. Lu treated his bees at 136 ug/l of syrup. Assuming a liter of syrup weighs 1375 grams (based on density of HFCS), his syrup contained 99 ug/kg of the neonicotinoid insecticides, which is a 5x higher dose than even the most contaminated pollen bees are likely to encounter in crops with seeds treated as per the pesticide label. More importantly, it’s also a dose 33-fold higher than the neonicotinoid contaminated pollen which is found in typical honeybee colonies. Bottom line: he appears to have overdosed the colonies compared to what they are encountering in the real world.

There are also some severe issues with his dosing schedule. He claimed that he dosed the bees at .74 ng/bee/day, but the paper seems to indicate that he did not change the dosing schedule as the populations declined during the winter. As the bees declined, the dosage per bee increased. He also neglected to measure the bee populations to determine his initial dose. He merely assumed a starting point of 50,000 bees.

Lu does not cite literature which undermine his Hypothesis

Just as telling as Lu’s misinterpretation of his results, and his questionable methods, are Lu’s citations in the article. He cites a handful of popular media reports, which is unusual but not completely unheard of in the scientific literature. However, there are a lot of citations which should be there but aren’t. For instance, there is no discussion of field-realistic levels of agrochemicals found in honeybee colonies. This information can be easily found in open-access journals (Mullin et. al 2010, Blacquiere et. al, 2012). Perhaps the most damning omission from Lu’s citation list are field trials. There have been many field trials which have attempted to look at the effects of neonicotinoids on bees (Pohorecka et. al, 2012, Schmuck et. al 2012, Cutler & Scott-Dupree, 2007, Nguyen et. al, 2009, just to name a few). While they all represent different scales, and while each has its own quirks and intricacies, they overwhelmingly indicate that neonicotinoids do not affect colony health under field conditions and proper use. These are high profile papers which are easy to find and which cast doubt on Lu’s claims, but Lu makes no attempt to reconcile his results with these tests.

Pesticides and Bees: the Bigger Picture

The relationship between pesticides and bees is extremely complex, and would probably take several dozen posts to fully discuss. Earlier, I mentioned detections of specific pesticides in Mullin, 2010 and I’d like to return to that point. This study reported a high amounts of imidacloprid in one sample, but neonicotinoids were found in less than 10% of the samples tested. When they were found, they were far below the levels which caused harm (Blacquiere et. al, 2012). While neonicotinoids didn’t appear in the concentrations or frequency which could cause harm, the team found that multiple types of pesticides (mainly pyrethroids and organophosphates) can approach LD50 levels in honeybee colonies. We’d reasonably expect sublethal effects in the colonies where they reach these levels. Often, these are found with fungicides which will synergize their activities by blocking the enzymes bees use to detoxify them. The effects of the miticides on bees are similarly in question, given their frequent and high detections in colonies. A lot of pesticides are found in honeybee colonies and based on pesticide survey data the USDA actually suggests that pyrethroid insecticides are a higher risk to honeybee colonies than are neonicotinoids. Ironically, Lu cited this report but did not discuss this conflict between his data and the views of the larger community.

Neonicotinoids are a small subsection of the pesticide story. Pesticides are a very small part of the CCD story, and are a small part of the overall honeybee health story. Landscape changes due to agricultural intensification and urbanization can change the diversity of the available food, which can change the physiological status of the bees. Bees are kept in crowded, stressed conditions and are driven cross-country where they will come into contact with other bees. This creates an opportunity for rapid disease transmission to new populations, and creates conditions which favors strains of existing diseases evolving to become more virulent. Pesticides act as a stressor on top of all these. Because there are so many interacting factors, it is generally believed that there is no ‘One True Cause’ of CCD.

The story of CCD is a serious one, and it should be discussed in the public sphere. What disturbs me about this discussion is that the Lu paper discussed above has managed to go viral among the media outlets not because it’s quality science but because it fits an anti-pesticide narrative that the media has become increasingly comfortable with. The standard neonicotinoid narrative is convenient because it makes the situation simpler…a single problem, and a single solution which involves banning a single substance. However the real pesticide story involves dozens of compounds with wildly different uses, which interact with biological and environmental factors which are still poorly understood at best. The neonicotinoid story is just as complex because they likely don’t cause problems in all crops, but issues with proper use and application rates still need to be sorted out. There’s also a human component in some systems which is never discussed, where neonicotinoids frequently replace pesticides more toxic to people like organophosphates. Unfortunately, Lu’s research does nothing to highlight legitimate issues with these pesticides in particular. The thing that perhaps makes people the most uncomfortable, is that unlike climate change or evolution, the issues discussed here are not a case of settled science and continue to evolve as we better understand these factors.

References:

Lu, Chensheng. Warchol, K. Callahan, R. (2014) Sub-lethal exposure to neonicotinoids impaired honey bees winterization before proceeding to colony collapse disorder. Bulletin of Insectology 67 (1) 125-130

Lu, C. Warchol, K. Callahan, R. (2012) In-situ replication of honey bee colony collapse disorder. Bulletin of Insectology (65) (Online)

Mullin, C. Frazier, M. Frazier, J. Ashcraft, S. Simonds, R. vanEngelsdorp, D. Pettis, J. (2010) High Levels of Miticides and Agrochemicals in North American Apiaries: Implications for Honey Bee Health. PLOS ONE. 5(3)

Blacquiere, T. Smagghe, G. van Gestel, CAM. Mommaerts, V. (2012) Neonicotinoids in bees: a review on concentrations, side-effects and risk assessment. Ecotoxicology. 21: 973-992

Stoner KA, Eitzer BD (2012) Movement of Soil-Applied Imidacloprid and Thiamethoxam into Nectar and Pollen of Squash (Cucurbita pepo). PLoS ONE 7(6): e39114. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039114

Evans JD. Schwarz, RS. (2011) Bees brought to their knees: microbes affecting honey bee health. Trends in Microbiology. 12: 614-620.

van Dame, R. Meled, M. Colin, ME. Belzumces, L. (1995) Alteration of the Homing-Flight in the Honey Bee Apis mellifera Exposed to Sublethal Dose of Deltamethrin. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 14(5): 855-860.

Cox, R. Wilson, W. (1984) Effects of Permethrin on the Behavior of Individually Tagged Honey Bees, Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Environmental Entomology 13(2): 375-378

Rueppell, O. Hayworth, MK. Ross, NP. (2010) Altruistic Self-Removal of Health-Compromised Honey Bee Workers From Their Hive. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 23(7): 1538-1546

Pohorecka, K. Skubida, P. Miszczak, A. Semkiw, P. Sikorski, P. Zagibajlo, K. Teper, D. Zbigniew, K. Skubida, M. Zdanska, D. Bober, A. Residues of Neonicotinoid Insecticides in Bee Collected Plant Materials From Oilseed Rape Crops and Their Effect on Bee Colonies. Journal of Apicultural Science 56(2): 115-134

Schmuck, R. Schoning, R. Stork, A. Schramel, O. (2001) Risk Posed to Honeybees (Apis mellifera, Hymenoptera) by an Imidacloprid Seed Dressing of Sunflowers. Pest Management Science 57(3): 225-238

Cutler, C. Scott-Dupree, C. (2007) Exposure to Clothianidin Seed-Treated Canola Has No Long Term Impact on Honey Bees. Journal of Economic Entomology 100(3): 765-772

Nguyen, BK. Saegerman, C. Pirard, C. Mignin, J. Widart, J. Thirionet, B. Verheggen, F. Berkvens, D. DePauw, E. Haubruge, E. (2009) Does Imidacloprid Seed-Treated Maize Have an Impact on Honey Bee Mortality? Journal of Economic Entomology 102(2): 616-623

USDA (2013) Report on the National Stakeholders Conference on Honey Bee Health. Online.

