Written by Caroline Coatney

The recent decision of General Mills to produce GMO-free Cheerios is interesting from marketing, political, and biological angles. However, what I am interested in most is if GMO Inside and other anti-GMO groups will realize that the process of producing the GMO ingredients in Cheerios (corn starch and sugar) is identical in principle to the way insulin—and many other drugs, like your dog’s rabies shot—is made. If they adamantly insist on GMO-free food products, how can they not extend their request to all pharmaceutical products made with the same genetic engineering technology? If we must have GMO-free Cheerios, then we must have GMO-free insulin, right?

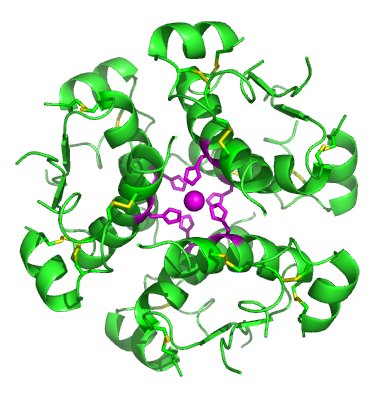

Insulin is made, in principle, the same way the GMO corn starch and GMO sugar in Cheerios is. To start, the DNA sequence for human insulin is inserted into the bacteria E. coli, which creates an organism that now has DNA from two very different species in it. This new E. coli is a genetically modified organism (GMO) and serves as a cheap factory for mass-producing the human insulin protein. After a while, the E. coli bacteria has produced large amounts of the human protein to the point where the protein can be extracted from the bacteria cells and purified before being packaged into insulin shots. The insulin protein produced via genetic engineering is chemically identical to the insulin protein made in a healthy human body.

Genetically engineered plants are made through a very similar process. A gene of particular interest is inserted into a plant. (For details on how exactly this happens, check out this video from GMO Answers.) This gene may be useful for insect resistance, like the Bt genes, or useful for other agricultural purposes. Eventually the plant is harvested and processed for its crop. The actual plant tissue that has the genetically engineered DNA in it may or may not be directly eaten by consumers; it depends on what the plant is harvested for. In the case of Cheerios, corn starch and sugar are processed and refined from their respective plants with DNA removed. The corn starch and sugar produced without GMOs is chemically identical to their GMO counterparts; the genes added to the GMO plants did not change the properties of corn starch or sugar.

The genetic engineering processes of making insulin, corn starch, and sugar are the same in principle. This “sameness” adds unavoidable complexity to the GMO discussion. Genetic engineering seems to have developed two faces: life-threatening and life-saving. Anti-GMO organizations will sooner or later have to confront this contradicting duality, especially as genetic engineering opens a new chapter for medical advances, such as the potential cures for cancer and HIV.

So when should we expect GMO Inside to set up another petition, this time for GMO-free insulin? Part of me hopes soon since maybe the juxtaposition of a long-trusted drug and anti-GMO propaganda will be enough to resolve the two faces of genetic engineering into one honest representation.

Written by Guest Expert

Caroline Coatney is a plant breeder with experience in science communication and science policy. She has a Masters degree in plant biology from the University of Georgia.

I have written a piece about GMO plant medicines that I hope will be useful when it gets published. Did you know there’s already a GMO plant that makes collagen for bandages and wound repair? It has so many benefits: not an animal or cadaver source that risk infectious agents, not in animal cells culture that has some risks for humans, large quantities, lower cost.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23941988

If people start going wild banning GMOs they are going to accidentally take down medical stuff that they will really regret losing.

But it still always surprises me how many people don’t know insulin is a GMO. It’s great to have this piece to link to now–thanks!

LikeLike

And don’t forget chymosin. Everyone likes cheese!

LikeLike

People need insulin. People don’t need genetically modified food ingredients. Medicines are put through rigorous clinical tests before they’re put on the market. The Food and Drug Administration does not perform or require ANY safety testing of new GMO food crops. They rely SOLELY on voluntary safety assessments performed by the corporations set to benefit from the sale of their new GMO seeds. Finally, don’t you think the possibilities for collateral damage from gene insertion are a minimal with a simple E.coli than with a eukaryotic plant?

LikeLike

The FDA does require safety testing of GMO foods. Despite the rule on the books that the safety consultation is voluntary, the FDA has broad powers to allow or ban any food, so when one company decided not to participate, the FDA made them “volunteer.” http://grist.org/food/the-gm-safety-dance-whats-rule-and-whats-real/

Also, the GMO-derived insulin only had to show that it was identical in properties to the non-GMO insulin which had already been approved and developed as a medicine. That’s why crop composition is scrutinized for every GMO plant.

LikeLike

You say: “The FDA does require safety testing of GMO foods. Despite the rule on the books that the safety consultation is voluntary, the FDA has broad powers to allow or ban any food, …”

While the GMO developers may perform safety testing in-house, the FDA does not require safety testing of GMO foods and its “broad powers” to ban any food are limited.

Even if the FDA wanted to throw its weight around, it “has to show that there may be a problem with the food, as opposed to the company needing to prove it’s safe to FDA’s satisfaction before it can get on the market,” according to Gregory Jaffe. (Jafee directs the Biotechnology Project at the Center for Science in the Public Interest, on whose report — “HOLES IN THE BIOTECH SAFETY NET: FDA Policy Does Not Assure the Safety of Genetically Engineered Foods” — you rely.) If the GMO developer won’t share their data, the FDA would have no evidence either way.

