If you’re like me, grocery shopping is both a pleasure and a struggle. I love to see which fresh produce and fancy cheeses are available! But meal planning is a challenge when your household contains one adventurous vegetarian (that’s me!) and two choosy eaters. Our grocery budget can get a bit out of control as I’m trying to meet each person’s needs and wants. Still, things could be a lot worse. I could be buying foods with organic or non-GMO labels.

What do organic and non-GMO labels even mean?

Farmers and manufacturers can gain organic certification if they follow certain processes related to how they grow crops and process foods. Organic is commonly touted as pesticide-free, but organic farmers have a list of pesticides they may choose from. Conventional agriculture may use any registered pesticide, and may use any approved genetically engineered crops (commonly called genetically modified organisms or GMOs). Whether you choose organic or conventional, there is no need for concern about pesticide residues, particularly for products grown in the United States.

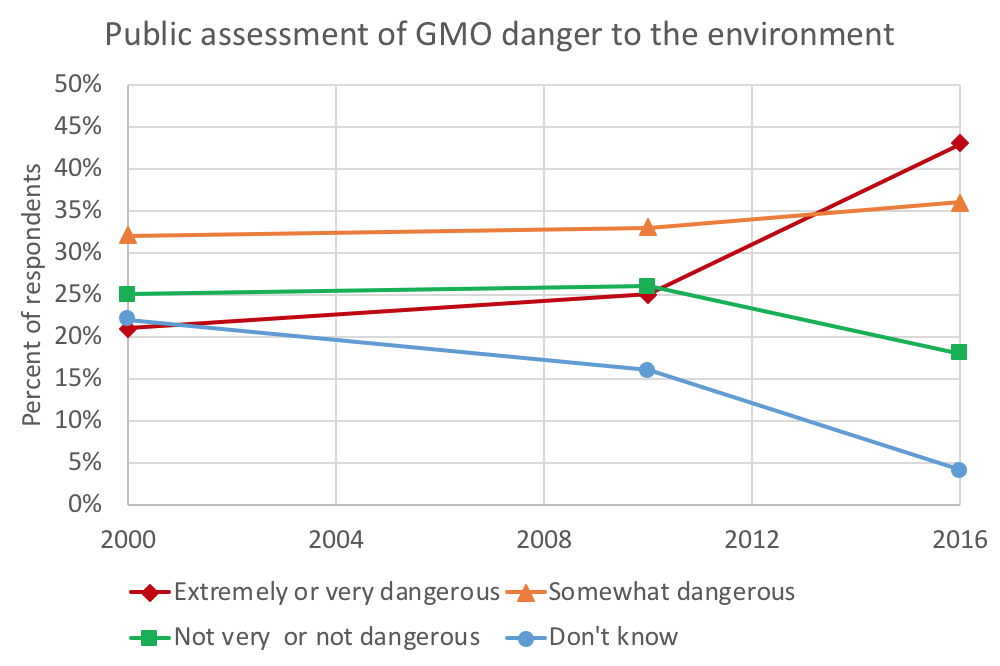

While academics and government agencies debate the definition of GMO, for many people the meaning is simple. GMO signifies all they want to avoid about modern agriculture. That’s an unfortunate point of view, because biotechnology is simply a breeding process that can be used in any farming system. Decades of research have found the process of genetic engineering to be safe, and consumer concerns about GMOs are largely unfounded.

What does the data say?

Many people assume that organic and non-GMO foods are more expensive, but is that really the case? In the recently published The price of non-genetically modified (non-GM) food, agricultural economists Nicholas Kalaitzandonakes, Jayson Lusk, and Alexandre Magnier used Nielsen product data to actually look at consumer purchasing and prices of organic and non-GMO foods from 2009 to 2016.

The researchers considered the average price premium for organic and non-GMO options in four food categories: salad and cooking oils, tortilla chips, breakfast cereal, and ice cream. Most products in the study were labeled either organic or non-GMO. Since GMOs are prohibited in organic agriculture, a non-GMO label on an organic product is redundant. However, a product can be non-GMO but not organic. Products with both labels were counted as organic for this study to avoid double-counting.

In Want non-GMO? How much more will it cost?, Jayson (one of the paper’s authors) writes: “We picked these product categories because they represent classes of products for which the potential impact of changes in the raw ingredients on the final retail price might be large (i.e., soybean or corn oil for which the supply is primarily GMO) to small (i.e., ice cream where the value share of GMO crops and their derivatives (e.g. corn syrup) is probably less than 5%).”