Oldroyd BP (2007) What’s Killing American Honey Bees? PLoS Biol 5(6): e168. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050168

There are some things I couldn’t squeeze into this post that I wanted to mention as a springboard for further discussion. This post should be read as Part 2 of my post from 2013:

https://biofortified.org/2013/03/colony-collapse-disorder-an-introduction/

1.) The paper I spent most of the time discussing, Mullin et. al 2010, was a very well performed and groundbreaking study in many ways but it left me with a whole host of questions. I’d like to know how in-colony pesticide levels change depending on the crop the bees are pollinating, and how pesticide levels change depending on distance away from pesticide treated crops. This isn’t a criticism because the data Mullin generated needed to be generated before that could even be thought about.

2.) This has been mentioned by Raymond Eckhart in other forums but because Neonics are basically an organophosphate substitute in some cropping systems, I wonder if bees would be worse off if we banned neonics. After all, Mullin’s team found lots of organophosphates in the colonies and those are pretty nasty insecticides.

3.) Lu counted the percentage of frames containing bees, and then used an ANOVA to analyze his data. I talked to Bill Price about this over Twitter, and I’m not sure this is correct. Counting whether or not a frame has bees on it has a binary outcome (bees present or absent), and isn’t normally distributed because of that. An ANOVA is for normally distributed data, and a non-parametric analysis like Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis would probably be more appropriate. In fact, Rueppell et. al 2010 uses either Chi-squared or Fisher’s tests to analyze data that is very similar to what Lu generated.

4.) A second problem with the statistics is that Lu simply analyzes a lot of timepoints. When you analyze a lot of timepoints, you can get a different result just from chance. To eliminate this possibility, data is frequently corrected using a Bonferroni correction which takes this into account. Lu does not mention a Bonferroni correction anywhere in his paper which makes me thing he did not take this into account.

So…more food for thought for those who want to discuss this paper.

LikeLike

Nice try Joe, why don’t you repeat the study and apply all the corrections that you speak about?

LikeLike

That’s an awfully dismissive comment. Joe gave specific reasons and explained why these flaws matter for science. You just said “Nice try” with no details that any of his criticisms were off-base. I think the point is that the study design should have been carefully considered before the study was done, and then the results should have been more carefully scrutinized for whether they confirm or reject the null and alternate hypotheses. Think about that the next time you want to express your disagreement.

LikeLike

There’s no reason I should attempt to replicate every study I’m skeptical about.

Lu did his experiments wrong, he ignored nearly all relevant background information, he incorrectly analyzed his data, he didn’t recreate the condition he claimed he was replicating, and above all he ignored and possibly misrepresented conflicting information.

Replication just simply isn’t a factor here, because most of my criticisms are about real-world relevance, misinterpretation, and overselling.

LikeLike

“In general, beekeepers lose about 1/3rd of their hives to things like parasites, pathogens, pesticide poisoning, and CCD. CCD accounts of about 1/3rd of the lost hives, or about 1/6 of the total colonies. ”

Shouldn’t that be 1/9th of the total colonies?

LikeLike

Yes, Skeptico…it should. Thanks for pointing that out…it’s been corrected.

LikeLike

The result of the 2 years ban in Europe should clarify this hypothesis.

LikeLike

Or generate a new round of excuses.

LikeLike

The place to look at for clarification is going to be the Netherlands this past March they banned all Neonicotinoids for all uses permanently.

LikeLike

I think France also has a similar ban, however they got CCD nonetheless.

LikeLike

I actually think the result of the 2-year neonic ban in Europe will do little to shed light on CCD specifically.

CCD is a specific diagnosis based on a specific set of symptoms. While American scientists were quick to recognize CCD and settle upon a case definition, European scientists have been much slower to do so. In fact the first case of CCD was only published in 2012, and hasn’t been cited by anything in pubmed. It’s clearly there, but Europe has been very slow to study it for reasons I don’t quite understand.

Click to access Dainat%20et%20al%2012-CCD%20in%20Switzerland.pdf

Europe has still had problems with colony losses from other reasons, even in areas where neonics are banned. In the US colony losses have fluctuated without any major changes in neonic use. In fact, there’s even a paper which applies epidemiological criteria to the question and finds no association.

Click to access 2012Cresswell.pdf

Of course, it’s still possible that new data could emerge and fill in some of the gaps mentioned in Cresswell. Specifically, I’d like to see more landscape level studies.

However, from my reading of the literature, I don’t buy a neonic-specific explanation of either CCD or widespread colony losses. CCD is most likely multifactorial, and bees die for a variety of reasons unrelated to pesticides.

Do they play a role? Probably, but it’s likely other pesticides play similar or larger roles. Are neonics the sole reason beekeepers have problems? No, and we shouldn’t pretend they are.

LikeLike

Cresswell study pivots on Cutler & Scott-Dupree 2007 evidence – see below for problems with this being a pivot point.

LikeLike

Actual CCD losses have been declining in recent years. From the 2012-2013 ARS report (http://www.ars.usda.gov/is/br/beelosses/index.htm):

My understanding is that CCD in 2013-2014 was minimal as well. Bee management issues and stress would appear to be more important factors in overall health. Also from this report is a telling clue:

That 20% is important because many of these bee keepers are running 1,000’s, if not 10,000’s of hives in such operations.

LikeLike

Dear Joe

Great article, really well put together. It is indeed important to remember that there are many other agricultural chemicals that may impact on pollinators.

Here are a few observations from a European perspective, bit of a rush so apologise now if not as well referenced as I would like.

CCD – while hives in the EU may occasionally show full CCD symptoms, it does not happen frequently enough for us to consider there to be one specific problem with honeybees. Over here the perception is that hive health has declined and overwintering success is now much poorer than it once was. Hence the question ‘are neonics the cause of CCD’ is of limited interest outside N America.

Other pollinators – it is unlikely that Honeybees here do more than 10% of pollinations, most food and wild flower seed arises from solitary bees, bumblebees, hoverflies, moths, etc. These are the species that we must also consider. Varroa mites, CCD and hive miticides are all irrelevant to most declining pollinator species.

Complexity of causes – there are many severe problems for bees and other pollinators and associated declines, and while wildflower loss is a key factor, insecticides doubtlessly also play a role. The European Food Standards Authority (EFSA) has determined three neonics to be a confirmed high risk for Honeybees. Generally the scientific papers indicate that bumblebees and solitary bees are more sensitive and more vulnerable to neonicotinoid poisoning (they also have a lot of remembering to do).