Moreover, the FDA has already ruled 20+ years ago that GE foods are substantially equivalent to conventionally produced foods and GE crops are generally recognized as safe — and so shouldn’t be held to any different standard than other foods.

The Grist article you cite relied heavily on representations made by Val Giddings. Giddings seems to employ one of the well-worn political “strategies … saying things whose opposite is true” (to borrow from Aaron Schwarz) repeatedly with bravado.

He assures us vaguely that the FDA cannot even envision a GMO developer not consulting with them. “These people are terrified of the FDA,” he says without proof. (What about imported food, with GMO ingredients from Shanghai Heavy Bio-Industries [hypothetically]?)

Months later, Giddings specifically distinguished between countries where food safety testing was “REQUIRED” and “MANDATORY” … and the United States. While on a panel (http://www.heritage.org/events/2013/10/food-labeling at 1:08:20), Giddings said the following in response to a question about how the letters the FDA sends out to every GMO developer after “voluntary consultations” do not present any findings or opinion from the FDA, but merely cite assurances from the developer:

“But because they [the FDA] have valued the input of their lawyers on this more than they have their scientists, that results in the verbiage that you cite, which is unfortunate, I think.

Having said that, every other major country in the world that has regulations on these food safety issues REQUIRES these sorts of reviews. And they reviews the exact same dossiers that FDA looks at. And they reach the same conclusions, that these products are safe. … And as I said, every single one of those foods has gone through these processes, whether it’s voluntary here or not, it’s MANDATORY elsewhere, and the views are identical in content…”

So Giddings might better direct his flames inward (quoting his Grist interview with my edits in square brackets): “In my opinion it is misleading to and past the point of dishonesty to claim that FDA does [] require safety testing,” and “A Jesuit would blush at the rhetorical convolutions to which the activist [pro]ponents resort to make it seem otherwise.”

So while the FDA normally relies almost exclusively on information provided by the biotech crop developer, it is unclear whether the FDA has the legal authority to stop any food when no evidence has been volunteered.

The bigger problem is, of course, the FDA’s lack of will to meaningfully squeeze developers and whether the chummy voluntary assurances mean anything.

Rather than trust in promises that the agency will be honorable and proactive, I think it is prudent to start with a more skeptical assumption that the folks in authority at the FDA are buddies with the executives of the biotech seed industry. Their common interests are abundantly evidenced by the “revolving door” between regulators and industry.

Without rules, regulations or statutes to govern the FDA, the agency becomes Michael Taylor. When the FDA faces a tough call, one should ask, “What would Michael Taylor do?” (Borrowing from the title of Ryan Lochte’s eponymous reality TV show.)

The following additional dereliction in food safety by the FDA suggests the answer: http://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/fda-allows-antibiotics-in-animal-feed-despite-potential-risk-to-human-health-report-claims/2014/01/27/63a73a88-869e-11e3-916e-e01534b1e132_story.html

.

You say: “when one company decided not to participate, the FDA made them ‘volunteer.’ http://grist.org/food/the-gm-safety-dance-whats-rule-and-whats-real/”

This assertion is not supported by your citation. According to the Grist story, the FDA did not make any of the 3 GMO companies who refused its request for more data actually comply.

LikeLike

After such a detailed discussion about what FDA can and can’t do and whether GMO testing regulations are strict or lax, can you now comment on a few specific examples? Like, was Starlink corn subjected to sufficient safety review before being banned from the food supply?

Also, can you tell us what amount of time typically elapses between the time a developer gives FDA an application and the time that FDA gives the developer its decision?

LikeLike

GMO’s won’t die because they are lethal. They won’t die because they are even slightly toxic or that they haven’t had proper testing. They’ll die because they don’t work. Farmers are dropping them because they cost 25% more to use. These farmers that started five years ago are now spraying huge amounts of herbicides to counter the weeds and bugs that are now resistant. Crop yeilds are significantly lower in GMO fields, and on top of all that, the public doesn’t want them. Every time you mess with nature, nature messes back. This is not a battle you can win. Find cures, nature will make variants that are more virulent. Make a BT type crop. Nature will make a resistant weed and bug. You have to work with nature. You step outside the bounds and you will get slapped. Stacking the FDA with Monsanto employees has been brought to light because of this mess. That will be dealt with , in time. It’s ending. We won this war,and we never even had to fire a shot.

LikeLike

Sounds good for your perspective. So essentially the solution to ending the reign of GMOs around the world is to sit back and watch what works and what doesn’t? If they do work, then we’ll know that as well and the technology will stick around. Finding out what happens without firing shots is always a plus.

LikeLike

“Crop yeilds[sic] are significantly lower in GMO fields…”

That is patently false. I have seen the increase in yields both from hybridization and genetic modification. I should clarify here, as hybridization is genetic modification. By the latter, I mean the purposeful addition of genetic code to achieve more rapidly and thoroughly the aim of the former.