The high price of organic and non-GMO labels

The researchers found that sales of organic and non-GMO products vary considerably by category. Organic products made up nearly 10% of cooking and salad oils and nearly 8% of tortilla chips sold in 2016 – much higher than I’d expected.

The ice cream category was also very surprising. Given the specific marketing messages around organic dairy, I was expecting organic ice cream sales to be higher than non-GMO but the data shows the opposite. The Non-GMO Project verifies “non-GMO milk”, even though there are no genetically engineered cows. All milk is non-GMO by definition, although cows might be fed non-GMO or conventional feed.

Looking at data from 2009 to 2016, the researchers found that organic and non-GMO foods in all four categories had higher prices compared to conventional foods.

Organic ice cream was over 60% more expensive than conventional ice cream. Organic dairy is heavily marketed as superior to conventional dairy, even though there is no practical difference in the final product or in how the animals are treated. Apparently that marketing is nonetheless effective in commanding higher prices.

More Labels, more problems

In addition to the organic and non-GMO labels, the authors looked at a number of other labels.

- “Natural” labels increased prices in all four food categories, including increasing ice cream prices by over 36%. There is no definition for “natural” when it comes to food.

- “Gluten free” labels increased prices in all four food categories, including increasing breakfast cereal prices by almost 40%. Less than 1% of people in the US have celiac disease, but increasing numbers are avoiding gluten for claimed health benefits.

- “Multigrain” or “whole grain” labels increased prices of tortilla chips by 25%, and increased breakfast cereal prices by nearly 7%. While eating whole grains is important, chips are never a health food.

- “No hormones” labels on ice cream increased prices by 15%. All milk naturally contains the hormone estrogen, regardless of how the cows were raised.

- Some labels did not increase or decrease prices in the four food categories: “no preservative”, “rich in antioxidants”, “rich in vitamins”, “fat free”, “low fat”, “low salt/sodium”, and “low sugar/no sugar added”. Unlike most of the other labels, these labels actually indicate some potential health benefits of a product.

- “Low calorie” labels on ice cream decreased prices by 20%, probably because low calorie ice cream never tastes as good as high calorie ice cream!

Higher food prices due to these labels impact our budgets

The US Department of Agriculture regularly develops Thrifty, Low-Cost, Moderate-Cost, and Liberal Food Plans. Each plan represents a healthy diet for that price point, and includes grains, vegetables, fruits, dairy, meat, beans, and other foods. I like to check my grocery budget against the USDA plans, hoping to stay within the low to moderate range for my family of 3. The monthly budget for an average family of 4 with two children is $642.30 for thrifty, $844.90 for low-cost, $1052.40 for moderate-cost, and $1279.40 for liberal food plans.

Based on the data in this paper, avoiding unnecessary labels means a smaller grocery bill. I’d love to see a follow-up paper that looks at USDA food plan costs with conventional, organic, and non-GMO products. Even if a family doesn’t often splurge on ice cream, cooking oil and breakfast cereal are pretty standard in most households, and these results indicate that there are likely price increases across most if not all food categories. While some families find extreme couponing, shopping around, buying bulk, and other practices help to reduce their grocery bills – all of that takes time. And time is money, too.

Don’t fall for labels

While some labeling can be informative and improve transparency, labels can also lead to confusion. Labels can make perfectly healthy food seem suspect – do you want to buy regular bananas or organic bananas? The organic bananas costs 20 cents more a pound, so they must be better, right? But a higher price doesn’t necessarily signify a higher quality product. A higher price also doesn’t necessarily mean that product costs more to produce.

Food labels can also make us think unhealthy foods are healthy. Organic cookies are still cookies. Organic chips are still chips. Further, inaccurate claims about foods can cause people to make less healthy choices, such as buying less produce after hearing false claims about pesticide residues.

To make matters worse, there are many examples of products where a switch to organic or non-GMO resulted in smaller package sizes, fewer nutrients, and even overall worse nutrition (higher calories, more sugar) along with the higher price.

It’s no wonder why marketers slap on as many labels as possible – they want to charge you more! Consider what grocery stores are doing to hide price differences. Many stores now put all of the organic products in one section, making it harder for us compare prices. We’re also more likely to buy other organic items while in that section. So, don’t fall for the labels. As any registered dietitian will tell you, the food label that matters most is the Nutrition Facts label.

Note: This article was originally posted on the SciMoms blog, and has been republished here with permission.