Key question – the key question is whether the risk posed by pesticides to pollinator populations is ethically acceptable. Part of this question requires an ethical judgement and part is theoretically knowable – do the benefits to humans of using neonics out-weight the costs.

Lu – clearly this work is only relevant to the little Honeybee section of pollination services (and we don’t have lorry loads of professional Honeybees in the EU). The effects of the neonicotinoids on Honeybees in his two papers are interesting, but the dosing rates are indeed far higher than what would be encountered just through pollen and nectar in arable crops. There are however other forms of contact – dust, guttation fluid (Girolami et al. 2009 Translocation of Neonicotinoid Insecticides From Coated Seeds to Seedling Guttation Drops. A Novel Way of Intoxication for Bees) and puddles – and other uses – ornamental and garden – for which there is less research relating to concentrations and exposure, some of which may be close to the levels used by Lu. In addition the potency of neonicotinoids can be higher in products (1000 times in Mesnage et al 2014 Major pesticides are more toxic to human cells than their declared active principles) or when acting in synergy with fungicides (2 to 5 times in Biddinger et al 2013 Comparative Toxicities and Synergism of Apple Orchard Pesticides to Apis mellifera and Osmia cornifrons (Radowszkowski)). Lu’s own theory that the neonics were concentrated into sugar syrup from treated maize crops that was then fed to bees does not appear to be evidenced and indeed sounds unlikely, but it would be interesting to hear from anyone who understands that purification process and could say if the theory is or is not feasible. The EU coverage of Lu’s work has generally been rather cautious http://www.independent.co.uk/environment/nature/new-pesticide-link-to-sudden-decline-in-bee-population-7622263.html

Do neonicotinoids work – we know that pollination services are worth billions, but what are the benefits of neonicotinoids. The US report ‘Heavy Costs’ shows that the evidence from field studies is not conclusive – it is not clear that the value of yield increases is higher than the costs of the insecticides – some of the UK costings indicate that our agriculture may be more profitable without neonics – more on this here – http://www.buglife.org.uk/blog/matt-shardlow-ceo/drugs-neonicotinoids-don%E2%80%99t-work.

Field studies not finding an effect from neonicotinoids – there are several published studies that failed to find an effect in the field, and the best of these do offer reassurance that the impacts of neonicotinoids on honeybees are not instantly disastrous. As you say they do all have some limitations. But for some of them the problems run well beyond limitations. For instance Cutler & Scott-Dupree 2007 is based on a regulatory study that was invalidated by the Canadian authorities. It was considered meaningless because of 1) the small area of treated crop available to the ‘treatment’ hives, 2) the treated crop was also within the foraging range of the ‘control’ hives and 3) the ‘treatment’ and ‘control’ hives were pretty equally contaminated with neonics. You say you name ‘a few’ of the published field studies, but your list is pretty comprehensive!

Interaction – Field studies are hard work and therefore are not readily capable of determining ecosystem wide impacts such as interactions between pesticides or between pesticides and diseases – effects that have been proven in the laboratory – e.g. Doublet et al 2014 Bees under stress. sublethal doses of a neonicotinoid pesticide and pathogens interact to elevate honey bee mortality across the life cycle.

Soil – neonics are surprisingly persistent in arable soils and are water soluble – this background build up may result in higher concentrations in pollen, nectar and water sources inside and outside arable fields. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ps.3836/abstract

You conclude that we should not tackle just one issue or one insecticide group and that is absolutely correct. But neonicotinoids are a significant concern and should be tackled. And I do question your claim that “neonicotinoids frequently replace pesticides” we have generally found that seed treatments are additional. Pyrethroid use has not dropped since the introduction of neonicotinoids. Farmers are taking a belt and braces approach.

Deryn Gilbey seeds and traits manager at Dekalb a majour supplier of Oil seed rape seed said in the Farmers Guardian this week that “the level of yield benefit from neonicotinoids in controlling its aphid vectors is highly questionable. Perhaps this is why there is no sign of any dramatic UK performance increase which could be linked to the introduction of neonicotinoids in the recent official yield record”.

Hope this adds some additional dimensions to the concerns about neonicotinoids and food production.

Cheers

Matt

LikeLike

Matt – I think it is important to highlight the entire quote attributed to Deryn Gilby:

“About two-thirds of the annual OSR crop is typically affected by the cabbage stem flea beetle and flea beetle pests the seed treatment is primarily targeted at.

“We know levels of infestation and crop damage vary widely from season to season, farm to farm and field to field.

“Equally, regardless of the theoretical losses from turnip yellows virus (TuYV), the level of yield benefit from neonicotinoids in controlling its aphid vectors is highly questionable.

“Perhaps this is why there is no sign of any dramatic UK performance increase which could be linked to the introduction of neonicotinoids in the recent official yield record (see graph).

“Indeed, the latest pesticides usage survey figures show about 30 per cent of the oilseed rape crop did not receive a neonicotinoid in 2010.”

In the context of the entire quote, I beleive he is stating that the neonicitoid seed treatment is targeted at flea beatles. I do not beleive he is stating that the seed treatment had no benefit, just that the benefit was with flea beatles and not necessarily aphids, which were a vector for a virus.

http://www.farmersguardian.com/arable-farming/agronomy/osr-varieties-and-establishment-looking-beyond-neonicotinoids/64840.article

LikeLike

Prophylactic seed treatments are not targeted, sprays are targeted. Most of the early papers on imidacloprid efficacy focus on aphids.

For a systemic pesticide it is a significant challenge to determine if a yield benefit arises as a result of the control of flea beetles, aphids or something else, however, as there has not been a yield benefit (UK OSR yields have flat-lined) this problem does not arise.

In addition to the 19 studies reviewed by the Heavy Costs report Goulson, D. (2013) (An overview of the environmental risks posed by neonicotinoid insecticides. Journal of Applied Ecology 50, 977-987) – also concludes that there is no clear yield benefit.

I have just gone through Bayer’s own literature dating back to 1992 and the evidence presented there of efficacy is also highly flaky – and that was their own un-peer reviewed studies – may blog on this myself at some point.

LikeLike

Is there evidence that neonics are effective crop protection products?

See here for an analysis of claims that they are- http://www.buglife.org.uk/blog/matt-shardlow-ceo/drugs-neonicotinoids-don%E2%80%99t-work-2

LikeLike

Additional to the fungicide synergy issue is this paper:-

Iwasa 2004 Mechanism for the differential toxicity of neonicotinoid insecticides in the honey bee, Apis mellifera

“Piperonyl butoxide,triflumizole and propiconazole increased honey bee toxicity of acetamiprid 6.0-, 244- and 105-fold and thiacloprid 154-, 1,141- and 559-fold”

LikeLike

Oilseed rape (canola) growers in France now have a new tool to replace neonics when they plant this fall. Methiocarb. Good news is it can control many of their key pests. Bad news is it’s highly toxic to bees and can also harm humans and non-insect wildlife. It’s effective for a shorter period of time than neonics and follow up sprays may be needed.