And I won’t even get into “organic” vs. “non-organic.” I drive past bordering fields (separated by the road on which I travel) that clearly show the difference between the two. While I won’t say every proponent of “organic” is of this mindset, but I know there is a lot of support for better-to-do nations helping out the less fortunate. Here is where there is a clear example of not being able to do both. The yields of organic farms is horrible, and I can’t stress that enough. What it ultimately comes down to with the issue of both “organic” and “GMO” crops is that they are both crucial to sustaining the population that exists on this planet.

LikeLike

This certainly explains the 90%+ adoption rates.

Or, to cover it slightly more truthfully… in areas where resistance has arisen farmers have had to go back to what they were doing, while clamoring for the next trait that will make life easier again.

If by lower you mean essentially the same in the US and higher pretty much everywhere else then absolutely, yes.

Only, it has to be said, if you’re a pseudonymous blogger.

Truefax… polio in the West is so much damn stronger since we eradicated it with vaccination. One also works under the rather dim assumption that a fix now is the only fix intended for all time… sure, resistances can and do evolve, but to argue that this means we shouldn’t try to create ‘cures’ and manage resistance is simply silly.

Nature provided us with agrobacterium, Bacillus thuringeinsis, restriction enzymes, Taq polymerase, scientists… we’re working with nature, phew!

Is this a breeding stack or a vector stack?

Amusingly the anti-GM movement has been firing shots (ineffectively) for well over a decade now. Monsanto growth persists year on year. By your definition of winning a war the US is still British owned.

LikeLike

I understand that you need to argue against the claims made by people who are irrationally fearful of all things GMO. While I understand it, it’s not particularly helpful to our current reality in that these crazies aren’t really making much progress politically (the idea of “GMO-free insulin” is a cute jab but hardly has any chance of becoming a legislated reality).

However, those of us who have rational points to be made about the companies behind GMO’s, and the legislation that they lobby for – articles such as this hardly address them, as if they don’t exist. There is no legitimate defense for legislation that would essentially ban (or dangerously hamper) standard consumer protection oversight on GMO companies (proposed by said companies). There is no legitimate defense for proposing legislation that bans the labeling of the ingredients/processes that make up our food- this is a dangerous, not to mention corrupt, precedent (and an obviously slippery slope). These are the things that worry many, including myself. Unfortunately, many people with these legitimate concerns are lumped together with irrational, anti-science people. The effect of this is that we don’t have scientists and otherwise intelligent people standing up against clearly corrupt and dangerous legislation that purposefully reduces oversight and therefore increases risk of future abuse. I truly believe that science writers, such as the author, have the best of intentions. That’s why the loudest voices against legislation that may damage the integrity of GMOs should be the scientific community! Science writers typically frame the debate as science vs irrationality (as we see in this article) instead of saying “how can we make sure this great new technology is used safely and effectively by private corporations?”

While GMOs are a wonderful thing in theory, we must all make sure that there is proper regulation/oversight of companies who make such products to make sure that GMOs are put forth effectively in practice (exactly like what we do for drugs). Not to always resort to the “M” word (Monsanto), but it should worry everyone when Monsanto keeps trying to push forth legislation that effectively stops all government oversight designed to protect the consumers. To use the author’s example of insulin: insulin is obviously a wonderful discovery with important medical uses. That being said, we make sure that the factories/companies that make insulin abide by best practices so that consumers who use the insulin are protected! This important point is almost entirely ignored by the well-meaning pro-GMO scientific voices, because it is so much easier to just argue with the lowest common denominator (irrational science-fearing individuals).

To sum it up, many who are “anti-GMO” can more specifically be described as pro-oversight and pro-consumer protections, and have little to no problem with GMO technology in a vacuum. I’d like to see these two opposing communities united in favor of effective oversight and transparency (labeling).

LikeLike

This post had nothing to do with GMO labeling or dismantling regulations. Are you sure your criticism is appropriate, or do you think you are instead bringing a different issue into this?

LikeLike

Where are your examples?

” when Monsanto keeps trying to push forth legislation…”

Such as? Are you referring to the so-called “Monsanto Protection Act”? If so, have you actually read it?

“that effectively stops all government oversight designed to protect the consumers.”

Protection from what? If it’s not “omg may cause cancer!”, then I’d be interested to know what it really is.

And if this is really your argument, stop pretending to be anti-GMO when you’re really just anti-Monsanto and anti-corporation.

LikeLike

Karl: I am obviously aware that this article didn’t deal with those two things. That is the entire point of my post, I am commenting on the atmosphere of the debate, and on things that should be focused on instead. I would say that, for the most part, it’s really not a criticism that singles out the author.

Brett:

I didn’t think I’d have to post a work cited, but a simple google search yields many results, for example:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/elizabeth-kucinich/monsanto-protection-act_b_3921968.html

Here’s another, from the nytimes:

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/05/us/on-hawaii-a-lonely-quest-for-facts-about-gmos.html?_r=0

“And her bill, like much anti-G.M.O. action, was inspired by distrust of the seed-producing biotechnology companies, which had backed a state measure to prevent local governments from regulating their activity.

That bill, which passed the State Senate but stalled in the House, appeared largely aimed at other Hawaiian islands, which were used by companies like Monsanto, Syngenta and Dow as a nursery for seeds.”

