I hope that you and those who you care about are safe during the COVID-19 pandemic. Without a doubt, this is a difficult time for so many people around the country and the world. I don’t need to tell you the number of people who have gotten sick or died because you hear it every day, and tomorrow it will just be higher. As doctors, nurses, scientists, public leaders, grocery store workers, farmers, and more work to slow the spread of the disease and mitigate its impacts, it can be difficult to find ways to help besides staying at home and protecting yourself and your family. Here’s what we’re doing to help, and how you can help too: Biofortified is making fabric masks for farm workers – and doing research on fabric mask efficacy too! We need your support so that this can continue until the pandemic is over. Read about our efforts, and see below how you can contribute to these projects.

Sewing our way to safety and sanity

As many of you know, I’m very good at sewing. I’m known for my homemade shirts! When I found my research at UC Riverside shut down mid-March, I knew that I could contribute by sewing masks so that people could keep each other safer when they have to go outside. A friend of mine, comedian Kristina Wong, tagged me and a few others she knew who could sew, so she had the same idea. She knew about my sewing because I helped her finish some costumes and props for some of her public performances, and she was getting a group together. Soon she was all over the news with her effort, and the Auntie Sewing Squad was born.

She’s been doing a great job organizing the now 600-strong group of volunteer cutters, seamsters, drivers and more, and we are churning out thousands of masks per week. Requests come in from all around the country, from New York hospitals to local care facilities and grocery stores, farms, and First Nations who have been hit harder by the virus than most. For instance, today there’s a van heading from the group to the Navajo Nation with masks, fabric, sewing machines, medical supplies, and more. In addition to sewing masks, I’ve been cutting and crimping nose wires to send to other members of the group. It has been gratifying to see people posting pictures of all our masks, and when I feel stressed about what is going on – spending an hour cutting fabric, sewing, or attaching elastic really helps keep me sane.

Right: Masks and nose wires right before I drop them off at the post office.

Masks can protect the food supply

Many people have lost their jobs or have been severely impacted by this pandemic. We worry about getting sick, or being able to get supplies like toilet paper and medicines, and especially – food. There are countless articles about supply problems, and food being dumped because restaurants aren’t buying as much. And there are outbreaks of the virus at grocery stores and food processing facilities. Meat packing plants have proven to be especially vulnerable, and even today a Maruchan ramen factory reported an outbreak, while farmers are worried about having enough labor to harvest their crops. Fabric masks for farm workers and other essential people can help keep them safe, and keep the rest of us stuck at home – fed.

Many food system jobs are not well-paid, and many people who have these jobs do not have access to masks that can help protect themselves and each other. They are getting sick. Providing masks for communities that are both under-served and critical will help slow the spread of the disease, help ensure stability in the food supply, and help states get on track toward gradually opening their economies. Yesterday, I was pleased to mail 100 of my masks to farm workers in Ventura, CA, and more requests to our sewing group keep coming in. Your donations can help get masks to farm workers and more.

Sew what? How about some science?

We don’t have enough N95 masks for everyone, let alone health care workers. Fabric masks aren’t a substitute for N95 masks, but they can lower your risk of contracting the disease and – especially – spreading it to others. While we know that fabric masks can help – we don’t exactly know by how much. There are multiple stories about research being done on mask materials, and also some about testing mask designs. Many of these involve ideal conditions, or make simple measurements that don’t give us the full range of data we need to make informed decisions about the impact of fabric masks. As a scientist who sews, and works at a University with excellent research programs in pollution and aerosols, setting up a research project on fabric masks is a natural fit.

I have already started working with the lab of Dr. Yang Wang at Missouri Science & Tech, whose graduate student Weixing Hao has been testing the filtration efficiency and pressure drop of fabrics and other materials, some of which I have sent them, along with Dr. Maya Trotz at the University of Southern Florida and Dr. Linsey Marr at Virginia Tech. This means that we can find out how well multiple layers of each material can filter particles from the air, as well as how breathable the materials are. Results keep coming in, and you can access them publicly here. But what it can’t tell us is how well these materials work in practice in masks worn by people.

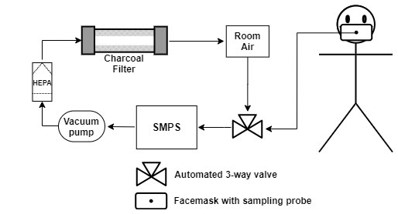

I really wanted to test the fabric masks themselves, and on real human beings. Dr. Wang helped me connect to scientists at UC Riverside who were experts in aerosols, and Dr. Don Collins and his graduate student Candice Sirmollo stepped up to help. My PI Dr. Mikeal Roose is very supportive. Together we got to work designing a project and are now busy getting the approvals we need to proceed. It’s looking very good (we got our IRB determination letter Friday), but there are a lot of steps left to take. I’m excited to get started, so I’ve already started buying the supplies we need to get ready, including special probes to be installed inside the masks to sample the air for testing. Once we get clearance to proceed, I want masks ready to be tried on for our first experiments. We want to get our results out to the public as soon as possible, so there’s no time to waste!

How you can support us

I count myself privileged to continue to work and be paid while many are having difficulty making ends meet. The mask sewing is voluntary, but it takes money to buy mask supplies, ship nose wires and completed masks, and to buy specialized equipment for our proposed research. Biofortified has spent funds out of our very tiny budget to meet these needs, and we could really use your support to help us in these efforts. Donations will go toward sewing and shipping masks, supporting other seamsters in the Auntie Sewing Squad, purchasing materials to test with Dr. Wang’s group, and purchasing supplies to be donated to the fabric mask fit-testing project when and if it receives final approval. The sampling probes alone were almost $300, which will enable us to test 500 masks.

If you are able to, please consider making a donation today.

If you wish to donate directly to the Auntie Sewing Squad and support everyone’s mask-making volunteer efforts, you can can send money one of two ways (tell her Karl sent you):

- Kristina Wong PayPal General Donations using (Friends & Family): k@kristinasherylwong.com

- Kristina Wong Venmo General Donations HERE: “GiveKristinaWongMoney”

When the mask fit testing research is fully approved, I will post how you can donate directly to the University to support our research.

If you find yourself in a position to be able to help, you have our thanks. Stay safe, and we’ll share our progress here as we move forward.

Find out more

- Can you sew? Or can you help in other ways in the Los Angeles or San Francisco areas? Join the Auntie Sewing Squad on Facebook here. Subscribe to the YouTube Channel. And Instagram.

- Read some helpful articles about COVID-19 written by the SciMoms.

- Visit Dr. Yang Wang’s research website. Follow him on Twitter.

- Follow Dr. Linsey Marr on Twitter.

- Follow Dr. Maya Trotz on Twitter.

Resources for farms (from the American Farm Bureau site):

- Agricultural Worker Protection Guidance – Maryland Farm Bureau

- Ag Worksite Checklist – University of California, Davis

- Workplace Guidelines and Posters – CDC

- Guidance for Farms and On-Farm Deliveries – Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture

- Protective Measures for U-Pick Farms – South Carolina Farm Bureau

- Coronavirus Prevention & Control for Farms – Cornell University

- How to Build a Field Handwashing Station – South Carolina Farm Bureau