See http://www.fwi.co.uk/articles/16/06/2014/145082/treated-oilseed-rape-seed-on-offer-this-autumn.htm

And http://www.epa.gov/oppsrrd1/REDs/factsheets/0577fact.pdf

This is a prime example of why precautionary approaches don’t work. A real risk assessment would look at likely outcomes of a ban and understand this is a less desirable outcome.

The other option is to keep the bans coming until farmers have no options and yields fall, necessitating more area for cultivation and less for wildlife. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1365-2664.12035/abstract

LikeLike

Thanks Bill very interesting info.

I know that the pesticide companies have been claiming that the EU partial ban on Neonicotinoids was the result of the application of the precautionary principle. This is not true, you will find no reference to the precautionary principle in any of the relevant EC decision documents, risk assessments, regulations or press releases. This is because the decision to ban was taken by the EC after the European Food Safety Authority undertook an evidence based risk assessment (http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/press/news/130116.htm) that confirmed that the products and uses were a high risk to honeybees. Once a high risk to the environment or human health is confirmed the EU legislation gives little wriggle room to the EC, residual risk has to be managed through regulation.

The problem with a risk based approach, such as this, is that not all risks are apparent from the outset. Hence new pesticides can have a honeymoon period before the damage is detected and addressed. A risk assessment based approach results in a regime in which damaging pesticides are used for 10-15 years before the process rejects them and replaced by a less well understood chemical.

Your idealised model of risk assessment feels unfeasible, not only are risks unknown, the reaction of the market is unpredictable (as this development demonstrates!).

Just to re-emphasise, neonicotinoid seed treatments have not resulted in any reduction in follow up spraying, pyrethroid sales and applications have stayed constant. Seed treatment is an additional pesticide application.

Methiocarb as a seed treatment to replace neonics does sound like bad news, we will need to have a look at the toxicity evidence.

What is interesting is that the article you link to is from a British magazine. The suggestion appears to be that the company is making these French treated seeds available for use in the UK. However, currently methiocarb is not authorised as a Oilseed rape seed treatment in the UK (https://secure.pesticides.gov.uk/pestreg/getfullproduct.asp?productid=2954&pageno=1&origin=prodsearch). It is authorised as a maize seed treatment, but is being withdrawn in July 2014 (https://secure.pesticides.gov.uk/pestreg/getfile.asp?documentid=19606). There is a loophole in the EU legislation where it can be possible to import pre-treated seeds if that use is licensed in the EU country of origin. I am unsure if this is an authorised use in France, it would be surprising as the French Government is usually ahead of the UK Government in regulating pesticides (Paris is pesticide free for instance).

Clearly if methiocarb is as bad or worse than neonics then it should be risk assessed and similarly banned. If there is a lack of evidence to confirm the risks you claim then the only way it would be banned would be if the precautionary principle was applied.

Getting pesticide regulation right will mean that pesticides that are high risk to people and wildlife, or that do not provide yield benefits, do not come onto the market. It is your assumption that not allowing such pesticides would mean that there would be no pesticides on the market and yields would drop.

See – http://www.buglife.org.uk/blog/matt-shardlow-ceo/drugs-neonicotinoids-don%E2%80%99t-work-2 – for a review of the evidence (or lack of it) that neonicotinoid use improves yields significantly. If methiocarb is a less effective than this then the article is simply reporting a marketing scam.

In terms of organic farming the yield question is pretty complicated http://serenoregis.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/nature11069.pdf

LikeLike

I am also not a big fan of the precautionary principle. You can always hypothesize all manner of which harm can come to the environment or people using mathematical models, but when push comes to shove the best proof is from the system you’re interested in itself. Obviously, there are some caveats…but I really don’t believe that banning stuff at the first sign of possible harm-or political pressure is particularly wise.

I really should have replied to Mr. Shardlow’s comments, but I’ve got a lot of stuff going on in meatspace and Shardlow’s comments were very lengthy.

I realize that native pollinators are just as important, if not more important, than honeybees…however, the two issues are very different because these animals are affected by different things in different ways. Honeybees, for example, benefit from huge lumbering apes that treat them for diseases and supplement their diets in times of scarcity. We also pay more attention to honeybees than we do unmanaged bees, so that definitely affects that conversation.

So I’m only going to reply to the honeybee stuff for now. However, I do think Mr. Shardlow is in an excellent position to write an article about this subject from the perspective of native bees…and I extend an invitation for a guest post.

So here goes:

“CCD – while hives in the EU may occasionally show full CCD symptoms, it does not happen frequently enough for us to consider there to be one specific problem with honeybees. Over here the perception is that hive health has declined and overwintering success is now much poorer than it once was. Hence the question ‘are neonics the cause of CCD’ is of limited interest outside N America.”

I’m not sure what you mean by this comment. Who’s perception are we talking about-the beekeepers, scientists, or general public?

Over here the general perception of the public is that neonics are largely if not solely the cause of CCD, and that CCD is close to causing the extinction of the honey bee which means that we’ll need crops pollinated by tiny robot bees built by Monsanto in the next 10 years or so.

The perception of beekeepers and scientists is very different. I’ve heard lots of talk of stress-related factors, landscape changes, parasites, diseases…the stuff I wrote about in Colony Collapse Disorder: An Introduction. I’ve even heard some beekeepers muse that many health issues are simply because there are a lot of new beekeepers who don’t know how to properly manage their colonies.

Part of the reason I wrote this article was to address that disconnect between the people putting pressure on politicians to enact anti-neonic policies, and the scientists who are actually studying honeybee issues. Without knowing who’s perceptions we’re talking about, I’m not sure how to address the comment.

“Complexity of causes – there are many severe problems for bees and other pollinators and associated declines, and while wildflower loss is a key factor, insecticides doubtlessly also play a role. The European Food Standards Authority (EFSA) has determined three neonics to be a confirmed high risk for Honeybees.”

Well, yes…but risk is different than effect. We should be studying them because they’re persistent and taken up into plants. However, right now, there’s very little evidence of actual harm to honeybees.

Native bees, that could be a different story. If studies show actual harm, not potential for harm, but demonstrate that current practices hurt their populations in a way that causes significant decline of ecological function then it’s probably time to re-evaluate practices.

“Key question – the key question is whether the risk posed by pesticides to pollinator populations is ethically acceptable. Part of this question requires an ethical judgement and part is theoretically knowable – do the benefits to humans of using neonics out-weight the costs.”

Oh, I totally agree…and I’m agnostic on the issue. However, I don’t think that neonics are the entire reason for honeybee declines. You could make a case for small effects…but these wouldn’t be anywhere near the scale you hear from pop-sci sources.

“Lu – clearly this work is only relevant to the little Honeybee section of pollination services (and we don’t have lorry loads of professional Honeybees in the EU). The effects of the neonicotinoids on Honeybees in his two papers are interesting, but the dosing rates are indeed far higher than what would be encountered just through pollen and nectar in arable crops.”

I would actually disagree that his effects are interesting. Honeybees abandon their hives when treated with chemicals that effect their well-being. Hive abandonment needs to be studied more in bees, but the idea that insecticides would cause hive abandonment isn’t exactly a groundbreaking idea. Even if you wanted to claim this was his take-home message, he didn’t exactly do a great job of demonstrating that.

The fact that the symptoms of this abandonment don’t match CCD invalidates most if not all of his interpretation.