That article specifically points out how biotech corps are trying to get laws passed that prevent regulation. Shouldn’t that worry us?

“Protection from what?” So, by your logic, we don’t need regulation on food and drugs? Obviously it is protection from future, unknown harm. Imagine if an aspirin company decided to say “you know what, we’d really rather you not regulate us. It hurts our bottom line.” We would rightly say “too bad.”

LikeLike

Mike: It is interesting to see what you use as sources. Brett asked if you had read the bill. Your source is Elizabeth Kucinich’s spin-doctored INTERPRETATION of the bill. Only someone looking at it through Organic Consumer’s Association colored glasses could ever come up with this bill being protection for Monsanto. It is clearly and simply protection for FARMERS who have seed in the ground. It protects them from frivolous lawsuits that have nothing to do with safety, just procedural technicalities.

The NYT article by Amy Harmon points out that the anti-GM activists provide lie after lie, and the article shows how one lonely legislator uncovered them for what they were in a methodical way. It says just the opposite of what you are trying to say.

LikeLike

As for your first point, can you please provide some documentation that proves false the huffpost article? I’d rather not just take you on your word.

As for your second point, I was worried that someone would fall into this trap, forcing me to type this out. Yes, the article makes clear that were was a great deal of false information provided by certain activists. I do not dispute this, and I do not defend this, so it’s not a valid point in this discussion. I was referencing that article because it brought to light something very worrisome, that some biotech companies were trying to prevent local governments from regulating their activity. This supports what I was saying (and have been saying). So no, it does not say the opposite of what I was trying to say.

Preventing government regulation is equivalent to saying “trust us”….ugh, forget it, I am not going to spell out with myriad examples why the basic concept of government regulation on food/drugs is a generally good thing.

LikeLike

You could try reading the bill itself, which does not mention Monsanto nor any other agra-corporation and instead is all about the farmers. What it actually says is that some judge somewhere cannot force a farmer to not plant or sell or force him/her to destroy their crops because some anti-GMO activist questions the safety of said crop, even with no evidence to back up that assertion.

Say you’re a farmer planting approved GMO-crops. Some anti-GMO activist comes along and claims the crops present a safety hazard. With no evidence at all to back up that assertion, a judge could force you to stop growing your crops, prevent you from planting them again, and even force you to destroy your current crop that you’ve paid for and invested time, energy, and product into. Now you’re shit out of luck as far as recouping that investment and will continue to be for the duration of the legal challenge. When it’s all said and done, you’re still screwed despite the courts finding that, whoops, there’s no safety hazard. Oh well, sorry about that! And this all in the name of some possible health effects that no one has seen. So this argument actually DOES boil down to questioning the safety of GMO crops that have already been vetted, not simple corporate distrust.

The Farmer Provision Act prevents that scenario from happening. Otherwise you’re only screwing the farmers; Monsanto et all have already been paid for those crops, so why would they care? Well, except that they don’t like to see their customers being put out of business over frivolous lawsuits.

Documentation:

http://www.snopes.com/politics/business/mpa.asp

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Farmer_Assurance_Provision

“So, by your logic, we don’t need regulation on food and drugs? Obviously it is protection from future, unknown harm.”

If that were the case, then all products should be taken off all markets in the name of protection from future, unknown harm. Food and drugs are regulated AND APPROVED because they pass safety testing standards. GMO crops are already plenty regulated. Rallying for useless labels that convey no useful information for the reason “because I really want it!” is not useful regulation and so should be fought against.

LikeLike

I will assume, for the time being, that you are correct in your interpretation of the bill. For some reason, you are mixing together the previous 2 points. The Monsanto act was never mentioned in the 2nd article. The second article furthered my point in the distrust of those offending corporations (not corporate distrust in general, fyi). It simply stated that through some other local legislation, those corporations are attempting to shield themselves from any regulation in Hawaii. So no, my arguement does not simply biol down to the safety of GMO crops. It boils to when specific corporations lobby government to scale back regulation that can often be needed to ensure consumer protection (as it is in nearly all industry).

You are misinterpreting what I meant by “unknown harm.” Let me use an example to best illustrate. There is little to no “unknown harm” in a chicken sandwich. And yet, we make sure to inspect the chicken farms and chicken processing plants (and rightfully so). This is because that while we know that chicken is just fine in theory, we also know that there is a very real risk of food corruption unless we put in the proper oversight (which sometimes happens anyway, unfortunately). Whether it’s malfunctioning equipment, or poor sanitary procedures, etc. Apply this point to this scenario of these specific biotech companies who are doing the aforementioned lobbying. Let’s make sure they aren’t putting forth a contaminated product/process by putting/keeping scientists (FDA and whatnot) on their back. I know you must already agree with this which is why you too should be against such anti-regulation efforts. You say “GMO crops are already plenty regulated” – good! Let’s continue that regulation instead of allowing legislation that may STOP such regulation. This is and continues to be my main point in all of my posts.