“There are however other forms of contact – dust, guttation fluid (Girolami et al. 2009 Translocation of Neonicotinoid Insecticides From Coated Seeds to Seedling Guttation Drops. A Novel Way of Intoxication for Bees) and puddles.”

Other technical changes in the composition of seed coatings and handling protocols of treated seeds have reduced neonic exposures to bees, which I think demonstrates my idea that risks to bees can be reduced by tools other than an outright ban.

Helen Thompson also raises some questions about guttation drops. It’s unknown whether they’re attractive to bees, or whether they’d be out at the same time as bees. So I think this needs to be looked into…but I’m not necessarily convinced it’s evidence that a ban is needed.

Click to access 2010Thompson.pdf

“In addition the potency of neonicotinoids can be higher in products (1000 times in Mesnage et al 2014 Major pesticides are more toxic to human cells than their declared active principles)”

Well, there’s also surfactants in the mix that could be more toxic to isolated cells than they’d be to the entire organism. In cell culture, they’re free to punch holes in cells that wouldn’t normally interact with the outside environment. It’s just not representative of what goes on in the system of interest. Thus, I don’t consider cell studies the least bit persuasive in this matter.

“when acting in synergy with fungicides (2 to 5 times in Biddinger et al 2013 Comparative Toxicities and Synergism of Apple Orchard Pesticides to Apis mellifera and Osmia cornifrons (Radowszkowski)).”

I’ve mentioned synergy before in passing, but haven’t really gotten into the subject in detail. There’s more pesticides which get into bee colonies at higher levels than neonics and I wouldn’t be surprised if, for example, some of the pyrethroid synergists caused the miticides to become more toxic.

Synergists are, from what I’ve read, a general pesticide issue as opposed to a specific neonic issue.

“Lu’s own theory that the neonics were concentrated into sugar syrup from treated maize crops that was then fed to bees does not appear to be evidenced and indeed sounds unlikely, but it would be interesting to hear from anyone who understands that purification process and could say if the theory is or is not feasible. The EU coverage of Lu’s work has generally been rather cautious http://www.independent.co.uk/environment/nature/new-pesticide-link-to-sudden-decline-in-bee-population-7622263.html”

According to USDA Pesticide Data Program, when imidacloprid is found in food, the maximum levels found are about 11 ppb. It’s not found in most food, and corn wasn’t tested.

So I guess it’s possible that the process could concentrate it, but Lu has never actually demonstrated that beekeepers are feeding their bees with corn syrup that’s contaminated with 100 ppb of imidacloprid. If that were true, I’m guessing it would have been detected much sooner, and CCD wouldn’t be so much of a mystery this time around.

Also, not to be nitpicky, but that article is indistinguishable from any US-authored popsci piece on Lu’s work. The article from Tom Philpott on Grist, for example, is really no different from this article.

“Do neonicotinoids work – we know that pollination services are worth billions, but what are the benefits of neonicotinoids. The US report ‘Heavy Costs’ shows that the evidence from field studies is not conclusive – it is not clear that the value of yield increases is higher than the costs of the insecticides – some of the UK costings indicate that our agriculture may be more profitable without neonics – more on this here – http://www.buglife.org.uk/blog/matt-shardlow-ceo/drugs-neonicotinoids-don%E2%80%99t-work.”

Yeah, that’s a separate issue…but again, it’s about how they’re used. They attack targets that other pesticides don’t attack, which makes them useful in some systems. If they’re not useful in seed treatments, they should probably be phased out.

“Field studies not finding an effect from neonicotinoids – there are several published studies that failed to find an effect in the field, and the best of these do offer reassurance that the impacts of neonicotinoids on honeybees are not instantly disastrous. As you say they do all have some limitations. But for some of them the problems run well beyond limitations. For instance Cutler & Scott-Dupree 2007 is based on a regulatory study that was invalidated by the Canadian authorities. It was considered meaningless because of 1) the small area of treated crop available to the ‘treatment’ hives, 2) the treated crop was also within the foraging range of the ‘control’ hives and 3) the ‘treatment’ and ‘control’ hives were pretty equally contaminated with neonics. You say you name ‘a few’ of the published field studies, but your list is pretty comprehensive!”

My point in mentioning them above was to point out that Lu should have addressed them, and not ignored them. There was obvious publication bias to the point where a funnel plot wasn’t needed to demonstrate this. I also believe he misrepresented the USDA paper he cited by not mentioning what it said about the risks of pyrethroids compared to neonics.

“Interaction – Field studies are hard work and therefore are not readily capable of determining ecosystem wide impacts such as interactions between pesticides or between pesticides and diseases – effects that have been proven in the laboratory – e.g. Doublet et al 2014 Bees under stress. sublethal doses of a neonicotinoid pesticide and pathogens interact to elevate honey bee mortality across the life cycle.”

Okay…so how do neonics compare to other pesticides in this regard? What’s the difference in effect sizes between neonics, organophosphates, pyrethroids and other classes of pesticides?

Again, by focusing on neonics you’re ignoring some of the larger issues with pesticides.

“Soil – neonics are surprisingly persistent in arable soils and are water soluble – this background build up may result in higher concentrations in pollen, nectar and water sources inside and outside arable fields. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ps.3836/abstract”

Well, yes they might do that. The numbers given in that paper are in the parts per billion range…which is high, but the question is how much of this gets back into the plant? That question as far as I know (which isn’t that far…I know more about the bug side of things) hasn’t been answered.

“You conclude that we should not tackle just one issue or one insecticide group and that is absolutely correct. But neonicotinoids are a significant concern and should be tackled.”

I think they should undergo scrutiny, but that’s really far away from an outright ban.

“And I do question your claim that “neonicotinoids frequently replace pesticides” we have generally found that seed treatments are additional. Pyrethroid use has not dropped since the introduction of neonicotinoids. Farmers are taking a belt and braces approach.”

See Bill’s comment above.

“Deryn Gilbey seeds and traits manager at Dekalb a majour supplier of Oil seed rape seed said in the Farmers Guardian this week that “the level of yield benefit from neonicotinoids in controlling its aphid vectors is highly questionable. Perhaps this is why there is no sign of any dramatic UK performance increase which could be linked to the introduction of neonicotinoids in the recent official yield record”.”

I’m not that familiar with the literature on sucking pests, but my questions about neonicotinoid efficacy focus on seed corn maggots (Delia platura), seed corn beetles (Stenolophus & Clivinia sp), and cutworms (Spodoptera sp.). However, and this is an important caveat to this concern, I do genetics and not pest management. I know these pests can be severe, but I’d also be surprised if they were more than a major annoyance to farmers. They’re not exactly key pests…but I’d imagine neonics would be effective against them.

LikeLike

Precautionary principle should be used when the scientific dots are in place, the theories are reasonable and the proof is lacking, it should not be just modelling and should have a reasonably robust basis in evidence.

CCD – perception of beekeepers, researchers, conservationists and decision makers is that this is not a significant EU problem, public and media a bit more varied as some do pick up the US concerns.

“very little evidence of actual harm to honeybees” – do you actually mean this? There really is a lot of evidence of field realistic levels of neonics harming honeybees:-

Alaux, C., Brunet, J. L., Dussaubat, C., Mondet, F., Tchamitchan, S., Cousin, M., Brillard, J., Baldy, A., Belzunces, L.P. & Le Conte, Y. (2010). Interactions between Nosema microspores and a neonicotinoid weaken honeybees (Apis mellifera). Environmental microbiology, 12(3), 774-782.

Aliouane, Y., el Hassani, A. K., Gary, V., Armengaud, C., Lambin, M., & Gauthier, M. (2009). Subchronic exposure of honeybees to sublethal doses of pesticides: effects on behavior. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 28(1), 113-122.

Almeida Rossi, C., Roat, T. C., Tavares, D. A., Cintra‐Socolowski, P., & Malaspina, O. (2013). Effects of sublethal doses of imidacloprid in malpighian tubules of africanized Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera, Apidae). Microscopy research and technique.

Arena, M., & Sgolastra, F. (2014). A meta-analysis comparing the sensitivity of bees to pesticides. Ecotoxicology, 1-11.

Aufauvre, J., Biron, D. G., Vidau, C., Fontbonne, R., Roudel, M., Diogon, M., Vigue, B., Belzunces, L.P., Delbac, F. & Blot, N. (2012). Parasite-insecticide interactions: a case study of Nosema ceranae and fipronil synergy on honeybee. Nature: Scientific reports, 2.

Biddinger, D. J., Robertson, J. L., Mullin, C., Frazier, J., Ashcraft, S. A., Rajotte, E. G., Joshi, N.K. & Vaughn, M. (2013). Comparative toxicities and synergism of apple orchard pesticides to Apis mellifera (L.) and Osmia cornifrons (Radoszkowski). PloS one, 8(9), e72587.

Boily, M., Sarrasin, B., DeBlois, C., Aras, P., & Chagnon, M. (2013). Acetylcholinesterase in honey bees (Apis mellifera) exposed to neonicotinoids, atrazine and glyphosate: laboratory and field experiments. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 1-12.

Colin, M. E., Bonmatin, J. M., Moineau, I., Gaimon, C., Brun, S., & Vermandere, J. P. (2004). A method to quantify and analyze the foraging activity of honey bees: relevance to the sublethal effects induced by systemic insecticides. Archives of environmental contamination and toxicology, 47(3), 387-395.

Cresswell, J. E., Page, C. J., Uygun, M. B., Holmbergh, M., Li, Y., Wheeler, J. G., Laycock, I., Pook, C.J., Hempel di Ibarra, N., Smirnoff, N. & Tyler, C. R. (2012). Differential sensitivity of honey bees and bumble bees to a dietary insecticide (imidacloprid). Zoology. 115, 365-371

Cutler, G. C., Scott‐Dupree, C. D., & Drexler, D. M. (2013). Honey bees, neonicotinoids and bee incident reports: the Canadian situation. Pest management science.

de Almeida Rossi, C., Roat, T. C., Tavares, D. A., Cintra-Socolowski, P., & Malaspina, O. (2013). Brain Morphophysiology of Africanized Bee Apis mellifera Exposed to Sublethal Doses of Imidacloprid. Archives of environmental contamination and toxicology, 1-10.

Decourtye, A., Armengaud, C., Renou, M., Devillers, J., Cluzeau, S., Gauthier, M., & Pham-Delègue, M. H. (2004). Imidacloprid impairs memory and brain metabolism in the honeybee (Apis mellifera L.). Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology, 78(2), 83-92.

Decourtye, A., Devillers, J., Aupinel, P., Brun, F., Bagnis, C., Fourrier, J., & Gauthier, M. (2011). Honeybee tracking with microchips: a new methodology to measure the effects of pesticides. Ecotoxicology, 20(2), 429-437.

Decourtye, A., Devillers, J., Cluzeau, S., Charreton, M., & Pham-Delègue, M. H. (2004). Effects of imidacloprid and deltamethrin on associative learning in honeybees under semi-field and laboratory conditions. Ecotoxicology and environmental safety, 57(3), 410-419.

Decourtye, A., Lacassie, E., & Pham‐Delègue, M. H. (2003). Learning performances of honeybees (Apis mellifera L) are differentially affected by imidacloprid according to the season. Pest management science, 59(3), 269-278.

Derecka, K., Blythe, M. J., Malla, S., Genereux, D. P., Guffanti, A., Pavan, P., Moles, A., Snart, C., Ryder, T., Ortori, C.A., Barrett, D.A., Schuster, E. & Stöger, R. (2013). Transient Exposure to Low Levels of Insecticide Affects Metabolic Networks of Honeybee Larvae. PloS one, 8(7), e68191.

Di Prisco, G., Cavaliere, V., Annoscia, D., Varricchio, P., Caprio, E., Nazzi, F., Gargiulo, G. & Pennacchio, F. (2013). Neonicotinoid clothianidin adversely affects insect immunity and promotes replication of a viral pathogen in honey bees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(46), 18466-18471.

Doublet, V., Labarussias, M., Miranda, J. R., Moritz, R. F., & Paxton, R. J. (2014). Bees under stress: sublethal doses of a neonicotinoid pesticide and pathogens interact to elevate honey bee mortality across the life cycle. Environmental Microbiology.

Eiri, D. M., & Nieh, J. C. (2012). A nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist affects honey bee sucrose responsiveness and decreases waggle dancing. The Journal of Experimental Biology, 215(12), 2022-2029.

Farooqui, T. (2013). A potential link among biogenic amines-based pesticides, learning and memory, and colony collapse disorder: a unique hypothesis. Neurochemistry international, 62(1), 122-136.

Faucon, J. P., Aurières, C., Drajnudel, P., Mathieu, L., Ribiere, M., Martel, A. C., Zeggane, S., Chauzat, M.P. & Aubert, M. F. (2005). Experimental study on the toxicity of imidacloprid given in syrup to honey bee (Apis mellifera) colonies. Pest management science, 61(2), 111-125.

Girolami, V., Marzaro, M., Vivan, L., Mazzon, L., Giorio, C., Marton, D., & Tapparo, A. (2013). Aerial powdering of bees inside mobile cages and the extent of neonicotinoid cloud surrounding corn drillers. Journal of Applied Entomology, 137(1-2), 35-44.

Girolami, V., Marzaro, M., Vivan, L., Mazzon, L., Greatti, M., Giorio, C., Marton, D. & Tapparo, A. (2012). Fatal powdering of bees in flight with particulates of neonicotinoids seed coating and humidity implication. Journal of applied entomology, 136(1‐2), 17-26.

Halm, M. P., Rortais, A., Arnold, G., Tasei, J. N., & Rault, S. (2006). New risk assessment approach for systemic insecticides: the case of honey bees and imidacloprid (Gaucho). Environmental Science & Technology, 40(7), 2448-2454.