As for arguing against transparency…really? The onus is on the company to prove their product to the people, it’s why we have something called marketing (something they have more or less already succeeded at by the way, most Americans already eat GMOs of some kind or another). Instead, they are taking an end run around that by proposing a federal law that would prevent states from setting their own GMO-labeling laws (the Grocery Manufacturers Association is, to be specific). Greater transparency can never, ever hurt consumers, such as you and me. It may nudge biotech companies to make extra efforts to assure and/or educate people, which again, can only be beneficial to the 99.9% of us who don’t own a biotech firm (I suppose that .00001% of us who are major biotech shareholders might lament at (possibly) increasing their marketing budget a bit).

LikeLike

Mike,

From your link, this is what Mrs. Kucinich wrote:

This is what the bill actually said:

Like most legislation it is written in an ambiguous manner to keep lawyers in business. It does not mention any agribusiness companies, but does mention farmers, and applies when requested by farmers. It doesn’t give the USDA any power it doesn’t already have. It just puts into statute what the USDA is already doing.

Explanation from the Wiki article Brett gave:

Note that this says legal challenges to the safety of the crops. The crops have already been determined safe, but someone is challenging the way approval was given. If someone came up with convincing evidence of the crop being unsafe, the USDA could still stop the production, or allow it to be stopped.

As for your linked claim that the agricultural companies are trying to decrease regulation. No, they are trying to avoid the excessive and arbitrary regulations recently passed by individual counties in Hawaii that would essentially stop the companies from doing research there. They are not unregulated. They are already regulated under state and federal law.

LikeLike

Thanks for putting this analysis together. Its the best deconstruction of the claims about the Monsanto Protection Act I have seen to date. I am particularly glad you pointed out that the partial reregulation remedy is precisely what the Supreme Court allowed in the sugar beet case, where the court ruled that a lower court’s injunction was an abuse of discretion. The effect of the provision is not that it gave USDA powers that it didn’t already have, it made it explicit to avoid arguments that USDA didn’t have that authority.

Also, everyone overlooks the last sentence, “nothing in this section shall be construed as limiting the Secretary’s authority under section 411, 412 and 414 of the Plant Protection Act.” Those sections authorize USDA to prohibit plantings of anything shown to be a plant pest. A Court finding that the agency’s procedural evaluation was incomplete is not the same as the court finding that the product is an actual hazard. Successful challenges to deregulation to date have never been decided on evidence or proof of harm, only that the agency’s evaluation did not dot all I`s and cross all t’s. If a courts revoking of deregulation was the result of a showing of actual harm, the court still has the authority to enjoin, and the provision will not interfere with the court’s discretion to do so.

Finally, there is a lot of convoluting what is merely authorities that may be exercised by USDA (authorities the US Supreme Court ruled in the sugar beet case they already have)with tort issues. People often claim that if somehow food from gmo ingredients causes personal injury, or the cultivation of crops with biotech traits causes economic injury, the so called Monsanto protection Act bars suits against biotech companies. I wish someone could explain to me how the provision you pasted above bars tort claims against Monsanto. If this had been its intent, it failed miserably when farmers filed suit against Monsanto for damages due to market disruptions when a biotech wheat was found in an Oregon field. The suit was filed after the Monsanto Protection Act was enacted.

LikeLike

“I am particularly glad you pointed out that the partial reregulation remedy is precisely what the Supreme Court allowed in the sugar beet case, where the court ruled that a lower court’s injunction was an abuse of discretion. The effect of the provision is not that it gave USDA powers that it didn’t already have, it made it explicit to avoid arguments that USDA didn’t have that authority.”

What the opponents to what is characterized incorrectly as the Monsanto Protection Act are essentially misrepresenting that the courts should have no discretion other than total injunction if a court finds the agency’s review process was incomplete. I question whether the legislative branch can constitutionally remove the court’s discretion whether to impose injunction as a remedy. And as was decided in the sugar beet case, the court itself said it had the authority to stop short of total injunction and allowed a partial reregulation remedy that would be consistent with the provision. Note, the court itself, nor the entities bringing suit claiming that the deregulation decision by the agency is in error, raise error on the part of the applicant for deregulation, only error on the part of the agency.

Again, I would reiterate that no overturned deregulation decision to date has hinged on proof or evidence of actual harm from the cultivation or ingestion of deregulated crops with biotech traits. In their petitions for court review of whether the deregulation was granted properly, plaintiffs may indeed raise theories of how harm might occur, but the decision to overturn rests on whether the agency is obligated to, or has properly evaluated these possibilities. A court decision to rescind deregulation does not mean that the court agrees that the plaintiff has proven harm, only that the agency’s evaluation was procedurally incomplete.

LikeLike

Please take a look at our comment policy and consider keeping discussions on-topic. If you want to bring this up as its own topic, you can always start a discussion in the forum. The reason why we have this policy is because otherwise every thread just becomes a rehash of the same stuff, and not about the topic of the post.

LikeLike

Sorry Karl, bringing it up as its own topic on the forum probably would have made more sense, I didn’t think of doing that at the time

LikeLike

And the ice forming protein for ice cream as well.

LikeLike

I didn’t know that! Thanks for sharing!