Hatjina, .F. & Dogaroglu, T. (2010 ). Imidacloprid effect on honey bees under laboratory conditions using hoarding cages. In: Proceedings of the COLOSS Work Shop: Standardized methods for honey bee rearing in hoarding cages. Bologna, Italy

Hatjina, F., Papaefthimiou, C., Charistos, L., Dogaroglu, T., Bouga, M., Emmanouil, C., & Arnold, G. (2013). Sublethal doses of imidacloprid decreased size of hypopharyngeal glands and respiratory rhythm of honeybees in vivo. Apidologie, 44(4), 467-480.

Henry, M., Beguin, M., Requier, F., Rollin, O., Odoux, J. F., Aupinel, P., Aptel, J., Tchamitchian, S. & Decourtye, A. (2012). A common pesticide decreases foraging success and survival in honey bees. Science, 336(6079), 348-350.

Henry, M., Beguin, M., Requier, F., Rollin, O., Odoux, J. F., Aupinel, P., Aptel, J., Tchamitchian, S. & Decourtye, A. (2012). Response to comment on “A common pesticide decreases foraging success and survival in honey bees”. Science, 337(6101), 1453-1454.

Iwasa, T., Motoyama, N., Ambrose, J. T., & Roe, R. M. (2004). Mechanism for the differential toxicity of neonicotinoid insecticides in the honey bee, Apis mellifera. Crop Protection, 23(5), 371-378.

Krupke, C. H., Hunt, G. J., Eitzer, B. D., Andino, G., & Given, K. (2012). Multiple routes of pesticide exposure for honey bees living near agricultural fields. PLoS One, 7(1), e29268.

Lambin, M., Armengaud, C., Raymond, S., & Gauthier, M. (2001). Imidacloprid‐induced facilitation of the proboscis extension reflex habituation in the honeybee. Archives of Insect Biochemistry and Physiology, 48(3), 129-134.

Marzaro, M., Vivan, L., Targa, A., Mazzon, L., Mori, N., Greatti, M., Petrucco Toffolo, E., Di Bernardo, A., Giorio, C., Marton, D., Tapparo, A. & Girolami, V. (2011). Lethal aerial powdering of honey bees with neonicotinoids from fragments of maize seed coat. Bulletin of Insectology, 64(1), 119-126.

Matsumoto, T. (2013). Reduction in homing flights in the honey bee Apis mellifera after a sublethal dose of neonicotinoid insecticides. Bulletin of Insectology, 66(1), 1-9.

Matsumoto, T. (2013). Short-and long-term effects of neonicotinoid application in rice fields, on the mortality and colony collapse of honeybees (Apis mellifera). Journal of Apicultural Science, 57(2), 21-35.

Maxim, L., & Van der Sluijs, J. P. (2010). Expert explanations of honeybee losses in areas of extensive agriculture in France: Gaucho® compared with other supposed causal factors. Environmental Research Letters, 5(1), 014006.

Palmer, M. J., Moffat, C., Saranzewa, N., Harvey, J., Wright, G. A., & Connolly, C. N. (2013). Cholinergic pesticides cause mushroom body neuronal inactivation in honeybees. Nature communications, 4, 1634.

Pettis, J. S., Johnson, J., & Dively, G. (2012). Pesticide exposure in honey bees results in increased levels of the gut pathogen Nosema. Naturwissenschaften, 99(2), 153-158.

Rortais, A., Arnold, G., Halm, M. P., & Touffet-Briens, F. (2005). Modes of honeybees exposure to systemic insecticides: estimated amounts of contaminated pollen and nectar consumed by different categories of bees. Apidologie, 36(1), 71-83.

Schneider, C. W., Tautz, J., Grünewald, B., & Fuchs, S. (2012). RFID tracking of sublethal effects of two neonicotinoid insecticides on the foraging behavior of Apis mellifera. PLoS One, 7(1), e30023.

Tapparo, A., Marton, D., Giorio, C., Zanella, A., Soldà, L., Marzaro, M., … & Girolami, V. (2012). Assessment of the environmental exposure of honeybees to particulate matter containing neonicotinoid insecticides coming from corn coated seeds. Environmental science & technology, 46(5), 2592-2599.

Vidau, C., Diogon, M., Aufauvre, J., Fontbonne, R., Viguès, B., Brunet, J. L., … & Delbac, F. (2011). Exposure to sublethal doses of fipronil and thiacloprid highly increases mortality of honeybees previously infected by Nosema ceranae. PLoS One, 6(6), e21550.

Wu, J. Y., Anelli, C. M., & Sheppard, W. S. (2011). Sub-lethal effects of pesticide residues in brood comb on worker honey bee (Apis mellifera) development and longevity. PLoS One, 6(2), e14720.

Johnson, J. D. (2012). The role of pesticides on honey bee health and hive maintenance with an emphasis on the neonicotinoid, imidacloprid.

Guttation risk – read Frommberger, M.et al., 2012; Pistorius, J. et al., 2012; Reetz

et al. 2011; Schneider et al.,2012 and Joachimsmeier et al., 2012

“I don’t think that neonics are the neonics are the entire reason for honeybee declines” – of course there are other causative factors and it is indeed frustrating when the media only pick out the words ‘neonicotinoid’ and ‘honeybee’ and ignore the other risks and species, we all need to keep emphasising the need for a range of action to save a range of pollinators.

“technical changes in the composition of seed coatings and handling protocols of treated seeds have reduced neonic exposures to bees” – possibly – the results of efforts to reduce dust emission appear to have variable effects in the scientific papers (including continued fatal effects on bees), some reduction does not necessarily mean safe levels have been achieved, and there are also concerns that the technology is simply not being used – see Nuyttens et al 2013 Pesticide-laden dust emission and drift from treated seeds during seed drilling: a review.

“I would actually disagree that his effects are interesting.” You may be putting too much emphasis on the word ‘interesting’ it has a range of meaning in British – see http://www.buzzfeed.com/lukelewis/what-british-people-say-versus-what-they-mean.

Cost effectiveness “Yeah, that’s a separate issue” – it is not really a separate issue if a pesticide is not creating a yield benefit why would anyone defend its use? Why if they are not working do they need to be replaced? It’s about sprays as well as seed treatments as the link above makes clear.

“by focusing on neonics you’re ignoring some of the larger issues with pesticides.” By focusing on neonics we are establishing the principle that destroying populations of pollinators with chemicals is not morally acceptable and we are encouraging others to ask similar pertinent questions about other insecticides. It is all good and we fully support Barack Obama ordering “The Environmental Protection Agency shall assess the effect of pesticides, including neonicotinoids, on bee and other pollinator health and take action, as appropriate, to protect pollinators” – we hope that this review is meaningful and thorough and encourage all American scientists to participate – this is your chance to gather and submit evidence relating to the toxicology to pollinators of all pesticides – http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/06/20/presidential-memorandum-creating-federal-strategy-promote-health-honey-b

LikeLike

Matt,

I’m glad you are joining in on the discussion, but I want to point out to you that copying and pasting large sections of text is against our comment policy (see under the Biofortified Blog tab above). The reference list you pasted obviously came from somewhere else given its alphabetical order and formatting. In the future, please link to the list elsewhere (you can put it in a forum post and link to that if you don’t have a web link) so that readers aren’t presented with a wall-of-text that will interfere with discussion. Thanks.

LikeLike

OK point taken. A filtered download from our database so not available anywhere else.