LikeLike

I’ve always found the distinction pretty obvious actually. I don’t think conflating food and drug GMOs as a single type of thing in the discussion is particularly useful. It falls somewhat, I feel, into the same sort of arguement as “ah but breeding is GMO too, so you oppose breeding!” (as a stand alone, one can, I feel, highlight that breeding introduces unknown changes and use it as an arguement against silly levels of testing for unknowns)

We all (I assume) know that when someone is railing against GMOs that they’re specifically railing against a certain subset of everything that could, by a pedantic explanation, be considered GMO. While I’m generally a fan of pedantry (being a giant pedant myself) I get rather tired of it when used this way.

To counter, however, a point raised above…

Not really. I’ve explained this now ad nauseum, so may skip some bits… but bear with me and someone might provide a link to a larger explanation.

During the insertion process, sure, it is possible that some genetic (or epigenetic even) changes occur in the plant cell being transformed. These will persist within the plant (for sure with genetic, for some unknown time for most epigenetic) so long as it is “bred true”. This, however, is the achilles heel of the arguement about genetic damage. It utterly ignores how the process of commercializing a GMO goes. I’ll lay this out rather simply.

1. Insert gene into plant cell.

2. Grow plant cell up to maturity and propagete, selecting only for offspring with the insert (which will also carry along any genetic damage)

3. Test your plant for efficacy (ie does it kill bugs, does it resist herbicide or such)

4. Decide to commercialize the trait.

5. Introgress the trait into commercially viable lines.

6. ?

7. Profit.

Any unintended genetic changes will persist from 1-4. You’re basically testing the transformant for efficacy. Once you know about efficacy however you’re likely 2-6 years into the process, and you’re likely testing in a non-commercial line anyway (each different line requires different conditions to transform effectively, so it follows that you’ll always lag behind commercial development in terms of what you can and cannot transform) so you need, in order to be succesful, to have the trait in lines which will actually sell. There is no point having an insect resistant corn line that is 8 years behind current elite hybrids, nobody will buy it.

Now, trait introgression is currently precise enough that what you end up with, is your elite line containing only the insert from the transformation line and none of the rest of it. So what this means is that even if transformation altered every single gene in the transformed individual once you introgress into your elite background… not a single genetic change will persist, because none of those genes are there any more.

Thus the arguement that unintended changes may occur is only valid in situations that simply don’t arise. There is no mechanism for this change to persist across a properly executed introgression. There is nothing to fear about changes caused by transformation (insertion) because these changes simply do not exist in the end product. You may therefore put these fears to rest, they come about because very few people know enough about how breeding and biotech go hand in hand, I guess in part because it isn’t very sexy, and not particularly scary either.

LikeLike

Ewan, I think in the case of processed components like sugar or oil from GM plants, the analogy to GM-insulin or GM-rennet is perfectly appropriate. In sugar from beets or corn and oil from corn, beans, cotton, or canola, there is absolutely no DNA or protein in the end product. In the case of insulin and rennet, the risk should be greater if there is any risk at all, because you are isolating an enzyme.

LikeLike

I’d agree with GM rennet. GM insulin is a different beast in that it is something people have to take (well, insulin in general, nobody has to eat corn products or cheese), and isn’t something everyone is exposed to. In my opinion it muddies the water and makes it seem that you are purposefully misunderstanding the concerns of whoever you’re having the discussion with. Sure, there are parallels (as each thing is identical to its non-GM counterpart), I just don’t know how useful they are in the debate.

That said, I’m hardly one to talk about being useful in the debate…

LikeLike

“However, what I am interested in most is if GMO Inside and other anti-GMO groups will realize that the process of producing the GMO ingredients in Cheerios (corn starch and sugar) is identical in principle to the way insulin—and many other drugs, like your dog’s rabies shot—is made.”

The rabies shot that was given to my dog has left her with life threatening epileptic seizures that are close to impossible to control. Each episode she comes close to seizing to death requiring us to have to rush her to animal emerge. Now that I know it is GMO that makes complete sense as to why it did that where years before these shots didn’t leave animals with vaccine injuries. Thanks for pointing that out and clearing up the question that I had.

LikeLike

Rabies vaccines have long had side-effects, before genetic engineering. It’s a notorious disease, and vaccinations have brought far more benefits than harms. People and pets used to die from this, you know. I’m sorry that your dog had side-effects from a rabies vaccine, but it’s not because of genetic engineering.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rabies_vaccine

“In 2005 the WHO Committee on Rabies noted that although the use of Semple vaccine was still widespread, it was responsible for severe and long-term side effects.” This was developed in 1911, long before genetic engineering.

From: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2966399/

LikeLike

brandie: It is difficult to leave your comment unchallenged. In addition to Karl’s response, I would suggest this site: “What is a recombinant vaccine, and how does it work?” http://vetmedicine.about.com/od/vaccinations/f/FAQ_recomvacc.htm

“Advantages of the recombinant vaccine technology are that there is virtually no chance of the host becoming ill from the agent, since it is just a single protein, not the organism itself. Traditional vaccine risks come from the organism not being totally weakened (attenuated) or a reversion to a virulent (disease causing) form. Another advantage of a recombinant vaccine is that it does not need an adjuvant. An adjuvant is an agent that stimulates (irritates) the immune system to find and react to the vaccine agent. Some adjuvants have been implicated in causing cancer in some animals over time.”

The assertion that rabies vaccines in the past used to be risk free and that vaccines from recombinant techniques have somehow inserted an unprecedented risk could not be further from reality. I know from personal experience since when I was a kid in the 1970’s, we had a dog have a severe reaction to a rabies vaccine. If you want to avoid a recombinant vaccine, you can ask your veterinarian, but it would be a mistake to advise others that older vaccines are safer.

LikeLike

There is actually some history of opposition to GM insulin, though we don’t hear about it much these days: http://www.nytimes.com/1989/11/09/business/court-ruling-sets-back-genetic-engineering-in-germany.html

LikeLike

Thanks for the link, Adam!

LikeLike

Can German diabetics use human insulin that’s imported?

LikeLike

Actually, GMO insulin is not quite “life-saving” as you suggest – in fact, insulin derived from the pancreases of abattoir animals (whose genetic structure was actually closer to human insulin than modern insulin receptor ligands [a.k.a. insulin analogues] than the products sold today. However, within days of introduction for rDNA insulin, floods of adverse event reports flooded in from around the world (first from Norway, then the UK, then Switzerland, Germany and the U.S.), most notably because of life-threatening hypoglycemia unawareness. In fact it took the pharmaceutical industry over 15 years before they introduced insulin varieties with any sort of enhanced ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion) characteristics. However, the FDA mandated disclosure of biosynthetic insulin (the label “rDNA origin” is required), whereas consumers of GMO foods get no such disclosure. The real issue is whether transparency should be mandated? Most people believe that is an American entitlement.

LikeLike

Do you have any reputable citations for your claims? Specifically, I find it strange that insulin from pigs would be more bioeffective than human insulin produced in bacteria.

LikeLike

I agree with your claim Anastasia Bodnar. rHuman Insulin has had less problems immune response problems as compared to swine derived insulin. Bovine derived insulin for human use was discontinued in 1998 by FDA and swine in 2006. [Source: FDA [2013] Questions and Answers-Importing Beef and Pig Insulin for Peronal Use. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/QuestionsAnswers/ucm173909.htm

LikeLike

The OP asks:

Sorry, but I agree with Ewan R. This is not a good argument. And please note that I firmly believe that GMO crops are just as safe as non-GMO crops. I don’t at all support the nonsense that constitutes the vast majority of the anti-GMO movement.

That said, there plenty of possible distinctions one can point to between GMO Cheerios and GMO insulin:

* The E. coli that produce GMO insulin are grown in a contained environment. GMO crops are not. So in principle, GMO crops could pose a much greater risk of some “dangerous genetic modification” escaping into the wild and causing widespread problems.

* The final insulin product produced from the GMO E. coli is actually tested for the presence of residual DNA. The same is true for any drug produced from a living source, whether it’s E. coli, yeast, or mammalian cells. I highly doubt such tests are performed on batches of corn starch or sugar produced from GMO crops. So in principle, we wouldn’t know if GMO Cheerios contained detectable modified DNA.

* Drugs produced from GMO cells are actually labeled as such. E.g. Novolin®R Regular, Human Insulin Injection (rDNA origin) USP. That “rDNA origin” means derived using recombinant DNA, i.e. genetically engineered. So diabetics are told in advance that their insulin is from a GMO source. Foods containing ingredients from GMO sources are not required to carry such labels. So in principle, if there was a meaningful risk, the consumer of GMO Cheerios wouldn’t necessarily have the chance to be informed.

Now, in fact, I don’t believe any of these is an actual risk at all. Or at least, not a risk that’s specific to GMOs. Conventionally bred crops are full of genetic modifications that have at least as much potential to be dangerous. It’s silly to think that GMO crops pose some terrible and unique danger, while conventionally bred, non-GMO crops are “natural and safe.” But if that weren’t true, if there really were significant risks that were specific to GMOs, there could easily be strong and rational arguments why GMO insulin was OK but GMO Cheerios were not.

LikeLike

“So in principle, we wouldn’t know if GMO Cheerios contained detectable modified DNA.”

Lets pretend this were true Qetzal, what will your body do with foreign DNA? Considering your DNA is universal [as stated in modern cell theory] and assuming your metabolic system is functional-your body will use these nucleotides [i.e DNA synthesis]. This is no different in how our body metabolizes foreign proteins to isolate amino acids we cannot make [i.e essential]. If we really want to avoid GMO’s, we [humans] would need to revert back to hunting and gathering of wild [non-domesticated] organisms. The science illiterate population may argue that the process of domestication that took place long ago did not result in genetically modified organism but we [the science literate population] understand the facts. People can believe whatever they want but this doesn’t change the facts.

LikeLike

Mario P.,

I tried to be clear that I don’t think any of the things I described represent actual risks. I completely agree that any modified DNA that did end up in the Cheerios would be metabolized. It’s no different than any non-modified DNA that’s (presumably) already in Cheerios, derived from the oats or other grains used to make them.

My point is that someone who DOES believe that modified DNA is a risk can object to GMO Cheerios (where there is no testing for residual modified DNA) yet not object to recombinant insulin (where there IS testing for residual DNA). There’s no logical contradiction there, so the OP’s argument doesn’t really work.