LikeLike

Biddinger also has this to say on neonics:

LikeLike

This comment is a reply to a conversation between Save_Bees and Larissa Walker I had over Twitter concerning where activists are putting their energies. I would also welcome Mr. Shardlow’s comments on the matter.

The links below are google news searches for Organophosphates, Pyrethroids and Neonicotinoids. In the context of bee safety, OPs and PYRs are found in significant amounts in beehives far more frequently than neonicotinoids, but neonics have about 4x more media coverage.

Neonics: 590 google news results, mostly about bees.

https://www.google.com/?gws_rd=ssl#q=neonicotinoids&safe=off&tbm=nws

Pyrethroids: 64 google news results, most not about bees.

https://www.google.com/?gws_rd=ssl#q=pyrethroids&safe=off&tbm=nws

Organophosphates: 84 google news results, most not about bees

https://www.google.com/?gws_rd=ssl#q=organophosphates&safe=off&tbm=nws

I can see good reasons behind some of the campaigns. A lot of people want to plant pollinator friendly gardens, and given the high detections of neonics in ornamental plants I think labeling, limiting or eliminating neonic use in ornamental crops might not be a bad idea…especially for plants used for projects involving pollinators.

So I’m not criticizing campaigns like that, per se, but I do have questions about whether eliminating this particular practice would increase the use of other pesticides for these uses. Neonics aren’t that bad for people, especially compared to some other groups of pesticides…and I’d be concerned that spraying around populated areas might be increased as a result. So I think this needs to be considered, and I haven’t seen any concern for this possibility raised by activist groups.

The one response raised by Walker was that neonics are ‘a problem that can be taken care of right now’, and I’m not sure that that’s a wise approach given the data discussed above. There are some questions raised by these campaigns that I’d like to see answered.

1.) Why focus on a group of pesticides that’s found in low levels in a minority of bee colonies? Why not focus on groups of chemicals that are found in high levels in a wider proportion of colonies?

2.) Why not focus on pressuring legislators to restrict pesticide use around flowering crops which are attractive to bees?

It would seem that either of these two approaches would yield results that would have more beneficial effects on bees, and I don’t understand the emphasis on neonics when other pesticides seem to be a bigger large-scale problem.

LikeLike

Answered most of this above, action on neonics does not prevent action on any other damaging pesticide.

1) Risk = exposure+toxicity – good evidence base for neonics, better evidence needed for other insecticides.

2) We are, but complicated by soil persistence which causes pollinator exposure in untreated crops.

LikeLike

Matt,

The methiocarb toxicity data are available through the EPA’s RED. It’s listed as class I.

I think what your group is doing for native pollinators is a great model. I don’t mean to come off as dismissive of those goals. In terms of neonic use for ag applications, however, the data support a conclusion that the risks for long term honey bee health are low.

Continued bans of ag chemicals force us into a land sharing model where productivity is diminished and land for wildlife that doesn’t get along well with people or managed environments is limited. Land sparing is a better choice if we’re going to supply global import demands. The EU depends on soybean shipments from South America as does China. If Brazil pursued a land sharing model, they’d have to clear the Amazon basin and the Cerrado to meet demands from Europe and Asia. What would Japan, Mexico and Korea do without corn from the US?

I agree with Joe that you should put a post together for Biofortified. No one benefits from hearing only one side of the evidence.

I understand the Task Force on Systemic Pesticides will release a report on Tuesday examining the impacts of neonics on bees and other animals. Any thoughts you have on that would be interesting to read.

LikeLike

“the data support a conclusion that the risks for long term honey bee health are low” this was not the conclusion of the biggest risk assessment work done to date:-

http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/press/news/130116.htm

With specific regard to neonics the evidence reviews do not indicate a significant yield benefit so it is far from certain that removing them would mean that more land was needed for agriculture (see ‘Heavy Costs’ and Goulson 2013).

First part of the Task Force on Systemic Pesticides report is now published – http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11356-014-3180-5

This is the review of the effects of neonics on vertebrates it says, amongst other things, that “Use of imidacloprid and clothianidin as seed treatments on some crops poses risks to small birds” and concludes that:

“Evidence presented here suggests that the systemic insecticides, neonicotinoids and fipronil, are capable of exerting direct and indirect effects on terrestrial and aquatic vertebrate wildlife, thus warranting further review of their environmental safety.”

More tomorrow…..

LikeLike

Systemic pesticides pose global threat to biodiversity and ecosystem services

The conclusions of a new meta-analysis of the systemic pesticides neonicotinoids and fipronil (neonics) confirm that they are causing significant damage to a wide range of beneficial invertebrate species and are a key factor in the decline of bees.

http://www.iucn.org/news_homepage/news_by_date/?16025/Systemic-Pesticides-Pose-Global-Threat-to-Biodiversity-And-Ecosystem-Services

First paper is out, more to follow.

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11356-014-3180-5

LikeLike

I’m going to apologize for not responding in order, because I kind of want to split up different topics. I originally wrote the article to point out the difference between the media and scientific communities, and I want to keep these organized.

I’m also going to reply in parts, so my replies might take a few days. I’ll specify which I’ll reply to later in my responses.

But, in general, this has been a great discussion and I think it’s beneficial to continue!

[quote=Matt]Precautionary principle should be used when the scientific dots are in place, the theories are reasonable and the proof is lacking, it should not be just modelling and should have a reasonably robust basis in evidence.[/quote]

So, then is the question what we mean by reasonably robust?

Because a lot of studies that have been done are lab-based studies. These are useful in indicating potential problems, because it gives us a way to eliminate hypothesis without resorting to studies which are difficult, and complicated, and expensive. However, laboratory studies don’t provide any sort of proof-positive concerns. Field and landscape studies are needed to demonstrate that lab effects hold up, at least in my (perhaps inconsequential) opinion.

[quote=Matt]CCD – perception of beekeepers, researchers, conservationists and decision makers is that this is not a significant EU problem, public and media a bit more varied as some do pick up the US concerns.[/quote]

I’ve always wondered if this was due to actual occurrence, or if it was just low detections. Would you be willing to shed more light on this from a European perspective?

[quote= Matt]“very little evidence of actual harm to honeybees” – do you actually mean this? There really is a lot of evidence of field realistic levels of neonics harming honeybees:-snip[/quote]

As Karl said, posting walls of articles is against the rules here. This is because large walls of unexplained text serves as a barrier to conversation. Some use this as a way to cut conversation off-it’s a rhetorical method known as the Gish Gallop. Others simply get overexcited, and post a bunch of reading material.

However I don’t think these articles are completely irrelevent, and I do think an in-depth discussion of some of these articles could really help put some things I did not address in the above post (or my previous post) into perspective. If you’re willing, I think an in-depth discussion of a few of these articles would be of great benefit to our readers.

I have mixed opinions on some of these articles, and of lab studies in general. Some lab studies do hint at potential problems which neonics can exacerbate. For example, Alaux et. al 2010 found that neonics exacerbated Nosema infection at 5ppb…which is within a realistic field dose range. This result has been backed up by the Pettis group, which did similar experiments independently. So I think these results are a great example of how neonics stress bees in significant ways at sublethal doses.