LikeLike

Great article. I assigned my students to read and verify claims made in the article. We had some questions. First of all, why was this article called GMO Cheerios vs. GMO Insulin? GMO’s are organisms, not products of these organisms. Associating these products brings confusion for those who do not understand the role that GE organisms played in producing these molecules [i.e. sugar and insulin]. There are some great post being made my science literate people, this is a breath of fresh air compared to those the science illiterate population who believe their truth becomes fact by just posting their opinions on the internet. Keep the information coming!

LikeLike

Thanks for this blog. I became interested in genetic engineering in the mid-nineties when I was switched from beef/pork insulin to biosynthetic human insulin (BHI). I won’t go into the gruesome details, but after three years my weight had dropped to 88 lbs, I had lost my ability to focus or concentrate and I was unable to be on my own for 24 hours in case I slipped into a hypoglycaemic coma. I began to read about the international outcry among people with Type 1 diabetes who, like me, had terrible reactions to BHI. In a number of countries, including the US and Canada, attempted class action lawsuits had been launched by patients. Eli Lilly was forced to admit that some people had significant problems when they used it’s Humulin insulin products, including an immune response (which I unfortunately also had) it described as “arthralgia/myalgia/arthritis syndrome”. In 2001 I was switched back to pork and beef insulins and the horrible problems I experienced on BHI disappeared – literally.

I think it’s a mistake to assume that people who are using GE drugs are doing well without exception. People with rheumatoid arthritis report very serious side effects such as gum disease linked to Remicade, for example. Drug regulators around the world monitor safety and effectiveness once a drug is approved and on the market. Insulin, which prior to the mid-1980s, was a rather friendly drug is now one of the leading medicines cited in serious adverse drug reactions – that is, reactions to the drug when used as prescribed.

It also is simply wrong to assert that BHI is “chemically identical” to the insulin produced in a healthy body. That, in fact, was a marketing theme in the 1980s by both Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk. The manufactured molecule was inert in the first experiments at Genentech in the late 1970s. They had to unfold the molecule, add a chemical (patented) and refills it. In this way they had a product that reduced blood glucose. However they didn’t test the insulin for any other marker so didn’t know what else it did or didn’t do. Patients who were switched from animal to BHI insulin immediately began reporting very serious problems, including the lack of signals for hypoglycaemia, a potentially life threatening condition. Humulin was submitted to the FDA for approval in May 1982 and within six months it was on the market.

I will never use BHI or the more recent analogues that are now on the market. Ever. It is absolutely essential that proponents of genetic engineering learn more about the experience of people who have used GE drugs instead of repeating the promotional babble of manufacturers.

LikeLike

Sorry but one more important point: in the US diabetic patients are unable to obtain animal-sourced insulin because manufacturers have completely withdrawn all insulin products that aren’t rDNA or analogue products. So it doesn’t make any difference whether patients know they’re using a genetically engineered drug or even whether they are struggling to stay alive while using it. Health Canada has encouraged manufacturers to maintain animal-sourced insulin because, unlike their US counterpart, they recognize that rDNA and analogue insulins are not safe for some people. The same is true in the UK, Australia, etc., and recognized as well by the International Diabetes Federation.

My previous post should have said in the insulin molecule is unfolded, a chemical added, and then refolded.

LikeLike

GMO insulin is already required to be labeled. It says “rDNA Origin” right on the bottle if it is GMO. Cheerios on the other hand are not.

So yes, Cheerios should be held to the same standard as insulin – labeled for consumer information.

LikeLike

Mind blown!

First intense pro vs. con debate on GMO’S

I’ve come across.

Thank you folks!

Bravo. 🙂

LikeLike

Beef and pork insulins were “outlawed” in the USA after 2000. When the difficulties with some diabetics started to occur (roughly 3%-6%) the FDA required the pharmaceutical companies to state so in their leaflets inside the boxes of insulin. as of 2007, diabetics can purchase bovine and porcine insulins from outside the USA, but they must obtain a USDA and FDA permit to import every 6 months. The only manufacture is a British company.

Also, Novo-Nordisk after they had the majority of the world locked into rDNA insulin, went around the world buying up all pork and beef internal organs on long term contracts. Is it not great to live in a free society?????

LikeLike

This is not correct. The products are no longer available in the US due to voluntary withdrawal by the manufacturers. http://www.fda.gov/drugs/resourcesforyou/consumers/questionsanswers/ucm173909.htm

LikeLike

Hello Robert, I am very interested in your statement “Novo-Nordisk… went around the world buying up all pork and beef internal organs on long term contracts.” The company did acquire animal insulin manufacturers (eg., BioBras in Brazil) but I didn’t know about these long term contracts. Do you have a reference I could follow up on? Canada at one time supplied 7% of the world’s pancreatic glands, and NN was very active in the insulin market here in the 1980s. If you could send a reference to me off line that would be great. My email address is colleen_fuller@telus.net. Thanks!

LikeLike

One other thing I should add: the statement “The insulin protein produced via genetic engineering is chemically identical to the insulin protein made in a healthy human body” is incorrect. Manufacturers were rapp d on the knuckles by The Cochrane Group for making this claim, which was designed as a marketing message (especially the bit about “a healthy human body” – almost sounds like a cure). The rDNA molecule is structurally the same, but a chemical is added to influence the kinetics, etc. of the insulin.

LikeLike